Prague Castle, with St. Vitus Cathedral

The St. Vitus Cathedral is the most visible and iconic structure in western Prague. At 337

feet tall and 407 feet long, it's the most prominent structure within the confines of Prague

Castle, which is the largest ancient castle complex in the world, according to the Guinness Book

of World Records. There will be more on the castle in the next page, but for now you can just

think of it as an enclosed collection of buildings on top of a hill overlooking the Vltava River

from the west.

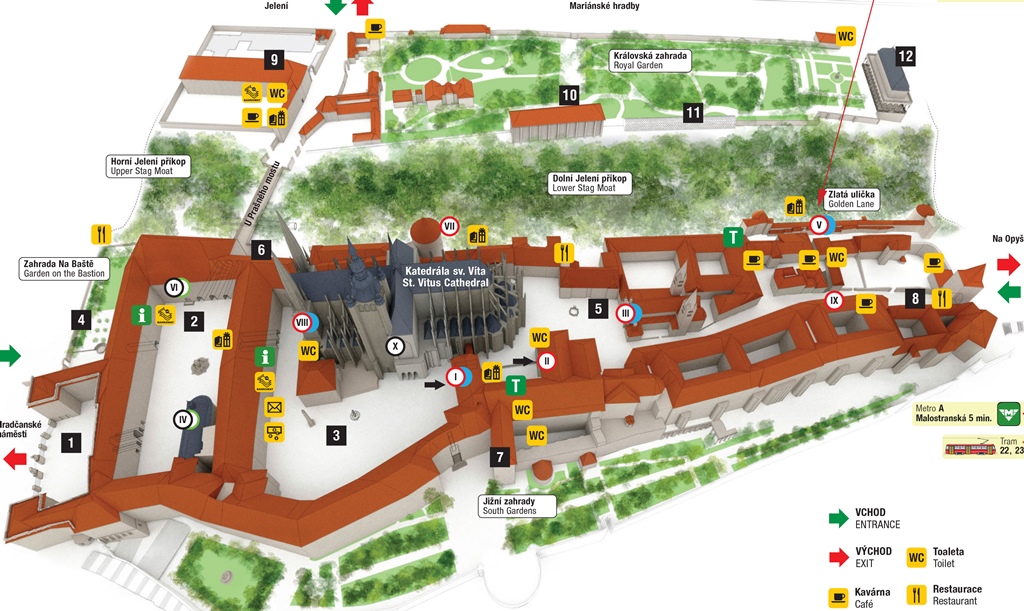

Prague Castle Layout

The present-day cathedral is the third church devoted to St. Vitus that has been built at its

location. Vitus was a Sicilian Christian who was martyred as a teen-ager in the year 303. You

may have heard of an affliction known as St. Vitus' Dance, whose official name is Sydenham's chorea.

The affliction sometimes occurs in rheumatic fever patients, and is characterized by rapid,

uncontrolled jerking movements of the face, hands and feet. St. Vitus is not known to have been

much of a dancer, but apparently someone saw a connection between the condition's movements and

those of dancing celebrants of the feast of St. Vitus. In any case, St. Vitus is now the patron

saint of actors, comedians, dancers and epileptics, and has an illness named after him.

St. Vitus (1493 drawing)

Vitus may have been one of the more obscure saints at one time, but his popularity in Prague

increased greatly in the year 925, when King Henry I of Germany presented bones from the saint's

hand as a gift to the Duke of Bohemia, Wenceslas I. From the Prague introductory page, you

might remember Wenceslas as the "Good King Wenceslas" from the Christmas carol. You might also

remember that he ended up assassinated by his brother in 935, and eventually became a saint in

his own right. But before all that, he built the first St. Vitus church in Prague Castle, a

relatively small Romanesque building for celebration of the saint and a home for his hand bones.

And though Wenceslas didn't know it, he would end up buried there also.

Wenceslas I

The small church soon proved to be too small for those wishing to attend services, and in 1060,

using as pretext the elevation of Prague to a bishopric, construction was begun on a much

larger church, which would become a Romanesque basilica. This was fine until 1344, when Prague

was elevated again, this time to an archbishopric. The Bohemian king at the time, known as

John the Blind, laid a foundation stone for a new cathedral, but was not able to oversee much

construction work, as he died in 1346. He was succeeded by his son, Charles IV, who would also

become Holy Roman Emperor. Charles had ambitious plans for the new cathedral (as well as for

Prague in general), and hired designers and builders who would construct the cathedral in the

French Gothic style.

Charles IV

Construction proceeded slowly because of competing projects, and work pretty much stopped in

the first part of the 15th Century, when the Hussite Wars started. The cathedral was about half

built at this point, and work over the next few centuries consisted mainly of repairs (there was

a fire in 1541) and occasional addition of decorative elements. Finally, in the 19th Century,

funds and determination became available, and work was resumed, with late 19th and early 20th

Century styles being applied to the church. By this time one of the styles in vogue was

neo-Gothic, which went fairly well with the old style, which was Gothic Gothic. Two neo-Gothic

towers were added at the end of the newly completed nave (there were some complaints that the

towers altered the skyline everyone was used to, but the complainers eventually gave up or died),

and construction was declared to be complete in 1929, 585 years after it began. Here's a picture

of how the footprint of the new cathedral (in blue) compares with those of the previous St. Vitus

churches:

St. Vitus Footprints

With the castle being on top of a hill, getting to it from the St. Nicholas Church involved

a bit of a climb. We'd have taken a funicular or an escalator if either was in evidence,

but neither conveyance appeared to exist. A sign pointed the way between some buildings, and

that's where we found stairs. Rather a lot of them.

Stairs to Castle

We're Almost There

At the top we found a large square, called Hradčany Square (Hradčanské Náměstí – a

náměstí is a square, and hrad means "castle"). There are some buildings of note

on this square. One is the Archbishop's Palace, which has been the seat of the Catholic Church

in Prague since 1562 (it underwent a Baroque rebuild in the 18th Century). Another is the

Schwarzenberg Palace, built in the 16th Century in Renaissance style. This palace is now owned

by the National Gallery in Prague, and is used for exhibition of its collection of works by old

masters.

Archbishop's Palace

Schwarzenberg Palace

Schwarzenberg Palace Courtyard

The structure of most interest to us on Hradčany Square, though, was the entrance gate to

Prague Castle (Pražský Hrad), known as the Giants' Gate. The name comes from the statues

of wrestling Titans (1902 copies of 1770 originals) to be found at the gate. Also impressive

(smaller but potentially more lethal) are the two armed soldiers which guard the entrance.

There is an hourly changing of the guard ceremony (we came a little too late for one of them),

including one at noon with a cast of thousands. Or dozens, anyway.

Entrance to Prague Castle

Entrance Gate

Statue of Wrestling Titans

Beyond the gate is a large but empty courtyard, surrounded by buildings which are used by

the government. An archway through one of the buildings leads to another courtyard with a

fountain from 1686. The ticket office is in this courtyard.

Bob and Fountain (Jeroným Kohl, 1686)

Another archway leads from this courtyard into the interesting part of the castle. Your

interest is immediately demanded by the St. Vitus Cathedral, whose two 269-foot neo-Gothic

towers await just beyond the archway. The entrance and exit doors are found at the foot of

these towers, but to get in, you need to join the queue, found along the left side of the

church.

Western Façade, St. Vitus Cathedral

Center Doorway

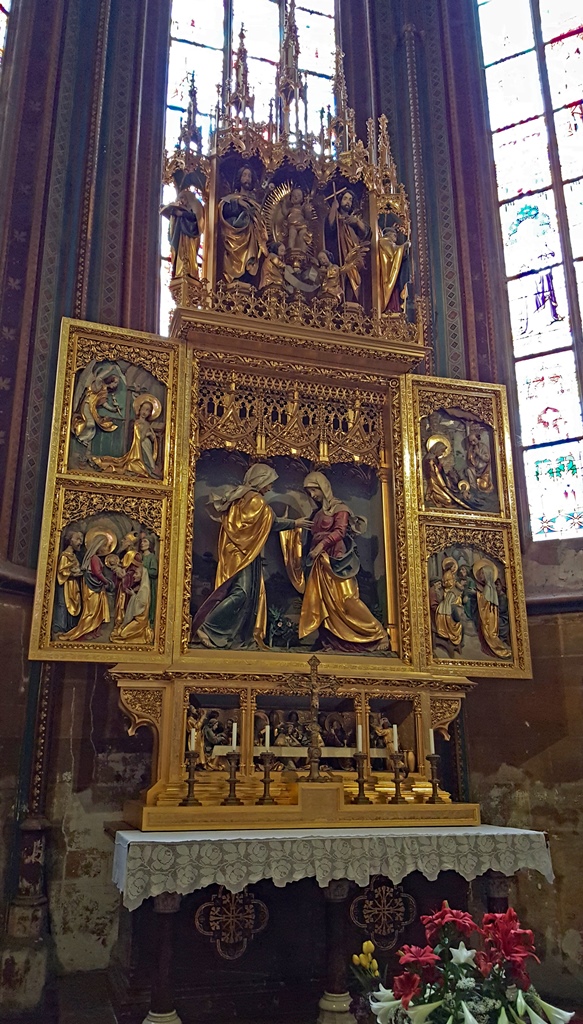

On entering, you find a church that's very big and very Gothic (and very crowded, at least

during our visit). The church has all of the elements required for a cathedral, but many are

done in unique ways. The older elements, which incorporate sculptural concepts, are mainly

the work of Peter Parler, who became master builder in 1352 at the age of 23, and of his sons

Wenzel and Johannes.

Center Nave

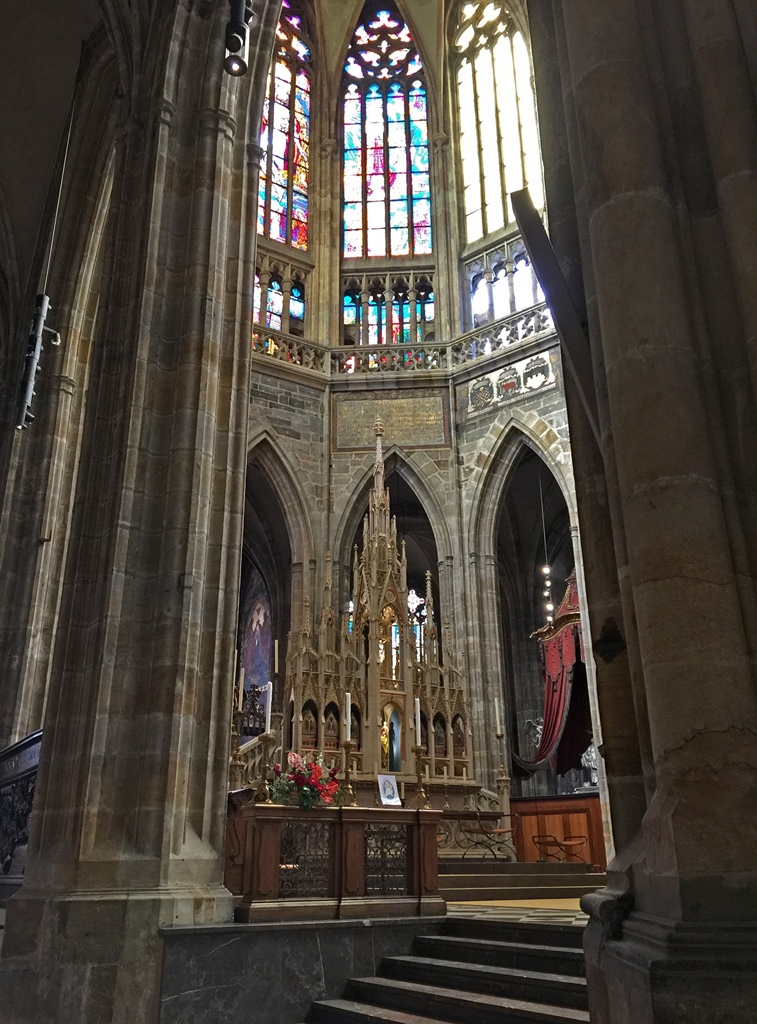

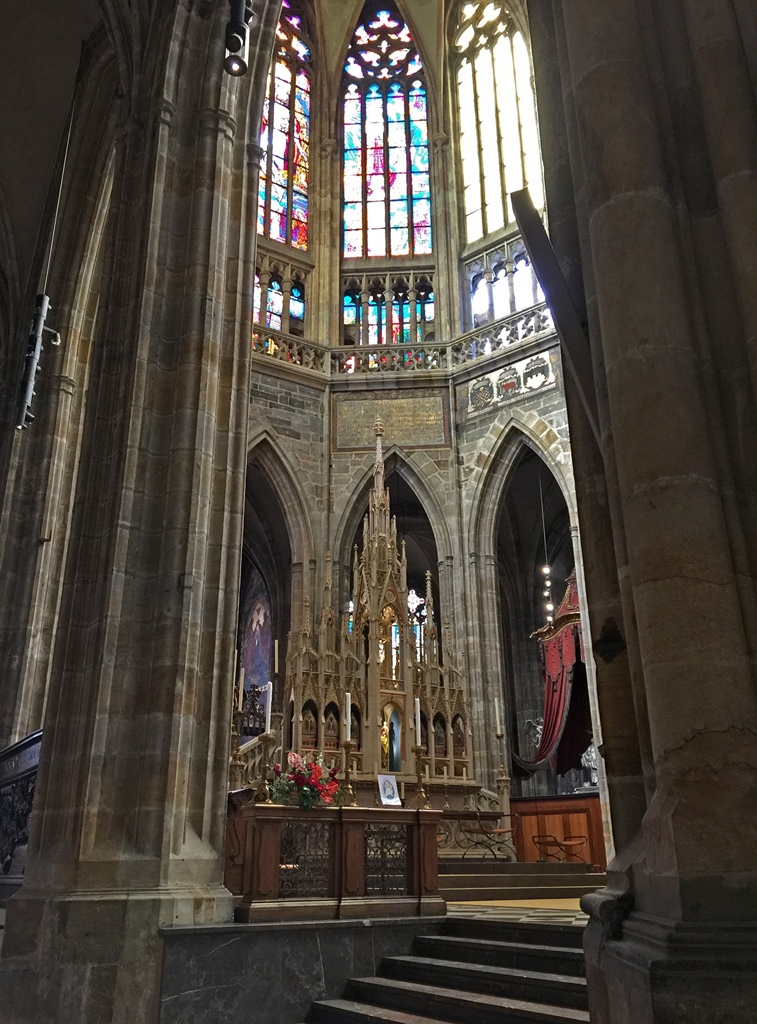

Royal Mausoleum and Eastern Window

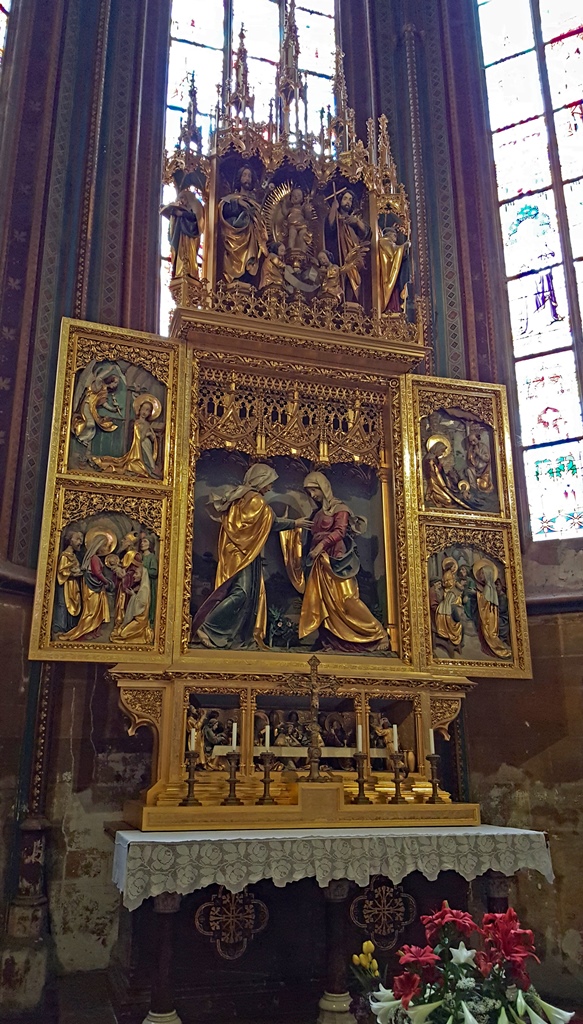

Main Altar

Pulpit (1618)

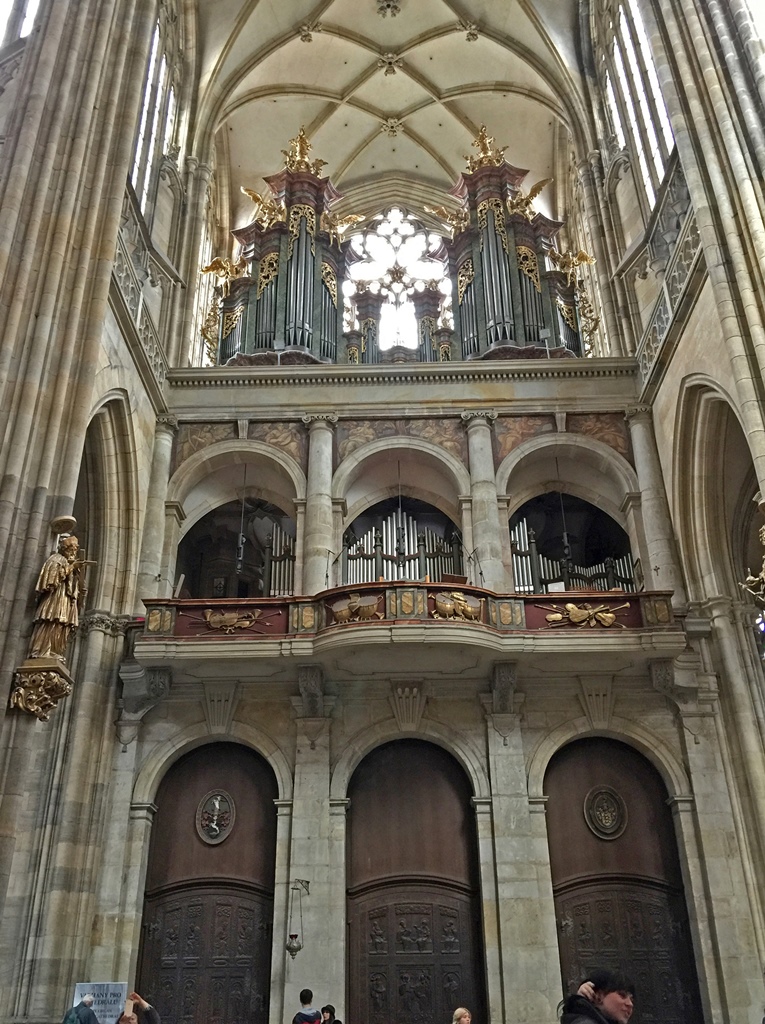

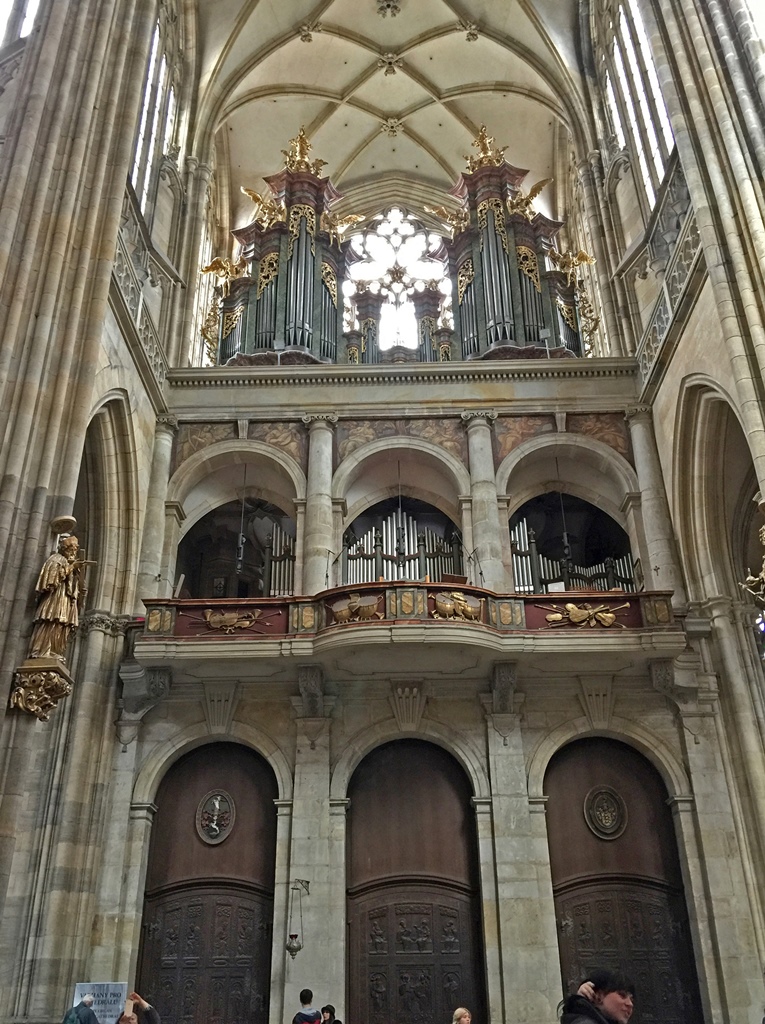

Organs

Organs

Royal Oratory

Royal Oratory, detail

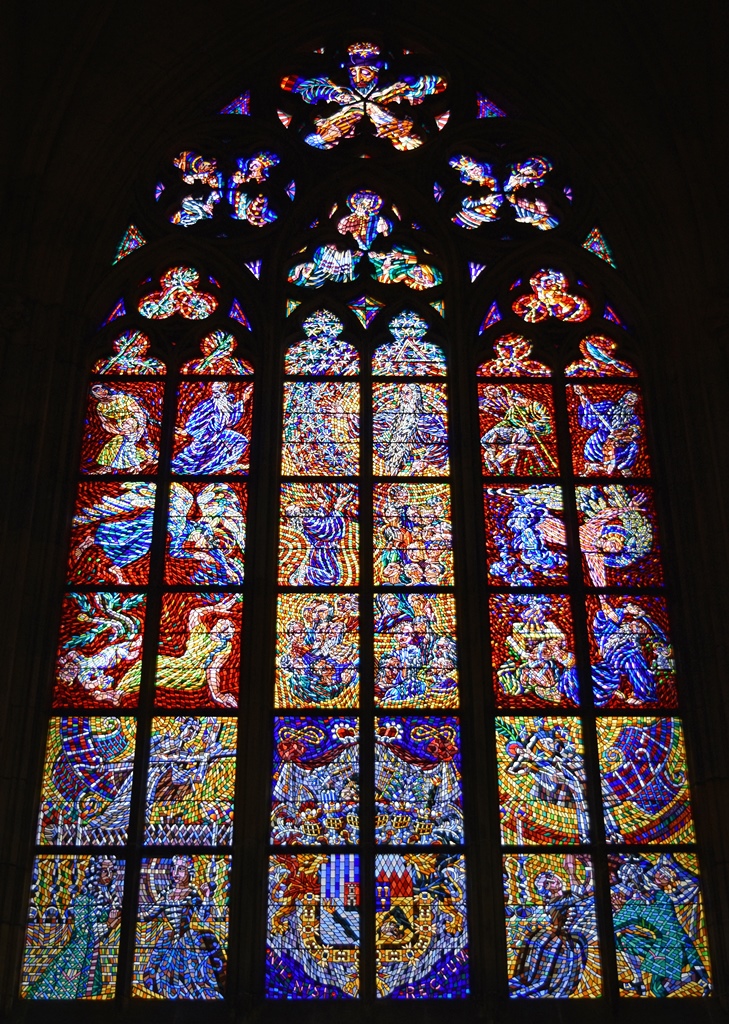

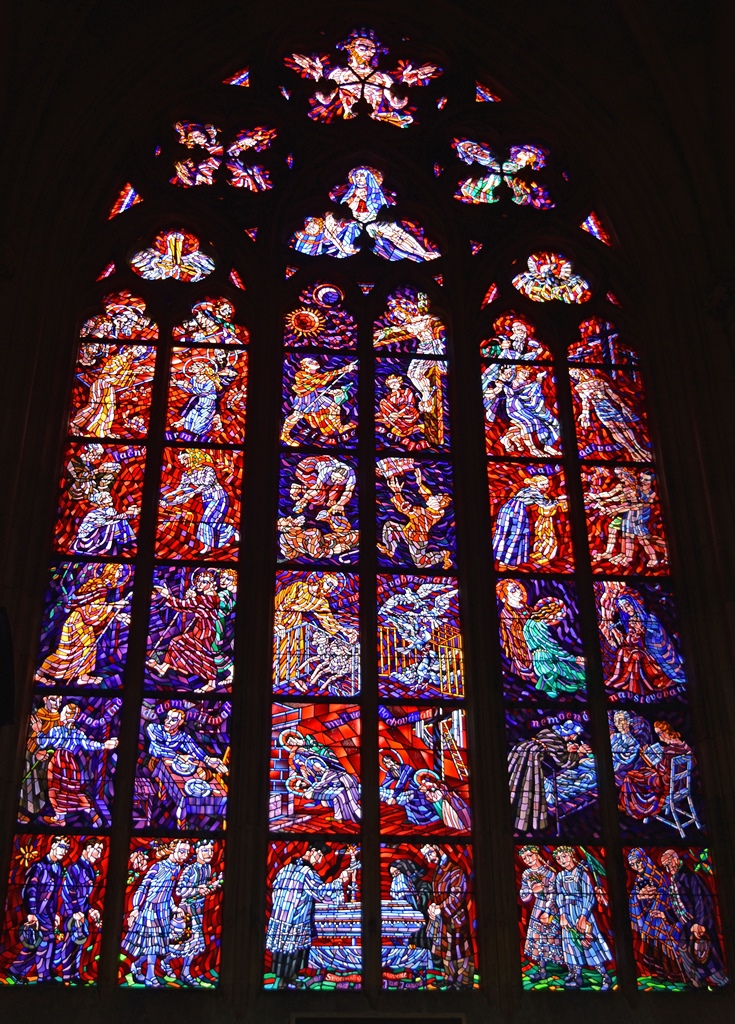

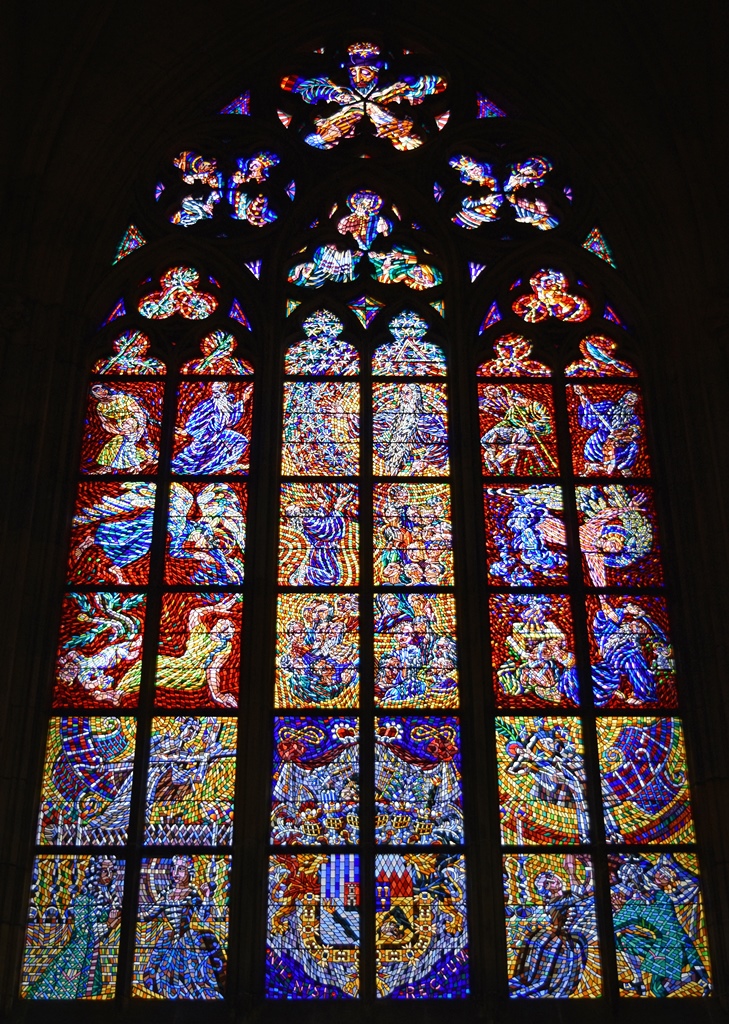

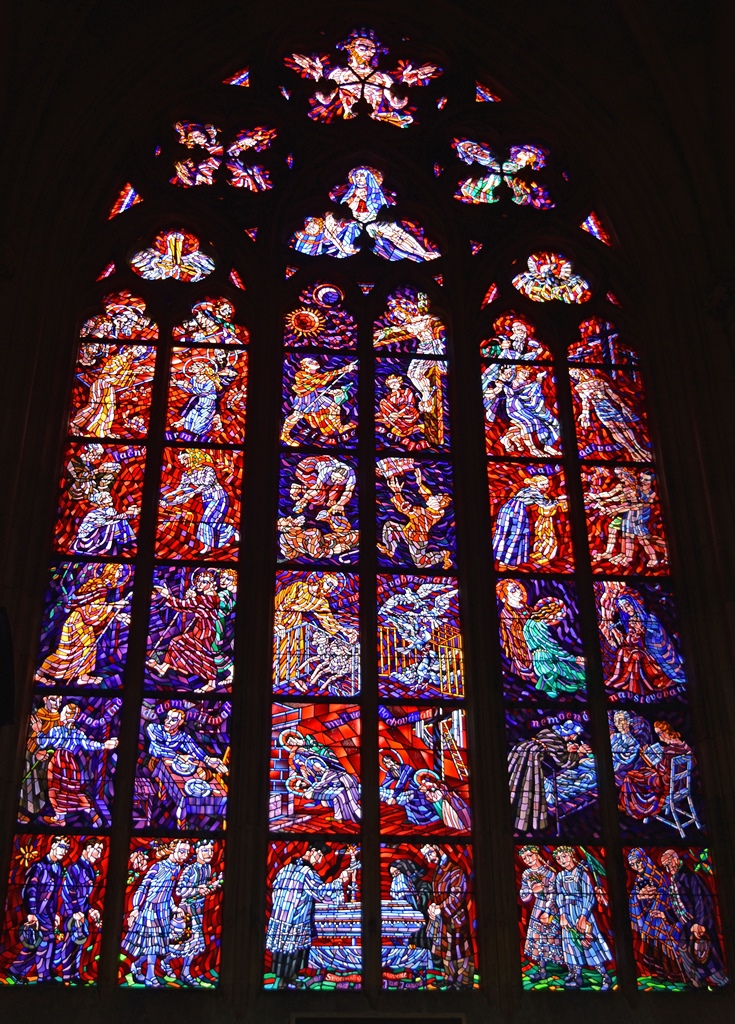

The cathedral is also full of interesting stained-glass windows. Most are 20th Century and most

are found above chapels.

The Eastern Window

Creation Rose Window

Schwarzenberg Chapel (Life of Isaac), Karel Svolinsky (1929)

Thunov Chapel

Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre, Karel Svolinsky

Chapel of St. Ludmila

Reliquary Chapel of St. John Nepomuk

Last Judgment Window, Max Švabinský

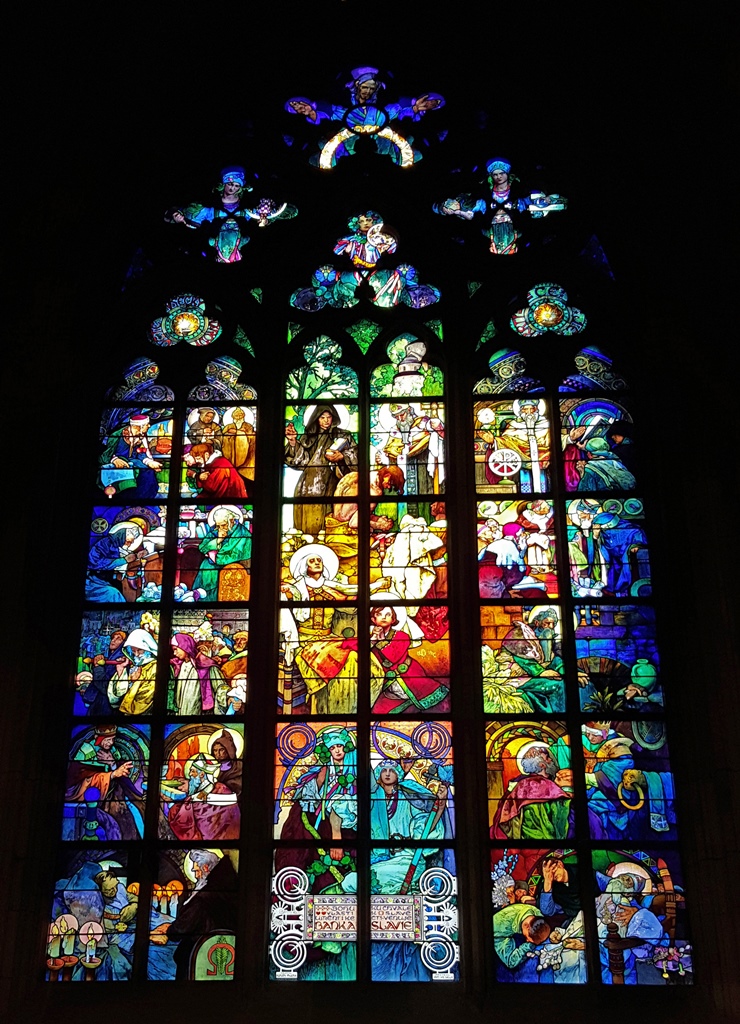

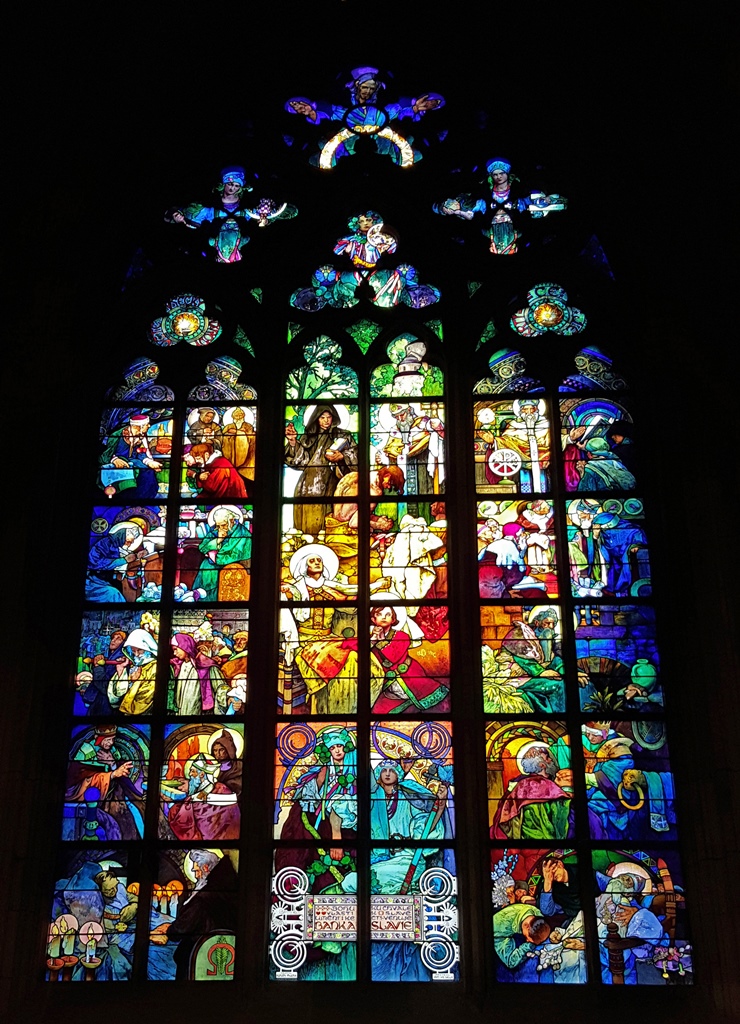

One window of particular note was designed for the New Archbishop Chapel by the popular Czech

artist Alphons Mucha around 1930. Mucha was best known for work he'd done in Paris, early in

his career, as a creator of art nouveau lithographs, mostly done as advertising. After making

his fortune in Paris, Mucha returned to his homeland and devoted his artistic attention toward

celebration of the Slavic peoples, eventually producing a monumental series of paintings known

as The Slav Epic. There will be a future page about this series, and we'll talk more

about Mucha at that time. For now, here's Mucha's window in the St. Vitus Cathedral. It isn't

technically stained glass, but instead a painting done on glass. The style might look familiar

to you.

Christ Blessing Slavic Nations, Alphons Mucha (1930)

Christ Blessing Slavic Nations, Alphons Mucha

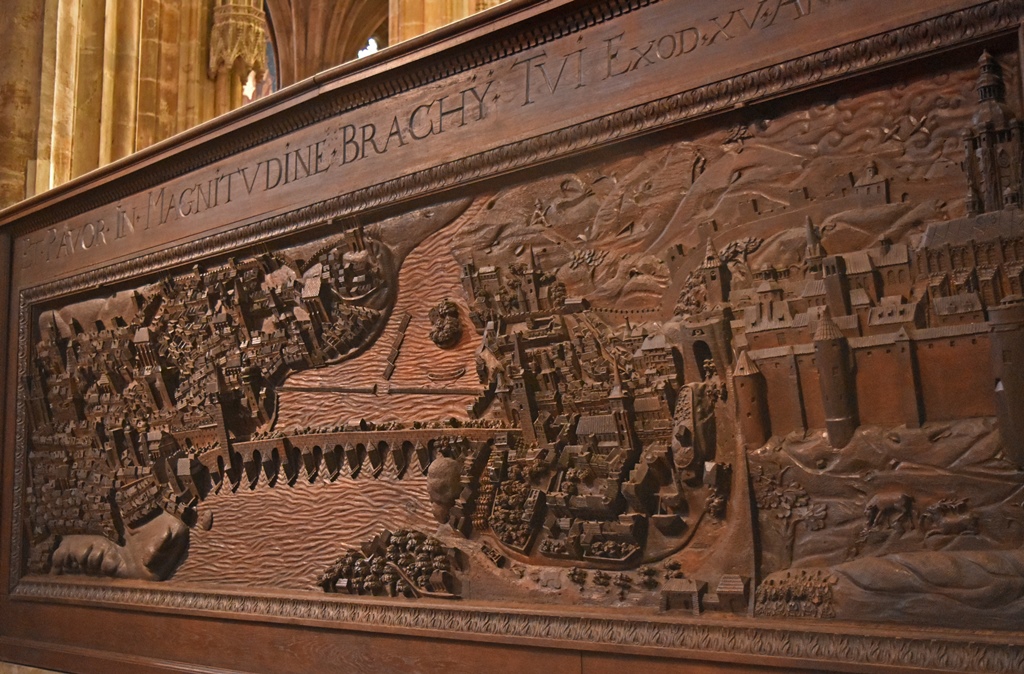

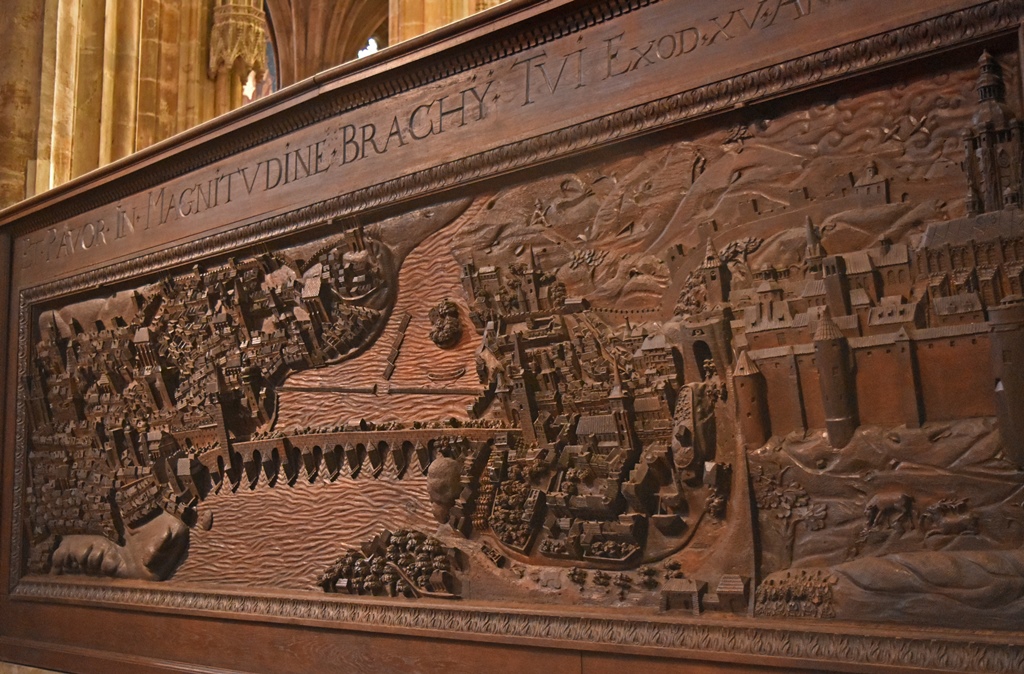

There are artworks scattered throughout the cathedral, some with no obvious connection to a

particular chapel. For instance:

Statues

Wood Carving of City, Gaspar Bechteler (17th C.)

And of course, there are many chapels as well. Here are a few of those:

Chapel of St. Sigismund

Chapel of St. Anne

Old Archbishop's Chapel

Chapel of Our Lady

Statue of Bedrich Schwarzenberg, Pernštejn Chapel

There is also a tomb for St. Vitus, or part of him – presumably the tomb holds the hand bones (some

sources say arm bones) that inspired Wenceslas I to devote a church to him.

Tomb of St. Vitus

Some tombs are showier than others. Here's a Baroque tomb, devoted to Leopold Anton Joseph

Schlik, who was Bohemian Chancellor and a Field Marshal during the War of the Spanish

Succession, early in the 18th Century.

Tomb of Leopold Anton Joseph Schlik (1663-1723)

The most spectacular tomb in the main cathedral area would have to be that of St. John Nepomuk,

who died in Prague in 1393. While it seems clear that he was murdered according to orders from

King Wenceslas IV, two reasons for the execution are typically given. One is that John served

as the confessor of the king's wife, and he refused to divulge information that he had received

in the confessional to her husband. The other reason has to do with papal politics. This was

the time of the "split" papacy, with one Pope in Rome and a second Pope in Avignon, France.

John apparently sided with his archbishop in supporting the Roman pope, while Wenceslas supported

the Avignon papacy. Whether either of these stories (or both) is the main reason behind John's

death seems to be unclear, but there's general agreement that John was tortured and then thrown

into the Vltava River from the Charles Bridge, where he drowned. John is now encased in a

fabulously Baroque 1736 tomb (by an artist named Fischer von Erlach) which incorporates a

prodigious amount of silver (two tons is the amount that is typically quoted).

Tomb of St. John Nepomuk (1736)

Tomb of St. John Nepomuk

Tomb of St. John Nepomuk, detail

Tomb of St. John Nepomuk, detail

Wenceslas IV, by the way, is also entombed in the St. Vitus Cathedral, in a relatively sedate

tomb in the royal crypt. We weren't able to view the crypt, but a fair representation of Bohemian

royalty can be found there, including Charles IV, who has a central place of honor.

Wenceslas I, however, is not found in the royal crypt. He has a special burial place, under a

special chapel that is not usually accessible to the public. This chapel has remained in the same

place since shortly after Wenceslas died, through the centuries as radical changes were made to

the church surrounding it. There are two doors into the St. Wenceslas Chapel, and sometimes one

or the other is open for viewing purposes only, but both doors were closed during our visit. But

during a previous visit in 2007, we had visited the cathedral when the western door to the chapel

happened to be open. As you can see, the wall decorations are copious, and apparently include

precious stones.

North Door to Chapel of St. Wenceslas

West Door to Chapel of St. Wenceslas

St. Wenceslas Chapel (2007)

St. Wenceslas Chapel (2007)

Somewhere in the chapel there is a locked doorway to a passage which leads to the place where

the Czech crown jewels are kept. The jewels are always kept in this place, except for one

day every eight years, when they are brought out to be viewed by the public.

But we weren't going to be hanging around that long, as the time had come for us to leave the

cathedral. We exited through a door in the west end of the church, across from the door we'd

entered through, and walked around to a courtyard on the south side of the church, from which

we could get a good look at it. The most prominent feature of the church from this side was

its 337-foot bell tower. The tower was half its present height when the long pause in

construction began. Sporadic attempts at resuming the construction were mostly unsuccessful,

but one of the few things that were eventually accomplished was completion of the bell tower,

which has an 18th Century spire that is stylistically Baroque.

Statue of St. George, South Courtyard

South Façade, St. Vitus Cathedral

Bell Tower

There are many interesting details on the church's exterior. There is a door on the south

side, usually locked, which enters between the bell tower and the St. Wenceslas Chapel. Before

the western end of the cathedral was finished, this was the main entrance. Above the doorway

is a mosaic of The Last Judgment, which dates back to about 1370.

South Façade, St. Vitus Cathedral

Last Judgment Mosaic

Gargoyle

Angels and Dead Christ

East End of Cathedral

We made our way around to the east end of the cathedral, on our way to visiting the rest

of the castle. On this side there is yet another courtyard, and in the courtyard there was

a vendor selling what looked like hot dogs (some kind of sausage on some kind of bread), and

it occurred to us that we were pretty hungry. We pulled out some korunas, bought hot dogs,

and dined on them al fresco.

Czech Hot Dog

Nella with Lunch

The hot dogs were quite good and the interlude quite welcome, but it soon occurred to us that

the rest of the world's largest castle was waiting for us. We got up, tossed our refuse into

the appropriate containers, and resumed our exploration of the castle.