Old Town Square

Prague's Old Town Square (Staroměstské Náměstí; staré=old, město=city or

town, náměstí=square), as you may have insightfully guessed, is the picturesque main

square of a portion of Prague known as the Old Town. The boundaries of the Old Town are quite

specific, as they are defined by the Vltava River and streets which replaced a moat outside a

city wall which existed in medieval times. In 1348, Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV founded the

New Town, to the south of the Old Town, and the Old Town’s wall and moat were dismantled as a

result.

Located within the Old Town boundaries but considered a quarter of its own is the Jewish

Quarter, known as Josefov. Jews have been present in Prague since at least the 10th

Century, and by the 12th Century they were concentrated within a semi-autonomous walled ghetto

in the area of the present-day Josefov. Over the centuries they suffered from pogroms while

sometimes enjoying periods of relative prosperity. In the early 18th Century, more Jews lived

in Prague than in any other place in the world, but later in the century, Empress Maria

Theresa ordered their expulsion. But this was followed by the 1782 Edict of Tolerance from

Maria Theresa’s son, Emperor Joseph II (after whom Josefov is named). This edict extended

many new rights to the Jewish population, while retaining some old restrictions and creating

some new ones. The ghetto itself was abolished in 1848, and the quarter was extensively

rebuilt between 1893 and 1913 as part of a modernization initiative.

As Prague was taken over by Nazis early in World War II (before the war actually started, in

fact), its Jewish population felt the full impact of the Holocaust. Of the nearly 40,000 Jews

in Prague in late 1941, only about 7,500 survived. Oddly, Adolf Hitler ordered that certain

Jewish historical landmarks (some synagogues and an old cemetery) not be disturbed. His

intention was to preserve the area as a museum to an extinguished race. In 1942, the ruthless

Nazi officer in charge of Jewish deportations and other atrocities and known as the “Butcher

of Prague”, SS General Reinhard Heydrich, was assassinated in a daring raid. The Nazis

responded by capturing or executing everyone involved in the plot (and many who were not) and

annihilating the villages of Lidice (340 people) and Ležáky (44 people). After the war, some

Jews who had emigrated prior to the war returned to Prague and some of the survivors left,

many ending up in the new country of Israel. Others emigrated during the years of Soviet

occupation, and today there is only a Jewish community of about 2,000 in Prague (it’s thought

there are probably about another 8,000 Jews in the city who don’t register as such).

Historical sites remaining in Josefov include six synagogues (the oldest dating back to the

13th Century), a Jewish Town Hall and Ceremonial Hall, and an Old Jewish Cemetery. The

cemetery was in use from the early 15th Century until the late 18th Century. Far more people

are buried in the cemetery than would normally fit in such a small area, as for much of its

period of use, expansion was forbidden. This problem was addressed by adding new layers of earth

on top of the old ones, thereby growing the cemetery vertically. Some of the burial plots

have been stacked as many as twelve deep, and the level of the cemetery is well above that of

the surrounding streets (the boundary walls also act as retaining walls). As each layer was

added, gravestones from the lower levels were moved to the top of the new layer, so there is

an extreme profusion of Hebrew-inscribed gravestones. We didn’t get a chance to visit the

Jewish Quarter, but here are a couple of pictures from the Internet:

Old Jewish Cemetery

Old-New Synagogue

We did have a good look at Old Town Square, though. It was actually a pretty short walk

northward from our hotel at the foot of Wenceslas Square. On the way, at a cross-street called

Havelská, we noticed an open-air street market, called the Havelské Tržiště Market.

This market dates back to 1232 and is open daily. A great deal of attractive produce, plus

various souvenir objects, are available there.

Havelské Tržište Street Market

Havelské Tržište Market (1888)

Continuing up the street, we soon reached the Old Town Square, entering near the Old Town Hall.

The Old Town Hall began life as the Old Town Hall with the purchase and renovation of a large

house in 1338. Over the years and centuries, the hall was expanded through the purchase of

adjacent houses and the construction of add-ons, such as a clock tower in 1364. From the

outside, the hall still looks like multiple houses whose architectures aren’t necessarily

compatible with each other. Possibly the most unique house to be incorporated in this way is

the Dům U Minuty, or Minute House, a 15th Century house which is covered with scenes

from the Bible and from myths and legends. The writer Franz Kafka lived in this house with

his parents from 1889 until 1896, at which time it was purchased and incorporated into the

Town Hall. Northern and eastern extensions to the hall were unfortunately destroyed by fire

in the final days of World War II, during the fight by the Czech Resistance and the Red Army

to expel the Germans from Prague.

Old Town Hall with Astronomical Clock

Dům U Minuty House

For centuries the Old Town Hall was the center of the municipal government, and announcements

or public displays were frequently performed in its vicinity. One such display took place in

1621, following the Bohemian loss at the Battle of White Mountain, at which time forces of the

Holy Roman Empire publicly executed 27 leaders of the Bohemian uprising. To this day there are

27 white crosses on the pavement, in tribute to those executed. The executions inspired other

rulers to take up arms against the Holy Roman Empire and its allies, in what became the Thirty

Years’ War.

Executions at Old Town Hall, 1621

Tribute Crosses

Probably the most interesting feature of the Old Town Hall is its astronomical clock, also known

as the Orloj. There are a number of astronomical clocks scattered around Europe and around

the world, and Prague’s is the third-oldest, having been installed in 1410. But the Prague Orloj

still functions, making it the oldest operational astronomical clock in the world. The Orloj has

two clock faces. The lower face is the Calendar face, which keeps track of the current day.

There is an outer ring which is populated with the names of 365 saints, and there is a pointer

which always points to the saint representing the current day. Inside the outer ring are twelve

painted “medallions” which represent the months, depicting agricultural tasks which normally take

place during each month. Inside the month medallions are twelve smaller medallions with the signs

of the zodiac. On either side of the Calendar face there are two pairs of statues – on the left

there are a philosopher and the archangel Michael, and on the right there are an astronomer and a

chronicler.

Astronomical Clock

Calendar Face

Calendar Face Detail

Philosopher and Archangel Michael

Astronomer and Chronicler

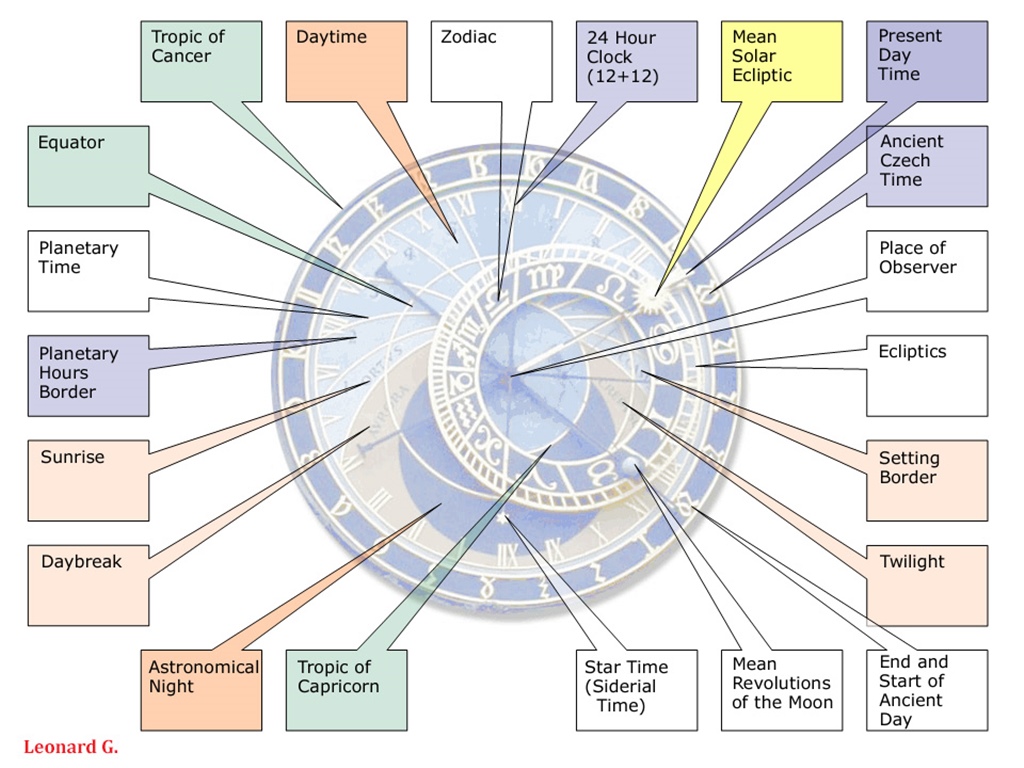

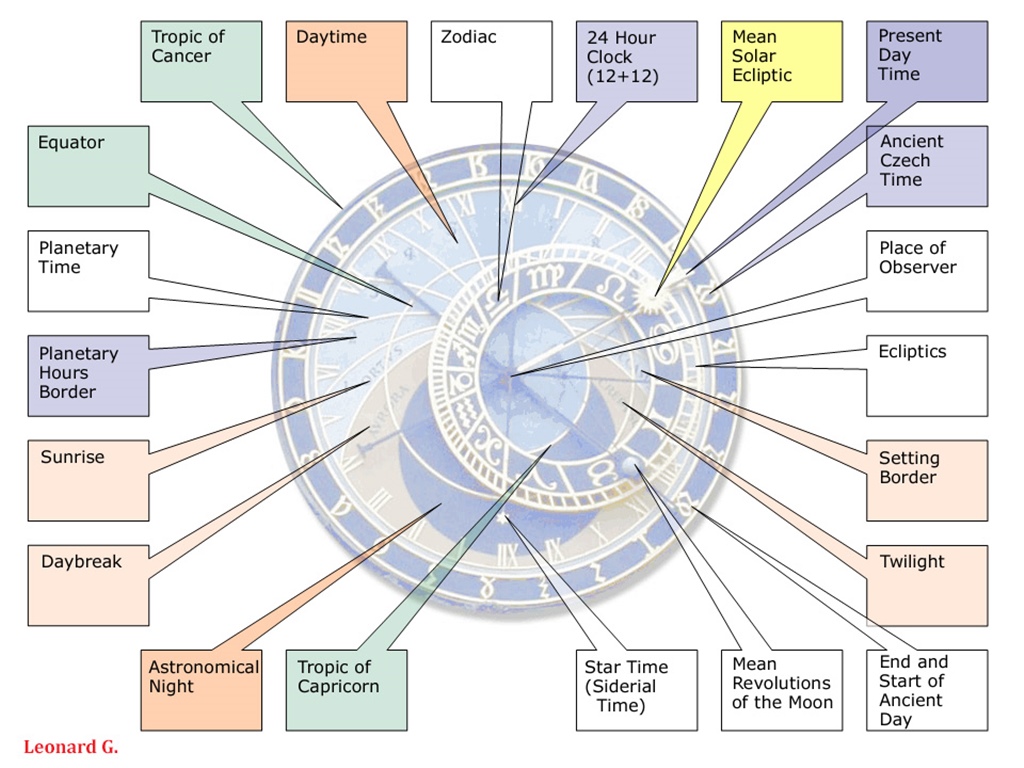

The Astronomical face, above the Calendar face, is more complicated. Some of the information

displayed includes current time in Central European Time, current time in Ancient Czech Time

(hours between sunrise and sunset are divided into 12 equal “hours”), sidereal time, the

location of the Sun on the ecliptic, the position of the vernal equinox, the sign of the zodiac,

the time of sunrise and sunset, the position of the moon on the ecliptic, and the phase of the

moon. There are two pairs of figures surrounding the Astronomical face also. These figures

represent Death (a gold skeleton) and three allegorical sins – on the left there are Vanity and

Greed, and on the right, next to Death, is Lust (or earthly pleasures, to be more generic).

Astronomical Face, Apostle Windows and Deadly Sins

Functions of Astronomical Clock

And every hour, the clock puts on a show, and there is always a crowd gathered to watch it.

First, the Death figure rings a bell (“It’s time!”), and the sin figures start shaking their

heads (“not yet!”). Two windows above the Astronomical face open, and figures of the twelve

Apostles take turns appearing in them. It’s not exactly the Folies Bergère, but in 1410,

Czechs had to take their entertainment where they could find it.

Astronomical Clock

After the clock show, we walked out into the square and looked at the Old Town Hall from

different angles.

Main Entrance to Old Town Hall (15th C.)

Old Town Hall with Astronomical Clock and Entrance to Tower

Old Town Hall Detail

Old Town Hall

Bob in Old Town Square

In the square itself, there is a large monument to Jan Hus. You may remember from the Prague

introductory page that Jan Hus was a Prague preacher and linguist who was sort of a Protestant

who pre-dated Martin Luther by 100 years. He criticized the Roman Catholic Church for some of

its practices and advocated certain reforms, and for his trouble he was burned at the stake in

Germany in 1415. Hus had been very popular in Prague, and his treatment at the hands of the

Catholics caused the city to become staunchly Hussite and later Protestant, until they were

forcibly converted back to Catholicism by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1620, during the Thirty

Years’ War. Prague remains generally Catholic, but Hus is still considered a national hero.

The monument was built in 1915.

Jan Hus Memorial

One thing we didn't see was the Marian Column, a monument with the Virgin Mary at

its summit which was built in 1650. When Austria-Hungary was dissolved in 1918, the column

was knocked over and demolished by a crowd that felt it was a symbol of Catholicism and

Habsburg domination. We did see a brass strip in the pavement known as the Prague Meridian,

however, which was positioned so the shadow of the Marian Column would fall upon it at high

noon every day.

Marian Column (ca. 1900)

Toppled Column (1918)

The Prague Meridian

Since 1918, memories of Habsburgs have faded and the population has become less interested in

Christianity in general. As a result, people no longer found the column (or the idea of the

column) to be offensive. In January of 2020, a few years after our visit, it was decided that

the column would be reconstructed, and the construction was completed on June 4, 2020. So now

the people of Prague can tell what time it is again.

Rebuilt Column (2020)

There are several interesting buildings surrounding Old Town Square. Prague didn’t suffer as

much bomb damage as many European cities during World War II, so many pre-war buildings have

survived intact. In particular, many buildings in the art nouveau style popular around the

turn of the century can be found. One such building, just north of the Jan Hus monument, was

built for the Prague City Insurance Company, and was completed in 1901 (three Baroque houses

were demolished at the time to make room for it). Some of the sculptures on the façade of

this building were done by the workshop of Ladislav Šaloun, who was the designer of the Jan

Hus monument. The building currently houses the Ministry of Regional Development.

Bob and Prague City Insurance Company

Opposite this building, on the south side of the square, is a house called Storch’s House,

notable for the elaborate paintings on its façade. The building dates back to the 15th Century,

but it was heavily renovated (including the addition of the façade paintings) in neo-Renaissance

style by its owner, a bookseller named Alexandr Storch, in the late 19th Century. Among other

things, the paintings depict St. Wenceslas on horseback and the Three Kings.

Storch's House

Between these two buildings, just east of the Hus monument, is a rococo confection of a

building called the Kinský Palace. This isn’t any kind of rococo revival style – the

building was built for Count Jan Arnošt Golz between 1755 and 1765, when rococo was in

vogue, and its façade has not been renovated. The palace was sold to Prince Rudolf Kinský

in 1768, explaining its name. Again, there is a connection with Franz Kafka: Kafka

attended a grammar school in the building between 1893 and 1901, and his father Hermann

ran a haberdashery on the palace’s ground floor. In 1948, the coup d'état

establishing Czechoslovakia’s Communist government was announced from the balcony of this

building. Beginning in 1949, the palace has been administered by the National Gallery,

and it is currently in use as a museum for part of their collection.

Kinský Palace/National Gallery

Kinský Palace/National Gallery

Also located around the square are two notable churches. One of them, located to the east of

the square, is called the Church of Our Lady Before Týn. This church is the most prominent

landmark visible from the square, and one of the most prominent landmarks in the city. The

church has two 260-foot towers, each with a central spire surrounded by eight additional spires.

It gets its name from an enclosure, or týn, located behind it. The enclosure was once

used as a guarded area where merchants visiting the city could safely store their merchandise.

The church was built beginning in the 14th Century on a spot that had been occupied by smaller

churches since the 11th Century. Construction was completed in the early 15th Century, except

for the towers, which were completed in 1511. In 1679 a lightning strike started a fire which

badly damaged the main vault, which was rebuilt in a Baroque style.

Church of Our Lady before Týn (1865)

Church of Our Lady before Týn

The affiliation of the Týn Church mirrored the religious turmoil that characterizes Prague’s

history. The church (and its predecessors) began as a Catholic church, but shortly after

the execution of Jan Hus in 1415, it became a Hussite church. After a couple of turbulent

centuries and a defenestration, the Catholic forces of the Holy Roman Empire defeated the

Bohemians at the Battle of White Mountain, and the Týn Church again became a Catholic church,

in 1621. In addition to executing 27 rebel leaders, the victorious forces exhumed some of

the former leaders of the Hussite Týn Church, who had been buried in the church, and burned

their remains. On the façade of the church, a gable between the two towers displayed a

golden chalice (actually made of gilded copper) which was a symbol of the Hussites. The

Catholics removed the chalice, melted it down, and used the metal to replace the chalice with

a sort of medallion of the Virgin and Child, which appears on the gable to this day. But in

the more secular age of 2017 (a year after our visit), it was decided to restore the chalice,

a new version of which now appears in a niche below the medallion.

Gable with Medallion, Chalice and Marian Column (2020)

Finding the way into the Týn Church isn’t that straightforward. You may have noticed from

the pictures that the church is set back from the square, with other buildings in between.

An archway in one of these buildings leads to a walkway which takes you to the church

entrance. After some searching around, we found our way into the church. The inside was

beautiful, but photography wasn’t allowed. As a result, we only got a couple of photos, but

we found some on the Internet, apparently taken by someone even less obedient than us.

Inside the Church of Our Lady before Týn

Main Altar, Church of Our Lady before Týn

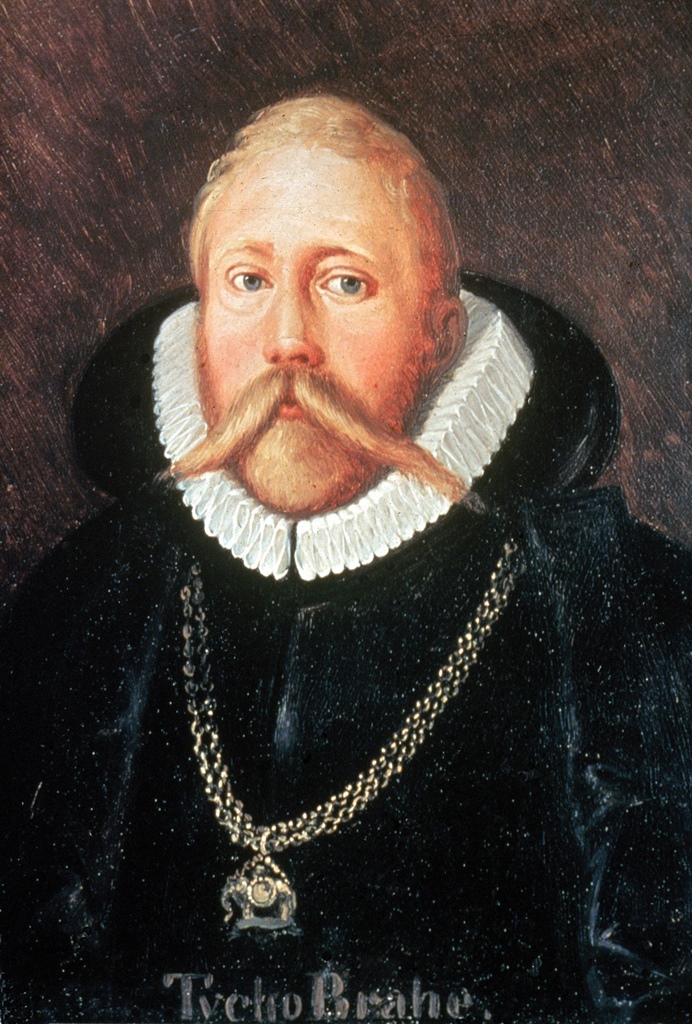

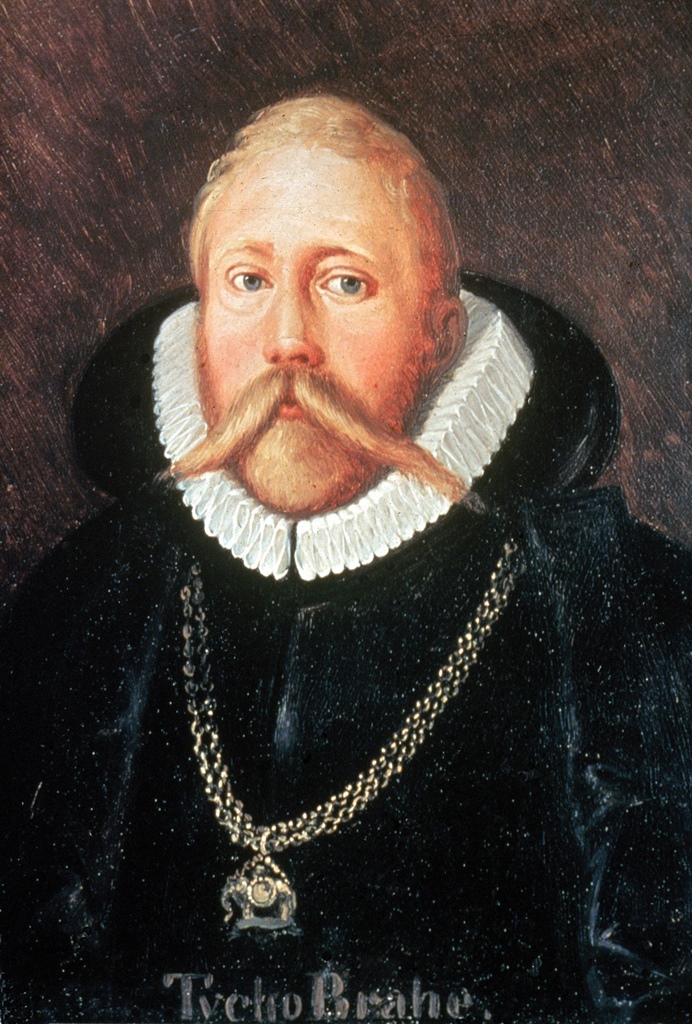

Several locals are buried in the church, and their grave markers are everywhere. The most

famous grave probably belongs to the well-known Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who died in

Prague in 1601.

Grave of Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe

Tycho’s grave was actually opened fairly recently, in 2010, to resolve some burning questions

about Tycho. Tycho Brahe was one of the last pre-telescope astronomers, but his exacting

observations of the sky still led him to challenge many long-held astronomical beliefs. He

benefited from the sponsorship of the Danish king, Frederick II, to perform astronomical and

astrological services, but when the king died in 1588, his heir, Christian IV, was only 11

years old, and rule was passed to a regency council. Tycho had disagreements with the

council, and Christian grew up to be less interested in his work than his father was, and

Tycho ended up being exiled from Denmark in 1597. After a couple of years in Germany, Tycho

obtained the sponsorship of Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor, and moved to Prague in 1599

to build a new observatory. After moving to Prague, he met another astronomer who became his

assistant, named Johannes Kepler. Kepler would go on to become an astronomical superstar in

his own right, formulating three basic laws of planetary motion that transformed astronomy,

partly using observations made by Brahe. But not until after Brahe’s death in 1601.

Monument to Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler

So what are the burning questions that necessitated Tycho’s exhumation in 2010? The first

one goes back to his school days and a drunken swordfight he had with a classmate over who was

the superior mathematician. Both combatants survived the altercation and eventually settled

their differences amicably, but during the fight Tycho lost a piece of his nose. This led to

him having to wear a prosthetic nose for the rest of his life (painted as a normal nose in the

portrait above), and to question number one: accounts from the time described the nose as

being made of gold or silver. Which was it? (Skeletal residue showed it to have been made of

brass. Maybe he had dress noses for special occasions.) The second question is related to

Tycho’s excessively good manners. In October of 1601, Brahe was attending a banquet when

nature began to call. According to Kepler, Tycho refused to leave the banquet to relieve

himself, as this would have been impolite, and he ended up with a burst bladder, which

resulted in his death eleven days later. In recent years, people with too much time on their

hands came up with a plausible theory that Tycho had had an affair with the mother of

Christian IV, and Christian had arranged to have Tycho poisoned, and in 2010, enquiring minds

wanted to know if this was so. (No.) Tycho was returned to his grave after a few days and is

presumably resting in peace, at least for the time being.

Across Old Town Square from the Týn Church, just off the square’s northwest corner, is another

church, the St. Nicholas Church. If this sounds familiar, it might be because there is

another St. Nicholas Church on the other side of the river in the Little Quarter, which was

discussed a few pages ago (there is actually a third St. Nicholas Church to the south, but we

didn’t visit that one). Like the Little Quarter church, this St. Nicholas Church is Baroque

in style, though not to the same overwhelming degree. It was built between 1732 and 1737, on

the same spot as a previous St. Nicholas Church that had been burnt down by invading

Frenchmen. This church is smaller than the one across the river as its builders had a smaller

lot to work with. When the church was first completed, it must have been difficult to get a

good look at its façade, as a large house occupied the space directly in front of it, where

there is now a small park (the house was demolished in 1901).

Jan Hus Memorial and St. Nicholas Church

St. Nicholas Church (Old Town)

St. Nicholas Church (Old Town)

The inside of the church is largely impressive for its height, which is highly decorated

with frescoes and sculpture, plus an impressive chandelier. In the 1780’s, a Benedictine

monastery associated with the church was dissolved by Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, and

the church became Russian Orthodox in 1870. Late in the century, the Russian Tsar Nicholas

II donated the chandelier. In 1920, after the first World War, the church became a Hussite

church and remains so today.

Inside the Church

Chandelier

Dome and Chandelier

Above Main Altar

Main Altar

From the St. Nicholas Church, we headed back across the square and beyond to another Baroque

church, located behind the Týn Church. This was the Basilica of St. James.