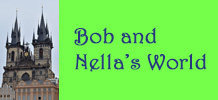

Prague Castle Layout

Prague Castle, as certified by Guinness, is the largest ancient castle in the world, with a

length of 1,870 feet and an average width of 430 feet (that’s about 750,000 square feet). It’s

situated on top of a hill on the west side of the Vltava River and overlooks Prague’s “Little

Quarter”. Its original version was built back in the 9th Century, and it has hosted the

headquarters of kings of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperors, presidents of Czechoslovakia and

(currently) the President of the Czech Republic.

The Presidential Balcony

The Castle is not the defensive fortification it used to be, and the buildings of the

Castle complex have evolved considerably over the centuries, both in style and function.

At present there are government offices, museums, royal palaces (which have both museum

and governmental purposes at various times) and a few different churches. The biggest

and baddest of these churches is the glorious and cavernous St. Vitus Cathedral, which

you no doubt recall from our last post. You might also remember our last post leaving

off with Nella and I eating some awesome Czech hot dogs at an outdoor kiosk/café in a

corner of the Castle’s St. George’s Courtyard, across from the cathedral and next to an

interesting building called the New Provost Residence.

New Provost Residence with Outdoor Café

From the St. Vitus post, you might remember a statue of St. George and a dragon in a

courtyard south of the cathedral, and you might be wondering why that courtyard isn’t

St. George’s Courtyard. That courtyard in fact has a much less interesting name, being

called the “Third Courtyard” (you can probably guess the names of the first two

courtyards we passed through on the way there). This being the case, you might also be

wondering why the courtyard of the hot dog stand isn’t called the “Fourth Courtyard”.

That’s because the St. George Courtyard is named for this building, which faces it:

St. George's Basilica

Nella with St. George's Basilica

St. George’s Basilica is the oldest surviving church at Prague Castle. It was founded in 920

by Duke Vratislaus I of Bohemia. It was not the first church at the castle – an earlier church,

devoted to the Virgin Mary, was founded in the 9th Century (actually before the castle), but it

was destroyed in the 13th Century. Its location overlapped the northern boundary of the

present-day Second Courtyard. Vratislaus died in 921 and was buried in the new basilica. He

was soon joined by his mother, St. Ludmila of Bohemia, who died later in the same year. Tombs

of both can be viewed in the present-day church. In 973, a Benedictine monastery was founded

adjacent to the church. Both the basilica and the monastery have been destroyed and rebuilt a

number of times over the centuries. The church’s Baroque façade dates from the 17th Century,

and its interior retains the Romanesque character established in a rebuild following a fire in

1142.

Inside the Basilica

As you can see from the picture, the Basilica is much smaller and simpler than the St. Vitus

Cathedral from the last page. It has a central nave and two narrow aisles on either side.

Up in the front there is a raised chancel, with a crypt underneath it. To the right off the

chancel, there is a chapel and burial place dedicated to St. Ludmila, which was not open

during our visit. The crypt is the burial place of some of the monastery’s abbesses. The

tomb of Vratislaus I is more accessible, being located off the front end of the south aisle.

Chancel and Apse

Chapel of St. Ludmila

Church from Chancel

The Crypt

Tomb of Vratislaus I of Bohemia (ca. 888-921)

There are a number of artworks scattered around the basilica, but there aren’t a great many of them.

Painting on North Wall - Assumption of the Virgin

Saint with Book

South Aisle

Bob and South Aisle

A small chapel was added to the basilica between 1717 and 1722, devoted to St. John Nepomuk.

St. John is not buried here – his remains are in the St. Vitus Cathedral, in a spectacular

tomb. But there are a couple of nice altarpieces, some well-done figures and a dome with a

beautiful fresco.

Altarpiece, Chapel of St. John Nepomuk

Another Altarpiece, Chapel of St. John Nepomuk

Figures, Chapel of St. John Nepomuk

Dome with Apotheosis of St. John Nepomuk

The chapel, located to the right of the basilica’s main entrance, also has a door of its

own, which we used to exit the basilica, back into St. George’s Courtyard. Looking around

the south side of the church, we found a third door, which dates back to the 16th Century.

This door was not available for use by the general public. Around the back of the basilica,

we had a better look at its two towers, which are named after Adam (south tower) and Eve

(north tower).

South Entrance to Basilica

Basilica from East

Bordering St. George’s Courtyard on the south is the Old Royal Palace. Some form of royal

residence and ceremonial venue has existed in this position since the 12th Century. As with

the rest of the castle, a number of expansions, renovations and rebuilds have happened since

then, and today the palace functions mainly as a tourist attraction. It attracted us, but

unfortunately it was closed during our visit. But fortunately for you, the palace was open

during our 2007 visit to Prague, and at that time we took some pictures that appear below.

The centerpiece of the palace is Vladislav Hall, a gigantic room designed for banquets,

receptions, coronations and other public events. The hall finds itself pressed into service

for major events up to the present day. The room is so large that it has played host to

jousting tournaments, with actual knights on horseback. There’s even a special equestrian

stairway, from which mounted knights can emerge, ready to joust. Adjoining the hall are the

palace’s chapel, called the All Saints’ Church, and the Diet, a sort of Parliament and Throne

Room, from which the laws and royal proclamations for Bohemia would emerge.

Vladislav Hall and Diet, with Nella and Philip (2007)

Nella in Vladislav Hall (2007)

The Diet - Parliament and Throne Room (2007)

All Saints' Chapel (2007)

Southwest of Vladislav Hall are the rooms of the former Bohemian Chancellery, in a

wing perpendicular to the main palace building. In May of 1618, emissaries of the new,

hard-line Catholic Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, appeared with a letter declaring

the lives of some members of the Bohemian assembly to be forfeit. It seems Ferdinand

had refused to allow construction of some Protestant chapels on royal land, and the

Bohemians had complained. Ferdinand dissolved the assembly and sent the letter. Faced

with this less-than-sympathetic reaction, the members of the former assembly took their

anger out on the emissaries, throwing two of them and a secretary out of a Chancellery

window, in an act known as the Third Defenestration of Prague (the first two had been

unrelated revolts against the city council). The fall was about 70 feet, but everyone

survived. They returned to Ferdinand with the news, Ferdinand raised an army, and the

Thirty Years’ War was underway (more than 8 million would die, and Bohemia would end up

on the losing side).

The Defenestration of Prague (1618)

The Chancellery

Bob in Chancellery (2007)

East of the Royal Palace, across from St. George’s Basilica and forming the south side of

Jiřská Street and the castle is another palace, called the Rosenberg Palace. This palace was

built in the 16th Century by the Rosenberg family, who had to sell it to Holy Roman Emperor

Rudolf II in 1600 to settle debts. In 1755, Empress Maria Theresa created the Theresian

Institution of Noble Ladies, an institution that provided assistance and education for young,

unmarried Austrian and Hungarian noblewomen who were financially down on their luck. After a

suitable renovation, Rosenberg Palace opened in 1756 as the primary facility for this

organization, under the leadership of Archduchess Maria Anna, one of Maria Theresa’s

daughters (she had eleven). This arrangement lasted until 1919, when the aristocracy ceased

to exist and Czechoslovakia became an independent country. The palace was used by the

Ministry of the Interior for several decades, but is now used as offices for the castle

administration and for the Czech presidency.

Entrance to Rosenberg Palace

Jiřská Street, the exit from St. George’s Courtyard to the east, is the main thoroughfare

for the eastern half of the castle, extending all the way to the eastern castle exit.

But if you take a jog to the left part way to the exit, you will end up on a

narrow parallel street known as Golden Lane. The street is picturesque, but not

particularly golden. There are several houses on the north side of the lane, painted in

pastel colors, where people of various trades lived until World War II. One such person

was the author Franz Kafka, who lived in house number 22 for a few months between 1916

and 1917. The street gets its name from the fact that a number of goldsmiths lived and

practiced there at one time. In the present day, the houses have mostly become shops,

though some have been restored to show what they were like when people lived in them.

Heading for Golden Lane Along Jiřská Street

Golden Lane

Goldsmith's Workshop

Herbalist's House

Bedroom/Sewing Room

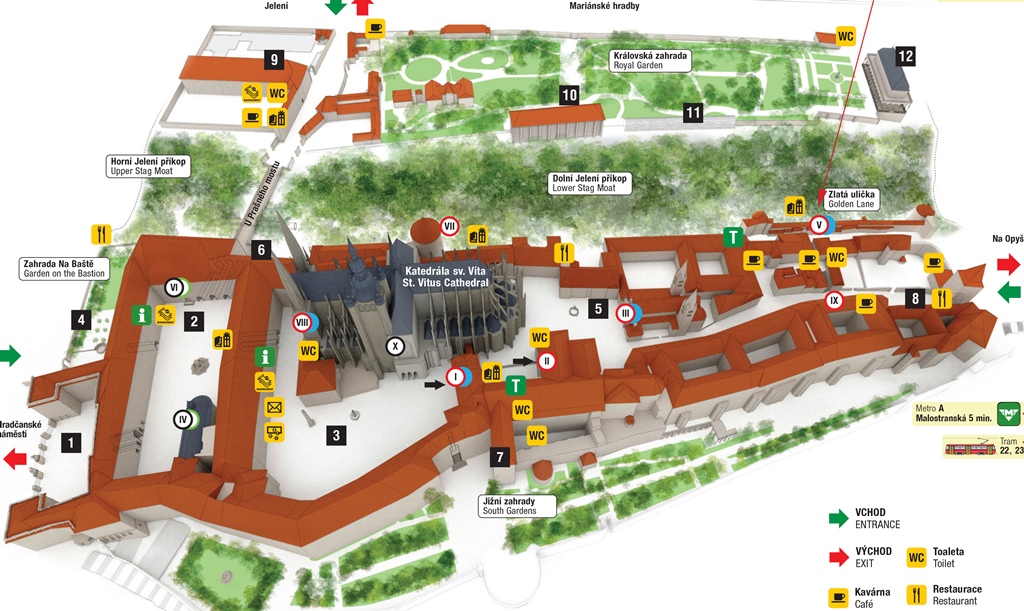

At one point there is a stairway up to an armor museum that extends much of the length

of the lane, with a nice view out the back from the top of the castle’s north wall.

The museum is quite narrow, but has some interesting armor on display.

Bob with Armor

Armor

Reptilian Armor

Armor and Chain Mail

Armor

Weaponry

Chain Mail

Armor with Crown (Kill Me!)

Helmets

Helmet with Fearsome (Fearful?) Face

More Helmets

Helmet with Wings

At the east end of Golden Lane and to the left is a round tower known as Daliborka Tower.

This tower was built in 1496 as a prison, a purpose it served until the end of the 18th

Century. It received its name from its first prisoner, the nobleman Dalibor of Kozojed.

Dalibor was imprisoned for harboring escaped serfs after an uprising, which was a capital

crime. According to legend, Dalibor learned to play the violin while imprisoned and became

very popular with the passersby. But this wasn’t enough to reverse his sentence, and the

music ended when he was executed in March of 1498. The Czech composer Bedřich Smetana

wrote an opera based on this legend in 1866-67. The tower today has become a museum, but

not one of music or of Dalibor, but instead a museum of torture.

Torture Implements, Daliborka Tower

Torture Apparatus

Prisoner Cage

"Rack"

From the tower we headed over to the castle’s eastern exit, where there was an overlook

with a fine view of much of Prague. It was possible to see all the way from the next hill

to the south, Petřín Hill (this hill has an observation tower that looks something like a

miniature Eiffel Tower), to the closest bridge over the Vltava, the Mánes Bridge. In

between were the Old Town (across the river) and the Little Quarter (at the foot of the

castle’s hill).

Little Quarter and Petřín Hill from Castle

Observation Tower, Petřín Hill

View of Little Quarter from Castle

River with Legií Bridge and National Theatre

Mánes Bridge and Old Town from Castle

When we were done with the view, we exited the castle and started down the long stairway back

to Little Quarter level.

Descending from Castle

Near the bottom of the stairs we found a Metro station. We boarded a train and returned to

our hotel. We spent the rest of the day doing a little bit of exploration around Wenceslas

Square (some of this will appear in a future page), but mostly we hung out in the hotel room.

Again, we had ambitious plans for the following day. We decided we would start out at Old

Town Square.