Bob and British Museum

The British Museum is one of the world's

largest museums dedicated to human history and

culture. Its collection of roughly 13 million objects, mostly antiquities, was largely

acquired during the peak years of the British Empire, and is extraordinarily comprehensive.

When it was founded in 1753, it was envisioned as a repository for more universal subject

matter, including literature and natural history, and was opened in a former mansion, a

17th Century building called Montagu House. While Montagu House was large for a house, it

didn't take long for it to be overwhelmed by the growth of the museum's collections.

Plans for additional space were begun in 1802, but when George IV donated the

65,000-volume King's Library in 1822, it became clear that an expansion was urgently

needed. The architect Robert Smirke had been invited to come up with a redesign for the

museum in 1820, and his design was put into action starting in 1823. The plan was

ambitious and expensive, and was implemented in phases which did not complete until 1846.

The first phase was an eastern wing for accommodation of the Library, quickly followed by

a western wing, to be used for Egyptian antiquities.

Smirke's West Wing Under Construction, 1828

The original plan called for a large rectangular neo-classical building, with a grand

courtyard in the middle. The courtyard was soon judged to be wasted space, so most of

it was filled with a structure for storage of books and manuscripts, with a large,

circular reading room in the center.

As you might expect, this "museum of everything" was pretty unwieldy, and big parts of

it eventually ended up as museums of their own. Space for a proposed gallery of

paintings was in fact never used for this purpose, as the separate National Gallery was

founded in 1824, which made this space available for other things (natural history

collections, at first). Then in 1881, a building in South Kensington was completed to

house the Natural History collection (this was still considered part of the British

Museum until 1962, when it became its own thing). And finally, the British Library was

created by Parliament in 1973 to house all the publications, though an actual building

for this purpose (in the St. Pancras area) was not completed until 1997. This left the

British Museum as a much more specialized institution - but it's still really full of

stuff, as you'll see.

The British Museum was actually within an easy walk of our hotel. To get in, we had to

go through a checkpoint, but after that we were able to go right in. Admission was

free, and photography without flash was OK. The center of things is the Great Court,

which was opened up again after all the books were removed. The Reading Room remains

as a large cylindrical building which is now used for temporary exhibitions (our visit

was between exhibitions). The rest of the Great Court is again open space, but there's

now a glass roof covering the whole thing.

In the Great Court

The Reading Room

The courtyard is a space from which visitors can quickly get to any part of the museum.

We chose to first head for the western part of the museum, which turned out to have ancient

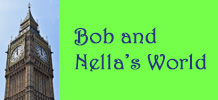

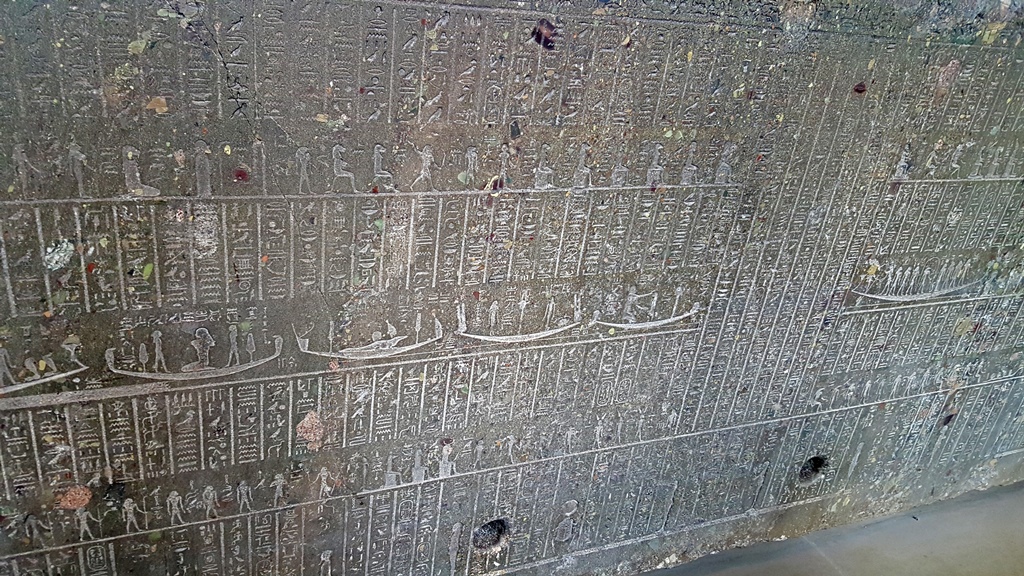

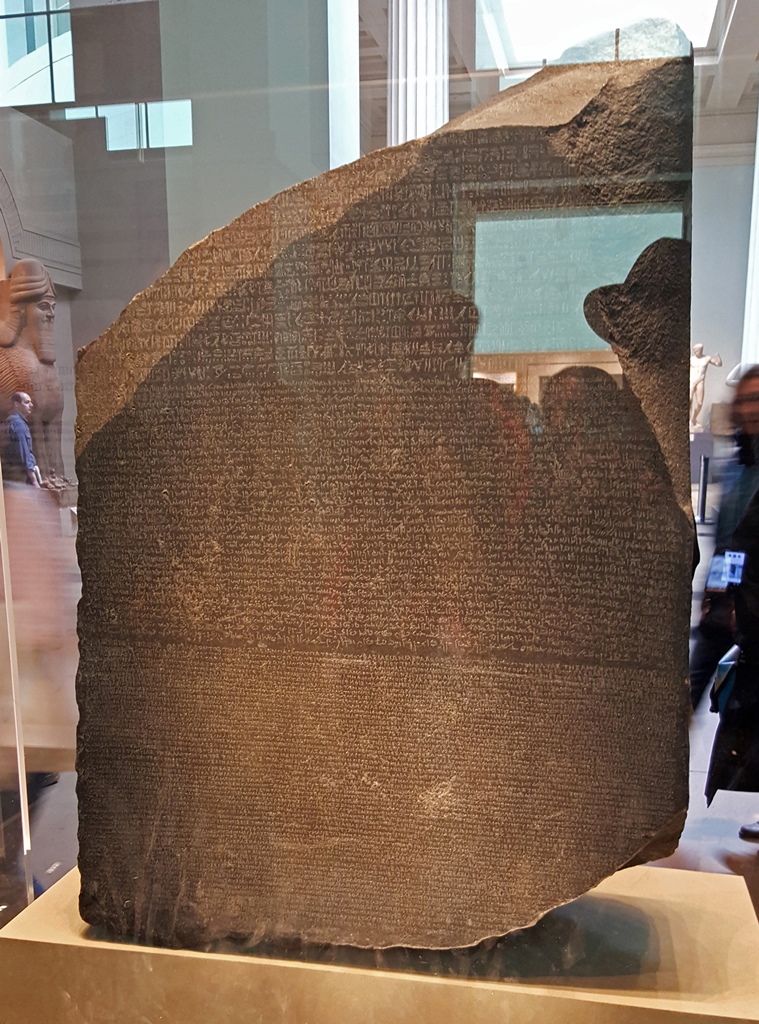

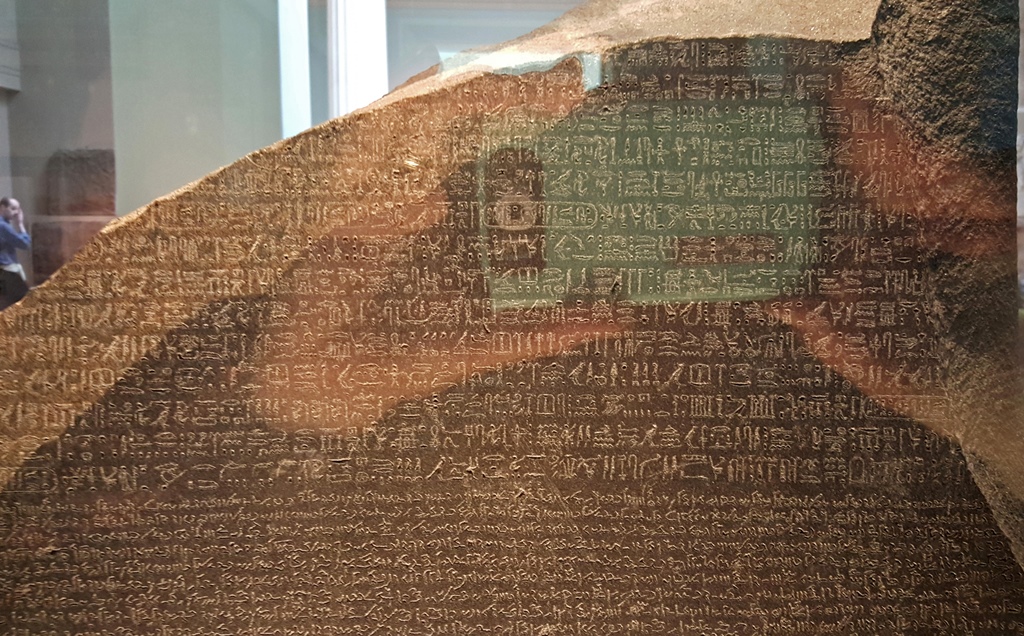

Egyptian displays. The first display we saw on the way in was the Rosetta Stone. Yes, the

actual Rosetta Stone. The stone dates back to 196 B.C., and was found in 1799 by a French

soldier during Napoleon's Egyptian campaign, near the town of Rosetta (or Rashid), in the

Nile delta. The British defeated the French in this campaign, in 1801, and took the stone

from them. The stone displays the text of a Ptolemaic decree in three different written

languages: hieroglyphics, Demotic script (a character-based version of Egyptian) and Greek.

As of 1799, nobody had been able to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, but Greek was

well-known. The stone gave researchers a previously-unknown way to understand the

inscriptions with which ancient Egyptian tombs, temples and artifacts were covered, and

opened up a whole new understanding of ancient Egypt.

The Rosetta Stone (196 B.C.)

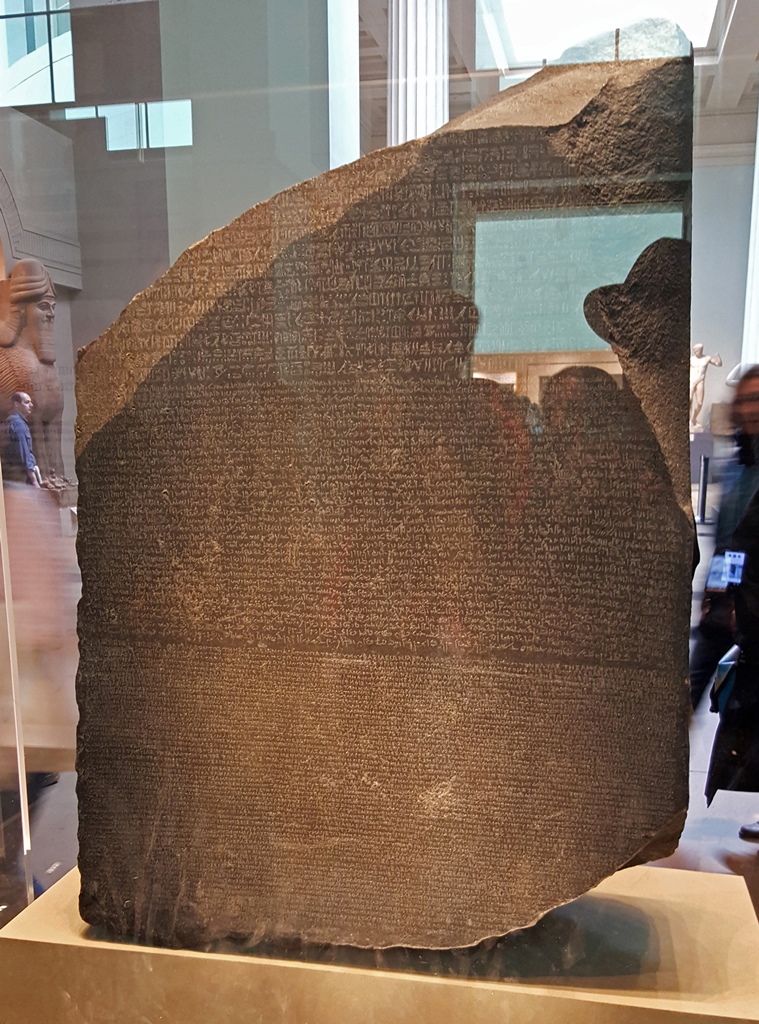

Rosetta Stone Detail (Hieroglyphic and Demotic Sections)

Just past the Rosetta Stone was a large room with displays of Egyptian sculpture.

Egyptian Gallery

The British Museum has a large collection of Egyptian artifacts, in fact the largest

collection of Egyptian antiquities in the world, except for the Egyptian Museum in Cairo

(currently in the process of transitioning to the new Grand Egyptian Museum, across the

river in Giza). In order to impose some order on the following pictures, I'll present

them roughly chronologically, divided by recognized periods of Egyptian history. Since

Egyptian history goes back more than 5,000 years, it has a lot of recognized periods. A

few whose names you might recognize are the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms (the terms are

relative - the "New Kingdom" ended more than 3,000 years ago). But there is also a

period before the Old Kingdom, "intermediate periods" between the kingdoms and several

periods more recent than the New Kingdom. Fortunately our pictures are from only a few

of these periods, so this shouldn't be too complicated.

First, here's our only picture of a Middle Kingdom artifact. The Middle Kingdom lasted

from 2055 through 1650 B.C. It's not clear exactly where in Egypt this boat model came

from (it was purchased from a private collection), but it's typical of objects which

were encased in tombs along with the deceased.

Model of a Boat (ca. 1985-1795 B.C.)

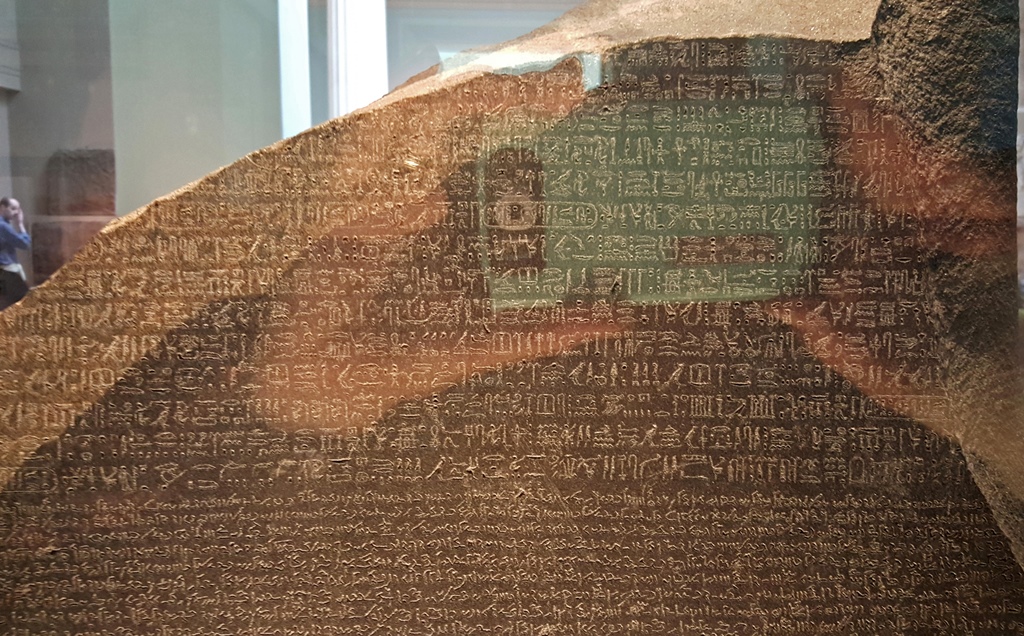

This next group of photos is of objects from the New Kingdom, which lasted from 1550

through 1069 B.C. (there was a 100-year Intermediate Period between the Middle and New

Kingdoms). This was the period of the most famous pharaohs (Thutmose III, Amenhotep III,

Ramesses II, Tutankhamun) and many famous tombs and monuments. The beard of the Sphinx

was likely an add-on by Thutmose IV (the Sphinx is much older, dating back to the Old

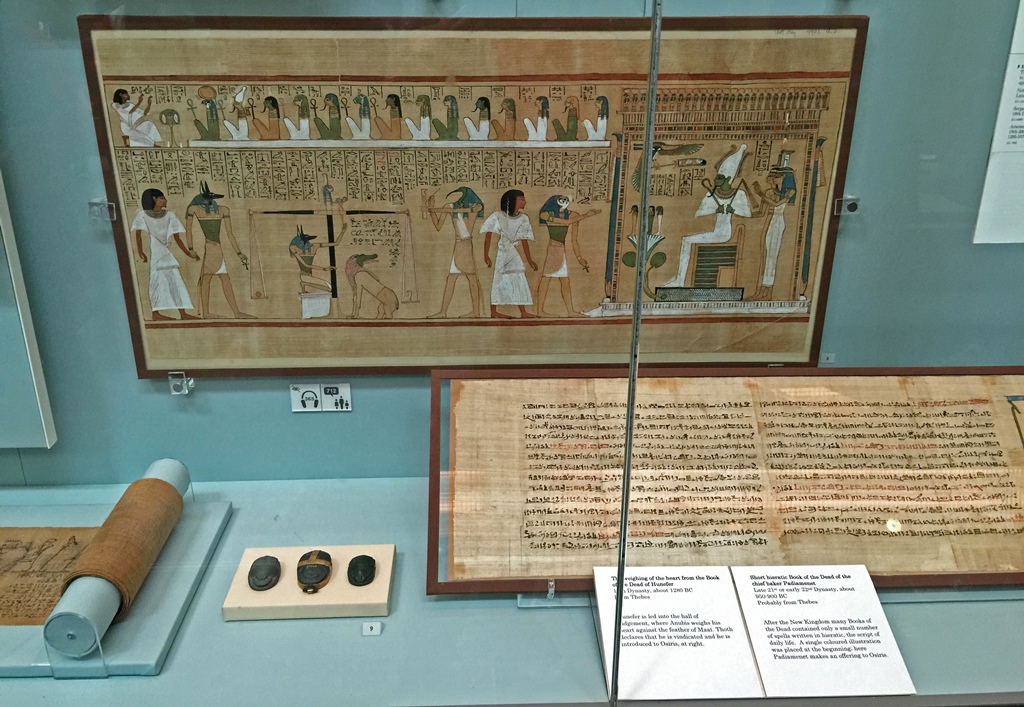

Kingdom) that fell off at some point. The New Kingdom is also when the Book of the Dead

came into use. There were many versions of the Book of the Dead, which were buried with

the deceased and contained information and magic spells to assist them in the underworld.

Book of the Dead with Weighing of the Heart

Fragment of the Beard of the Sphinx, Giza (ca. 1420 B.C.)

Great Sphinx of Giza and Pyramid of Cheops (2019 photo)

King Amenhotep III, Thebes (ca. 1390-1352 B.C.)

Amenhotep III, Karnak (ca. 1390-52 B.C.)

Nella with Statues of Sekhmet, Karnak (ca. 1390-52 B.C.)

Amenhotep III as a Lion, Sudan (ca. 1390-1352 B.C.)

Nebamun Hunting in the Marshes, Thebes (ca. 1350 B.C.)

Rameses II Statue, Thebes (ca. 1279-1213 B.C.)

Roy (High Priest of Amun-Ra), Thebes (ca. 1220-1200 B.C.)

After the New Kingdom, there was a 400-year intermediate period that lasted until 664 B.C.

You'd think a period lasting 400 years would rate a better name than "intermediate", but I'm

not an Egyptologist. Anyway, here are a couple of items from the Third Intermediate Period:

Coffin of the Priest of Khons, Nespernebu, Thebes (ca. 800 B.C.)

Ram Sphinx of King Taharqo, Sudan (690-664 B.C.)

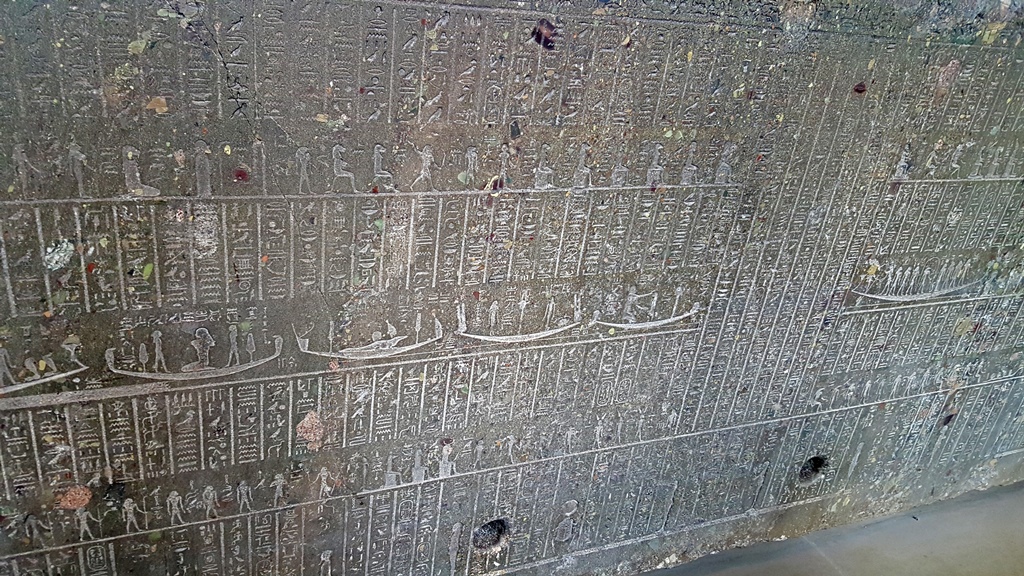

This gave way to the Late Period, which lasted until 332 B.C.:

The Gayer-Anderson Cat, Saqqara (ca. 600 B.C.)

Detail, Sarcophagus of Nectanebo II, Alexandria (360-343 B.C.)

The last period represented in our pictures began with the reign of Alexander the Great,

who conquered Egypt in 332 B.C. After Alexander died in Babylon in 323 B.C., his empire

started to crumble, and there were disputes over succession in various parts of it,

including Egypt. Relatives and friends of Alexander were involved in the Egypt dispute,

and the eventual victor was Alexander's friend Ptolemy, who took the title of Pharaoh

Ptolemy I. This began the Ptolemaic Dynasty, which would continue until 30 B.C., at which

time it would end with the death of the last Ptolemaic ruler, Cleopatra VII. This whole

period is called the Ptolemaic Kingdom, and here's a picture of a giant bug from this period:

Colossal Scarab, Heliopolis (3rd-2nd C. B.C.)

One last picture of Egyptian artifacts shows shabtis from various periods. Shabtis

were small figures that were commonly placed in tombs, beginning way back during the Old

Kingdom, that were expected to become animated and perform manual labor when the deceased

needed them.

Assorted Shabtis

Moving on from Egypt, we found rooms of artifacts from ancient Britain and Ireland. One

such artifact was a Bronze Age gold cape, which was thoroughly restored by the museum

after it was found in Wales in 1833:

Gold Cape, Wales (ca. 1900-1600 B.C.)

Here are more artifacts, some of which go back to Roman days:

Bronze Head of Claudius, Suffolk (1st C. A.D.)

The Mildenhall Great Dish, Suffolk (4th C. A.D.)

The Londesborough Brooch, Ireland (8th-9th C.)

The Lewis Chessmen, Scotland (12th C.)

There were also some decorative objects from the 18th Century, which seemed as though

they would be more at home in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. But

they were in the British Museum instead, and here are a few of them:

Porcelain Vase and Cover, William Littler's Factory (ca. 1755)

Pair of Musicians in Arbours, Chelsea Factory (ca. 1758-69)

Musical Table Clock with Automata, Stephen Rimbault (ca. 1765)

There were also some religious objects from continental Europe, and here are a few of those:

The Adoration of the Three Wise Men, Tilman Riemenschneider (ca. 1505-10)

Adam and Eve Chastised by God, Urbino (1608)

Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, Doccia Factory, Florence (ca. 1750)

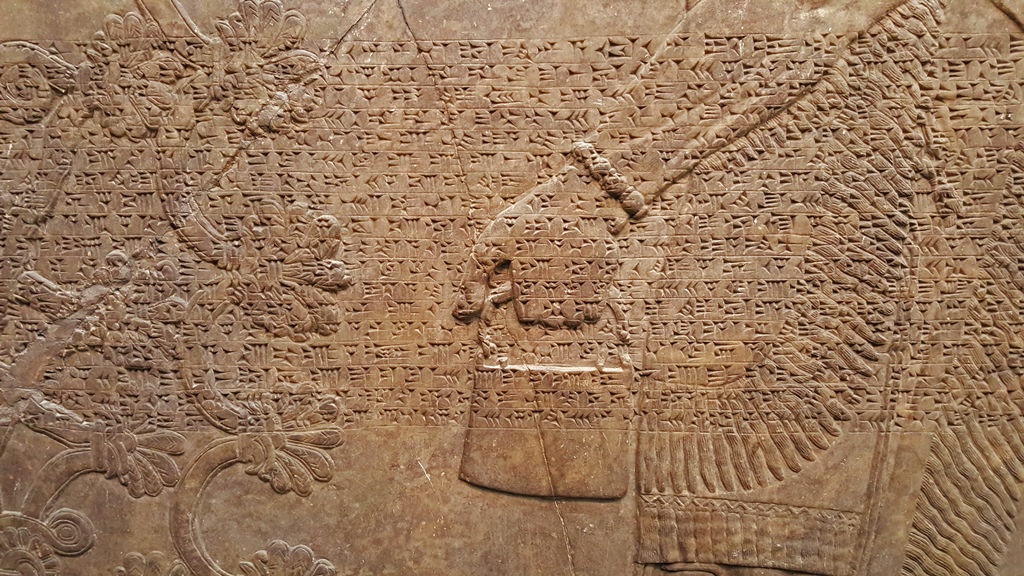

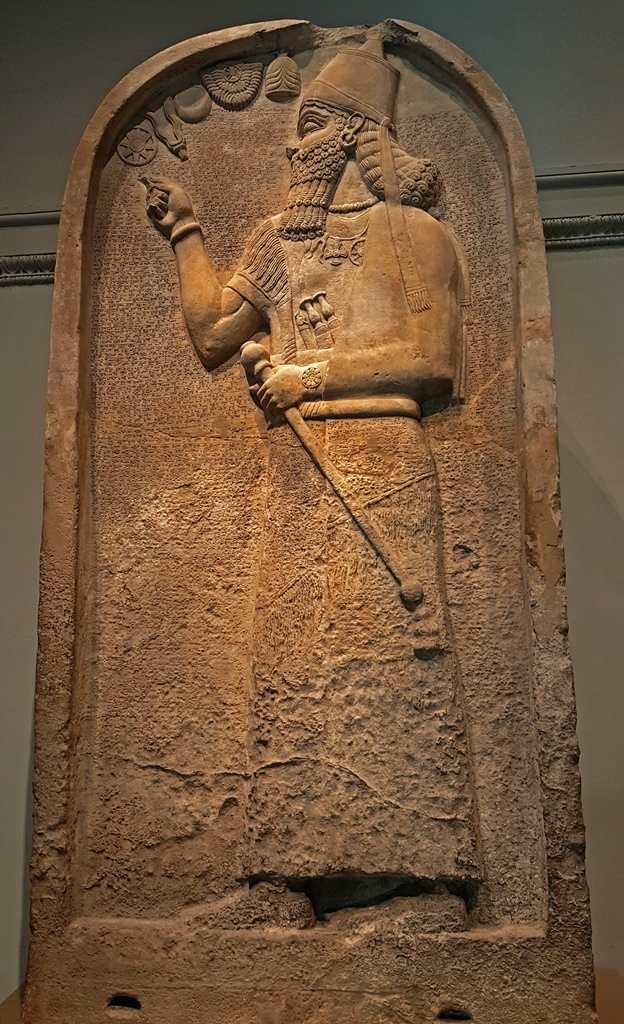

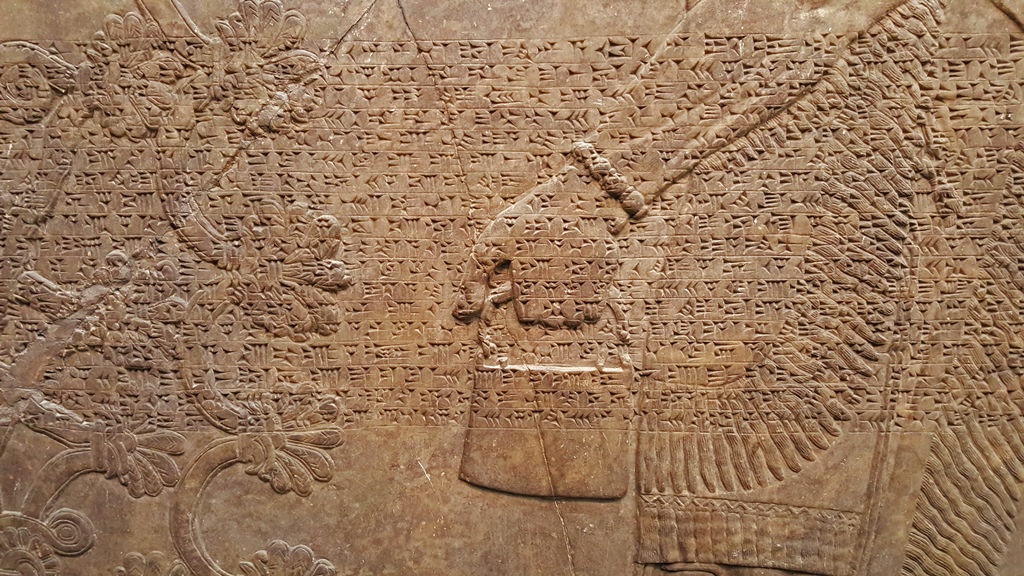

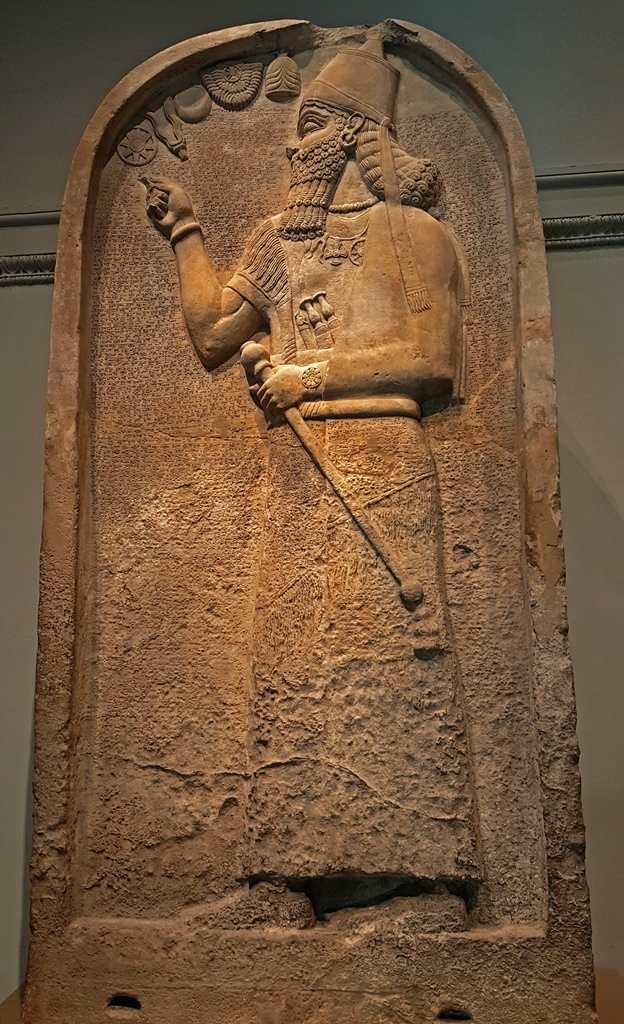

Moving back to the first millennium B.C., here are some objects from Assyria, which was

located in present-day Iraq:

Colossal Guardian Lion, Temple of Ishtar (ca. 865-860 B.C.)

Human-Headed Winged Lions, Nimrud, Assyria (ca. 865-860 B.C.)

Eagle-Headed Protective Spirit, Temple of Ninurta (ca. 865-860 B.C.)

Protective Spirit's Magic Purse with Cuneiform

Gypsum Stela of the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II, Nimrud (9th C. B.C.)

Lion Hunt, Nimrud (ca. 865-860 B.C.)

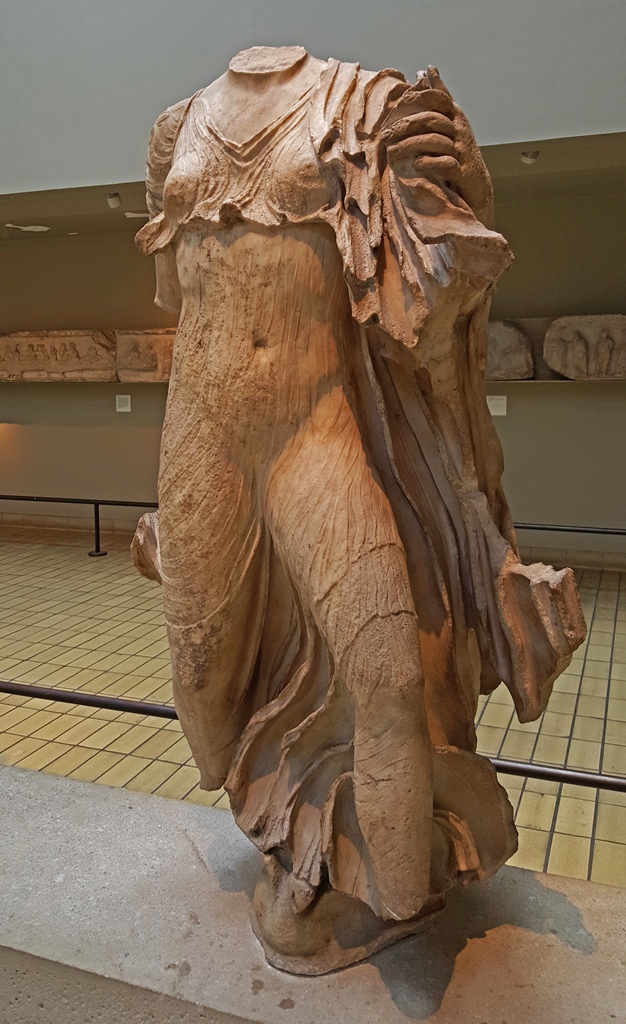

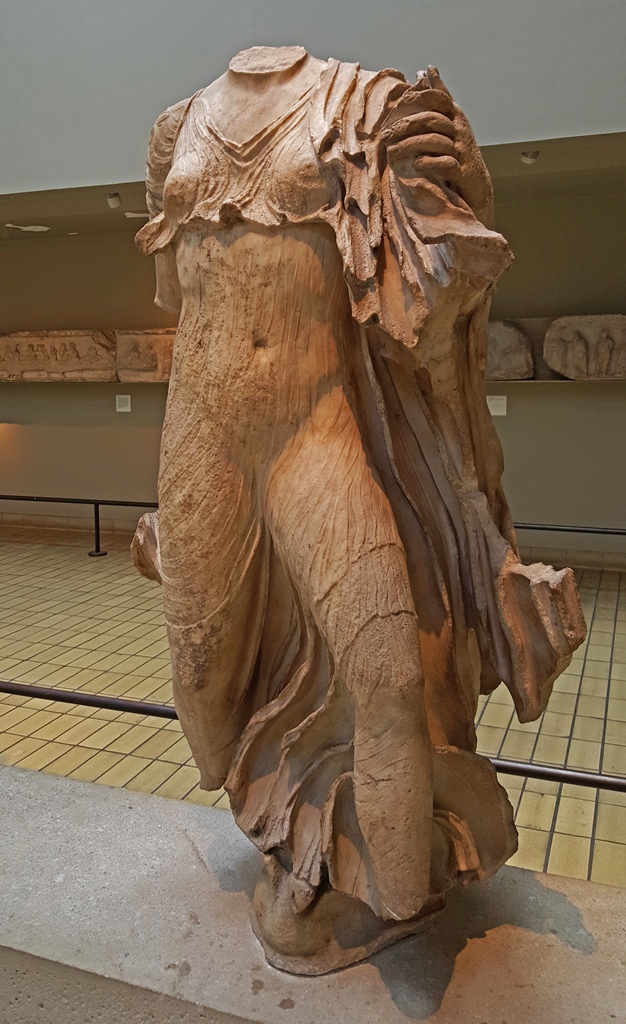

From here we moved through some rooms with objects found in modern-day Turkey. First,

we found a room holding a reconstructed Nereid Monument from the city of Xanthos.

Nereids are sea nymph daughters of the god Nereus, and the construction of the

Nereid statues reflects a strong Greek influence (and may have been done by Greek

sculptors). The monument was built by the Lykian people, members of a civilization

that was virtually unknown until these artifacts were discovered between 1838 and 1844.

Nereid Monument, Xanthos, Turkey (ca. 390-380 B.C.)

Nereid from the Nereid Monument

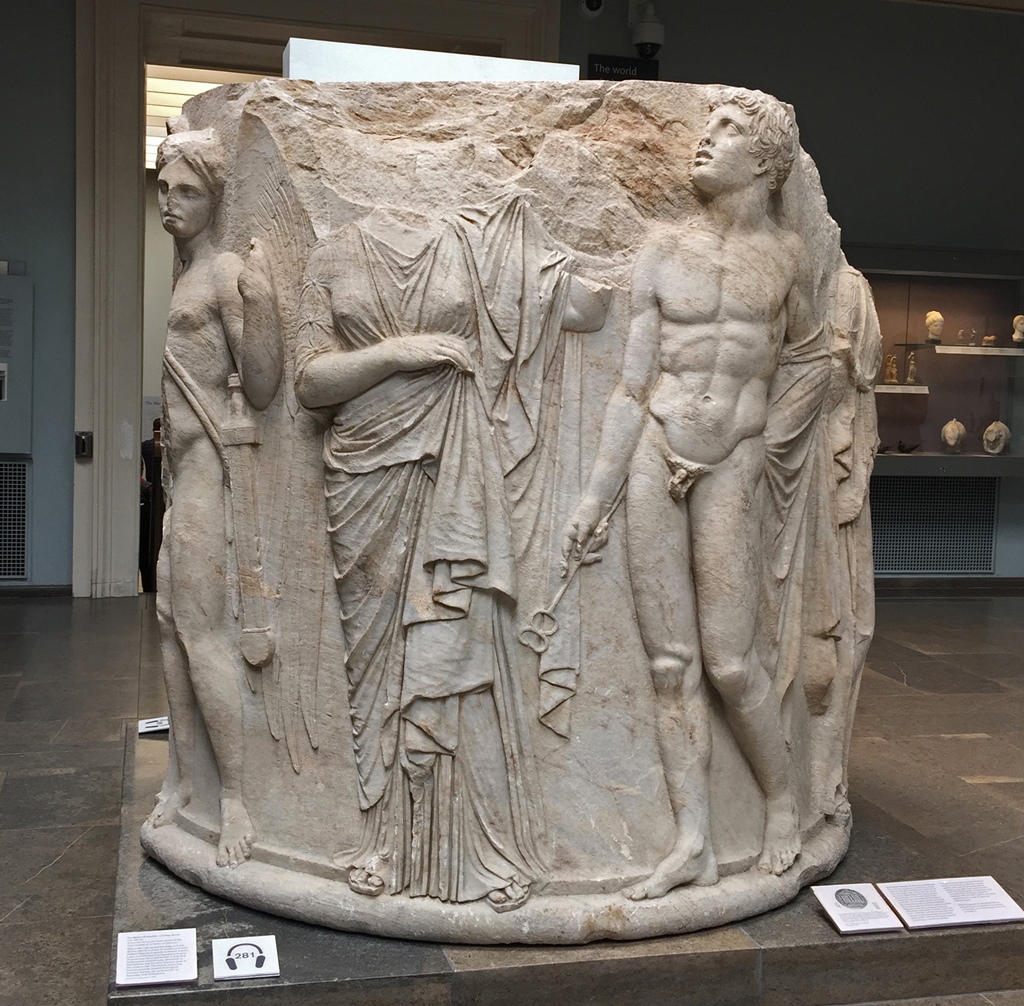

Next we found a room with some remains from one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient

World, the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos. The Mausoleum was built around 350 B.C. as a

tomb for Maussollos, governor of Karia in southwest Asia Minor, which was then part

of the Persian Empire. When intact, the Mausoleum was 140 feet high and had a

pyramid-shaped roof with a four-horse chariot group (or quadriga) at the top.

There was a frieze running around the base depicting a battle between Greeks and

Amazons.

Maussollos and His Wife Artemisia

Horse from Quadriga

Frieze Scene of Battle Between Greeks and Amazons

The museum also has artifacts from other parts of Asia Minor, from around the same period:

Gold Oak Wreath, Dardanelles (350-300 B.C.)

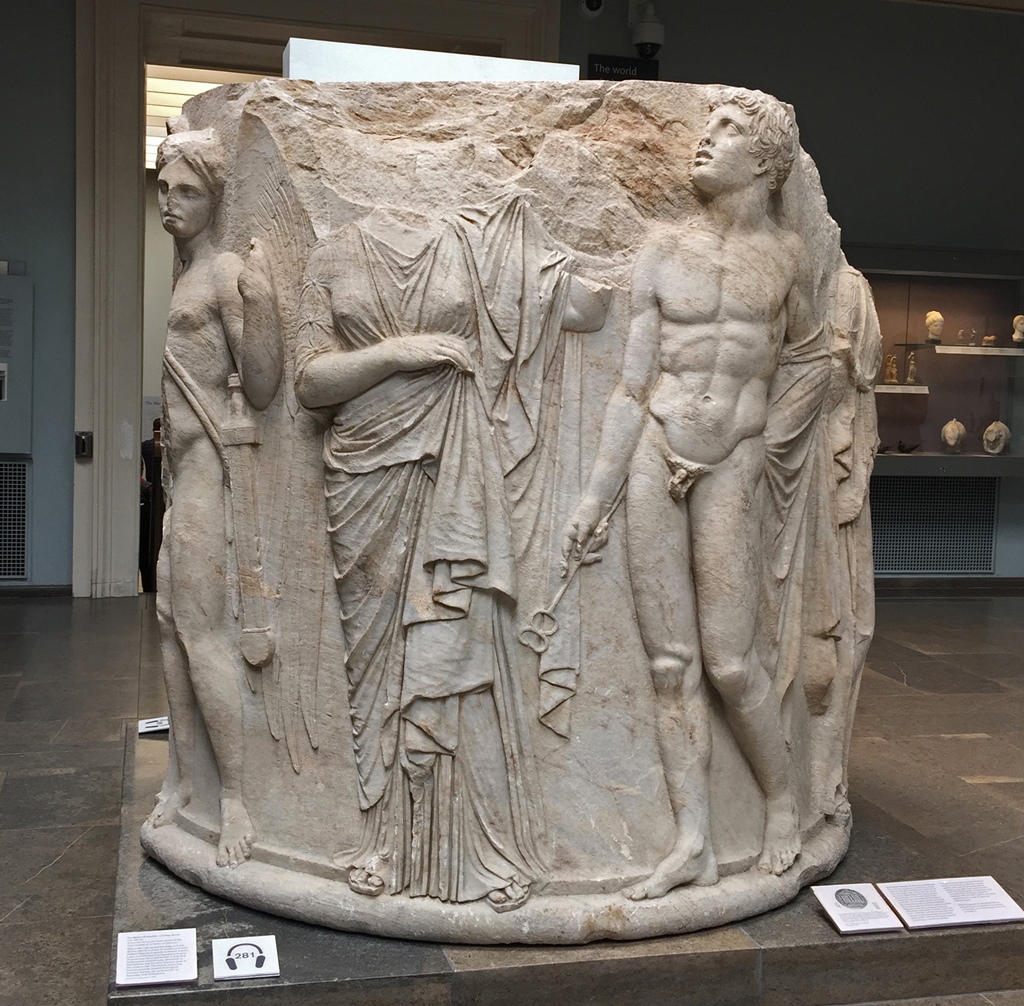

Sculptured Marble Column Drum, Ephesos (325-300 B.C.)

We didn't see too much in the way of Roman artifacts, but we did see this interesting 4th

Century drinking vessel, known as the Lycurgus Cup. This is a cup known as a "cage cup",

which means that it started as a plain glass cup, but its surface was ground back

selectively to leave a surface-level design. In this case, the design depicts the mythical

King Lycurgus being ensnared by a vine into which a follower of Dionysus had been

transformed (the unfortunate king did not survive the encounter). A couple of things set

this cup apart from other cage cups. First, most cage cups were decorated with geometric

designs, and this is the best-preserved cage cup known to exist which depicts actual

figures. Second, the cup is made of something called "dichroic glass", which appears green

when lit from the front, but red when light is shown through it.

The Lycurgus Cup, Rome or Alexandria (4th C. A.D.)

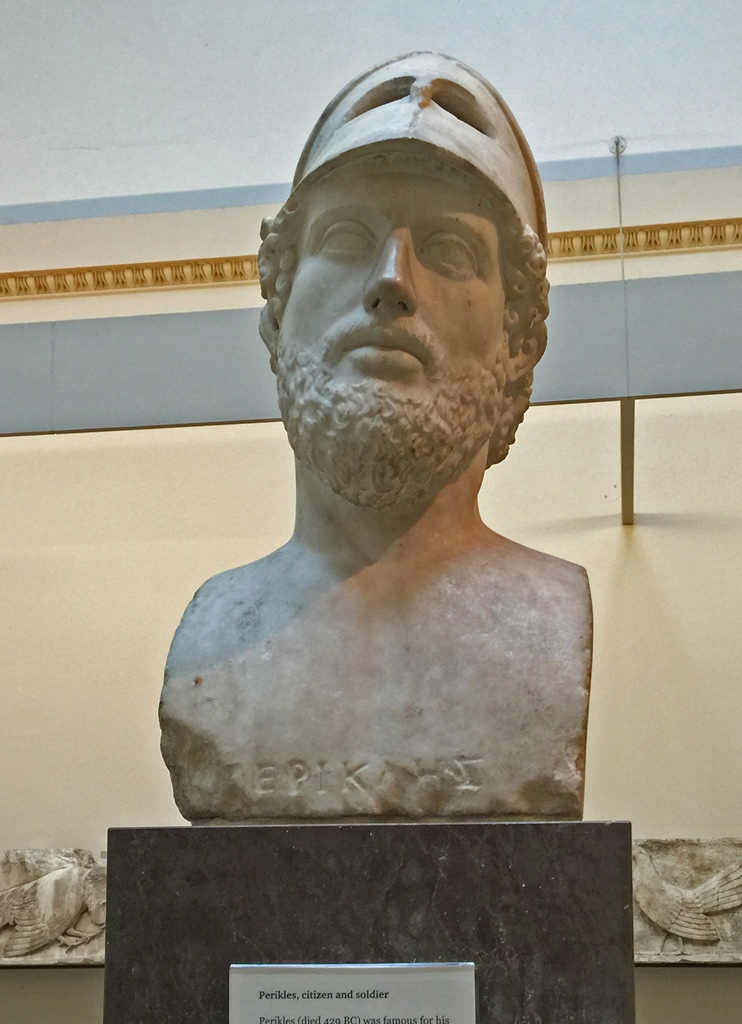

This brought us to what is possibly the most famous of the museum's possessions and

almost certainly its most controversial, this being the Parthenon Marbles, otherwise

known as the Elgin Marbles. The Parthenon, of course, is the large temple to Athena

which is found on top of a hill called the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. The Parthenon

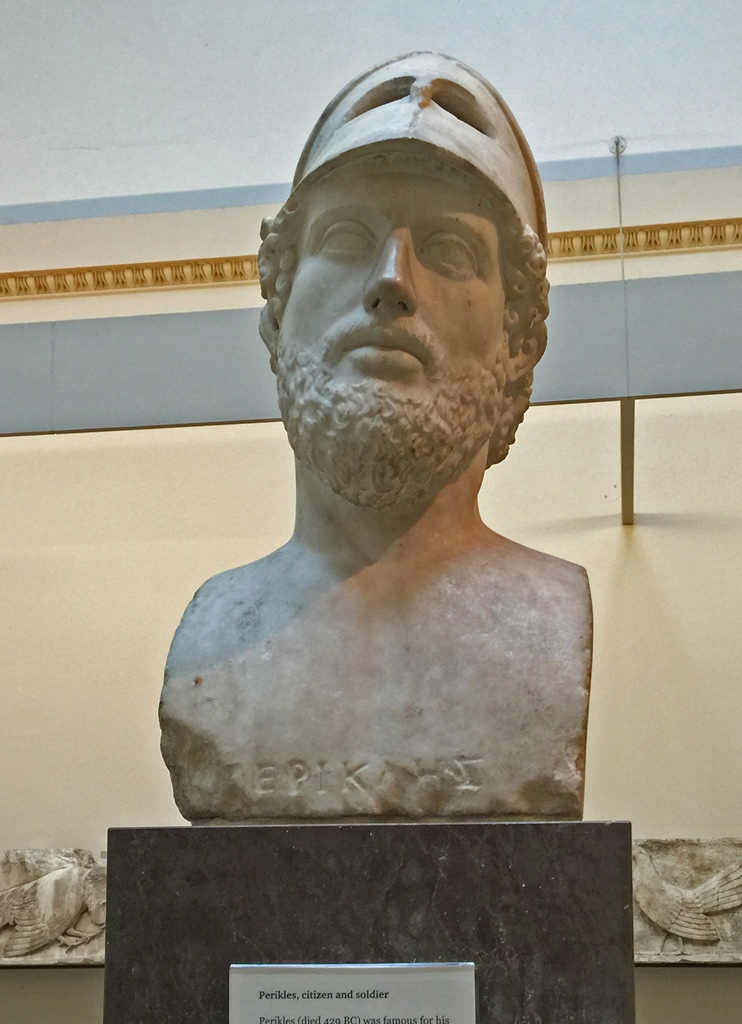

was built from 447-432 B.C. at the direction of Pericles, the great general and ruler

of Athens. There was plenty of space for a temple, as the Persians under Xerxes I had

sacked the city and destroyed everything on top of the Acropolis in 480 B.C.

The Parthenon (2019)

Bust of Pericles, Roman Copy (2nd C. A.D.)

The Parthenon is 228 feet long, 101 feet wide and 45 feet tall, thus presenting a lot of

surface area for decoration. And the best sculptors in Athens decorated with great energy.

The decorations were of three different types. First, sculptures were created for the

pediments, the triangular areas at the top of each end of the temple. Second, sculpted

panels called metopes were lined up just under the edge of the roof, with 92 metopes

stretching all the way around the temple. And third, there was a frieze which extended

around the cella, which was a smaller structure (98 feet by 68 feet) located within

the temple.

Reconstruction of West Pediment Sculptures

Model of Parthenon, Showing Location of Metopes

Over the centuries, the Parthenon became a Christian church, and later, after the conquest of

Greece by the Ottoman Turks, the Parthenon became a mosque. In 1687, the Turks were using the

Acropolis as a defensive fortification during a war against the Venetian Republic, and they

used the Parthenon as a powder magazine. A Venetian artillery round struck the magazine and

ignited a blast that killed 300 people, while causing catastrophic damage to the Parthenon.

The central part of the building was essentially destroyed, with the loss of the roof and the

collapse of three of the four walls of the cella. Venetian soldiers looted some of the

sculptures, and over the following century, many additional pieces of the structure were looted

by locals for building material.

In 1801, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin and British Ambassador to the Sultan of Turkey

undertook the task of making drawings and plaster casts of the surviving sculptural elements

found on the Acropolis. Later that year, he started removing sculptural elements from the

Parthenon wreckage and from other structures on the hill and sending them back to England. By

the time he finished, in 1812, he had taken more than half of the surviving structural

elements from the Parthenon, including 21 figures from the pediments, 15 metope panels and

nearly 250 feet of the cella frieze. In 1816, Lord Elgin ended up selling the marbles to the

British government, for about half of what he'd spent to acquire them.

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin (1788)

In 1832, Greece gained independence from the Ottoman Empire and started tracking down

antiquities that had been looted and dispersed to various other countries around the world.

High on their list were the Elgin Marbles, by this time on display at the British Museum. But

the British Museum refused to return the marbles, maintaining that they'd been legitimately

acquired, and that they were now an integral part of the museum's collection. They said that

the Sultan at the time, Selim III, had been grateful for Britain's opposition to the

expansionist activities of Napoleon, and that the marbles weren't of any particular value to

him, so he'd signed a decree giving Lord Elgin permission to remove whatever material he

wished. But no such decree has ever been found, which is suspicious, considering the Turks

were normally meticulous record-keepers.

And this is pretty much how things stand to the present day. The Greeks would very much like

to have the marbles back, and even have spaces reserved for them in their recently-built,

state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum. The British Museum insists that they (or their distant

predecessors, to be more precise) behaved honorably throughout the acquisition of the marbles

and the dispute over them, and that if they started returning items in their collection to

their countries of origin, they would soon have no collection left. So the Parthenon Marbles

continue to reside at the British Museum, in a room called the Duveen Gallery, which was

specifically built for them in the 1930's. Here's the gallery, and figures from the

Parthenon pediments:

Duveen Gallery with the Parthenon Marbles

Figures from the West Pediment

Figure of Iris, West Pediment

Figures from East Pediment

Reclining Dionysos, East Pediment

Hestia, Aphrodite and Dione, East Pediment

All of the recovered metopes appear to have come from the south side of the temple, and

they all depict a battle between Lapiths (a legendary tribe from Thessaly) and centaurs.

Lapith Fighting with Centaur

Lapith Fighting with Centaur

Centaur Carrying Off Girl

The surviving frieze sections depict a thanksgiving procession following a successful battle.

Horsemen, South Frieze

Portion of East Frieze with Hermes and Dionysos

This seemed like a good time to move on to another part of the world, like all the way

to the South Pacific and Easter Island.

Basalt Figure from Easter Island

Well, maybe not that far. Maybe just to Asia, and Burma (present-day Myanmar):

Lidded Offering Vessel, Burma (19th C.)

Here are some ceramic figures from different eras of Chinese history:

Tomb-Figures, North China (8th C.)

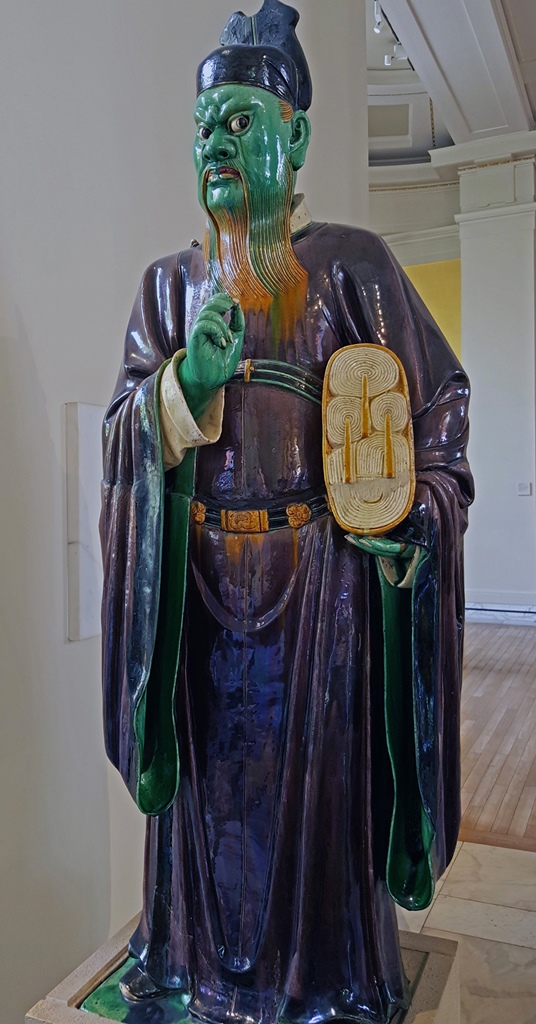

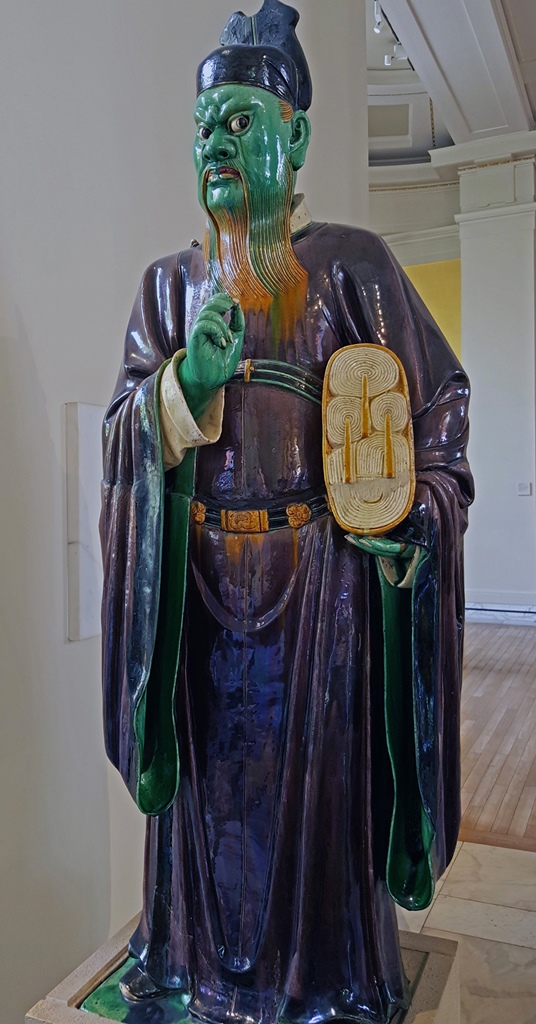

Figure from a Judgement Group, Ming Dynasty (16th C.)

Standing Military Figure, Ming Dynasty (1626)

Here's a sculpture from early 19th Century Tibet:

Yamantaka Vajrabhairava (Buddhist Deity), Tibet (19th C.)

Moving over to Japan, here's a wooden sculpture of Monju Bosatsu. But it's possible that

you don't know who Monju Bosatsu is. I have to admit I had to look this up. Sources

tell me that Monju Bosatsu is a Bodhisattva. This didn't really clear things up for me,

but it turns out that a Bodhisattva is an enlightened Buddhist being that goes around

between rebirth cycles helping people. Monju Bosatsu embodies the Buddha's wisdom, and

has a flaming sword that cuts through ignorance. He also rides on a lion that roars with

the sound of Buddhist law. Not to upset any Buddhists out there, but Monju Bosatsu sounds

a little on the cartoony side. Not that that's necessarily uncool...

Monju Bosatsu, Koyo (1685-89)

Moving back to India, here are a couple of items from the museum's Indian collection. FYI, Shiva

and Parvati are Hindu deities that are married to each other.

Column Base, Western India (11th C.)

Shiva and Parvati, India (12th-13th C.)

From the Asian displays, we walked across the central courtyard of the museum to the

Enlightenment Gallery. This is in the east wing of the building and is its oldest

room, with a room number of 1. It was originally designed to hold the Library of

George III, which stayed here (with a couple of temporary moves during the world wars

for its protection) until it was moved to the new British Library in 1997. The room

is now devoted to the Age of Enlightenment (also known as the Age of Reason), which

lasted roughly from 1680 until 1820, when people were energetically trying to figure

out the world around them, in the process collecting numerous natural and archaeological

specimens and writing scholarly books about them or speculating about them. A number

of these objects are on display, along with very brief or frequently nonexistent

descriptions.

Nella in Enlightenment Gallery

Seashell Collection

Adjacent to the Enlightenment Gallery, also in the east wing, is a room in which the

Waddesdon Bequest is displayed. This collection was bequeathed to the museum by

Baron Ferdinand Rothschild in 1898, and consists of objects he'd kept in his Smoking

Room at Waddesdon Manor, in Buckinghamshire. There is an impressive amount of metal

and ceramic work in the collection.

Objects from the Waddesdon Bequest

Cup with Shell Cameos, Nuremberg (1525-50)

The Ulm Book Covers (ca. 1506)

Vase, Saxony (1670)

The Woman of the Apocalypse, Limoges (ca. 1570)

Assorted Pendants

Nautilus Cups, Dutch (1594-1650)

We finally finished with the British Museum, and though there was still much of interest

in London that we hadn't seen, we'd about finished with the city also, as we needed to

prepare for travel the next day. We would be flying from a capital city in western

Europe, where we were (mostly) familiar with the language, to another capital city, but

in eastern Europe, where the language would be quite difficult. We would be embarking

on an adventure to the city of Prague.