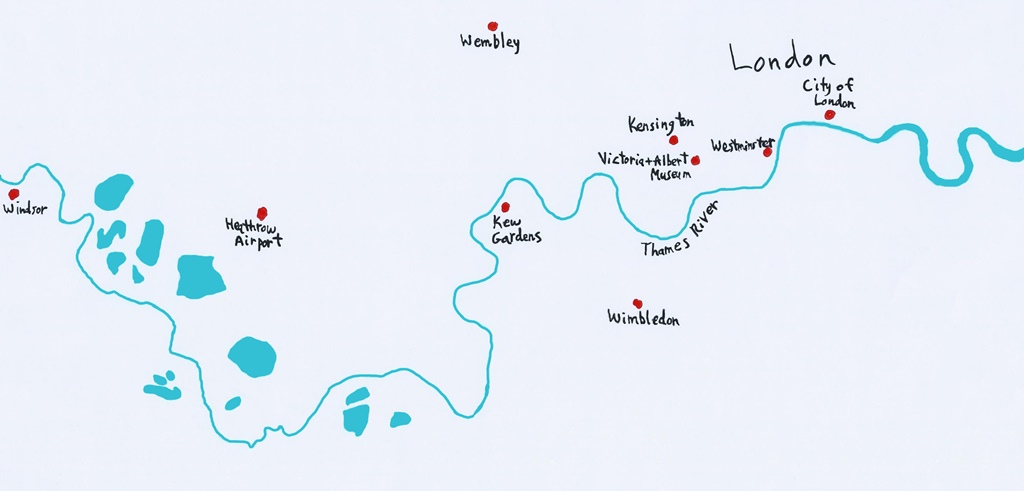

London Area

The Victoria and Albert Museum (popularly referred

to as the V&A), located in South Kensington, is the largest museum of its kind in the

world. From its name, it's not obvious what this kind is – one might guess that it's

all about its namesakes, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, but this isn't really the

case. Before receiving its present name, it was called the South Kensington Museum,

which is even less descriptive. Its original name, the Museum of Manufactures, gives

you some idea of what the museum used to be about, but this has changed drastically.

To resolve the question, we'll start by looking a little more closely at the Queen and

the Prince.

Queen Victoria, 1837

Prince Albert, 1840

Queen Victoria was crowned Queen of the United Kingdom in 1837, at the age of 18, and

would occupy the throne for the rest of her life, which would last an additional 63

years. In 1840, she married Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (in Germany), who was

her first cousin (Victoria's mother and Albert's father were brother and sister).

Victoria and Albert were much devoted to each other and would produce nine children,

all of whom would survive to adulthood.

The Royal Family, 1846 (5 children and counting)

Albert, unfortunately, would only survive until the age of 42, at which time he

would succumb to a stomach ailment (diagnosed as typhoid fever at the time, but

it may have been something more long-term, like cancer or Crohn's disease).

Victoria was overwhelmed by grief, and would wear black for the rest of her life.

Queen Victoria, 1875

In the happier days of their youth, Albert was at first not as happy as he might have

been. Britain by this time was a constitutional monarchy, meaning Victoria's actual

governing power was quite limited. And Albert, being just the consort to the Queen,

had no governing power at all, beyond whatever influence he had on his wife. This

was frustrating for a man who'd been raised to become a Duke of Saxony, and he ended

up occupying himself by devoting himself to civic and charitable causes, such as

education reform and the abolition of slavery. In the 1840's, Albert became

president of the Society of Arts, which produced annual exhibitions of its work.

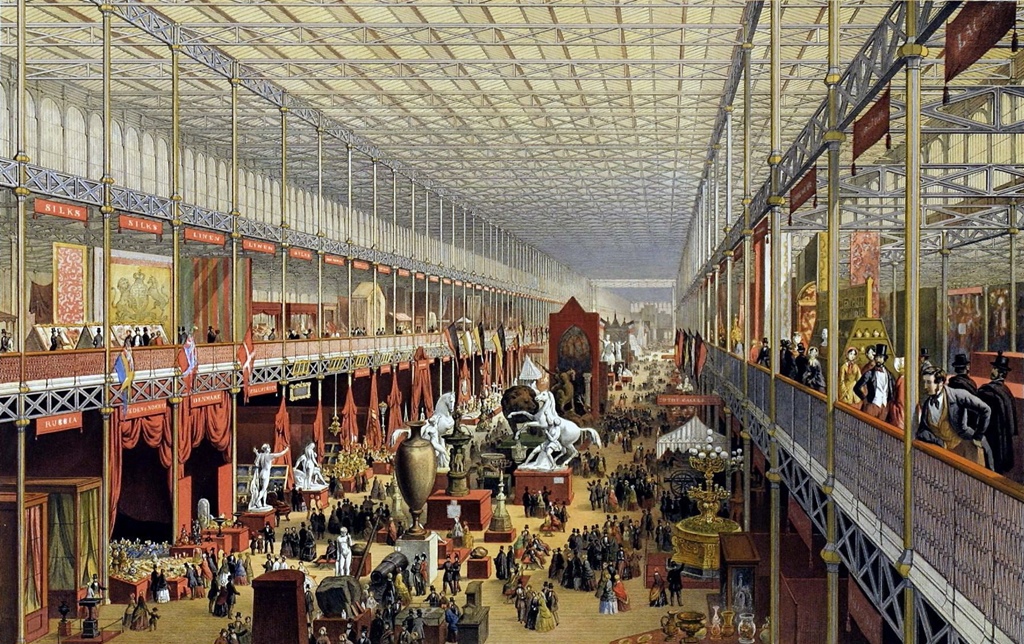

This led to his presiding over a much bigger international exhibition in 1851, the

Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, a sort of World's Fair held

in Hyde Park in London. Exhibitors from throughout the world were invited, with

particular emphasis on the many colonies of the British Empire. A huge temporary

structure called the Crystal Palace was constructed for the purpose.

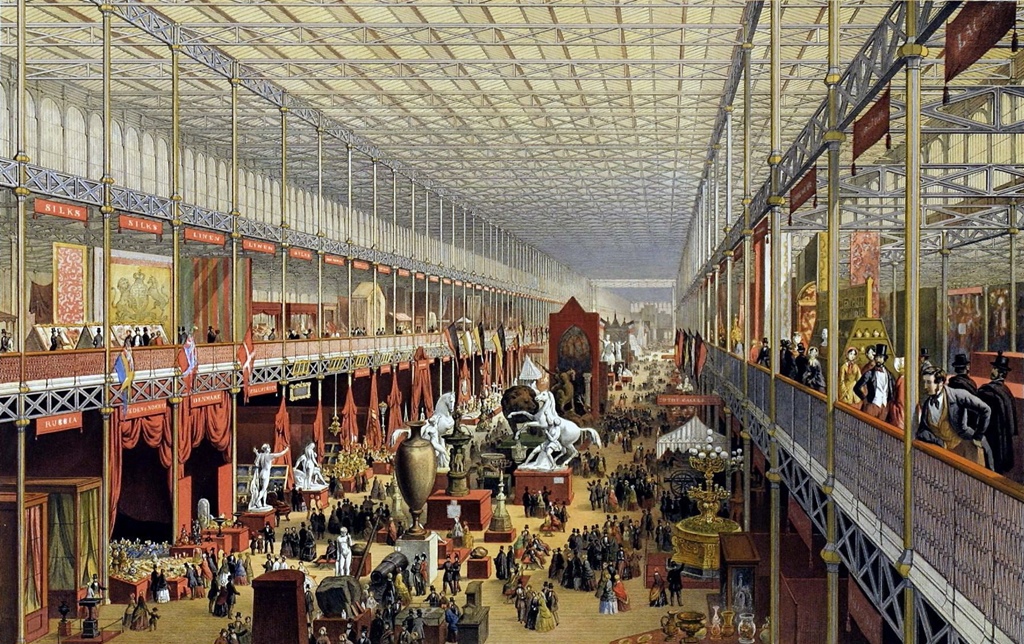

The Crystal Palace

Inside the Crystal Palace

Despite the predictions of many, the Great Exhibition was a resounding success,

attracting more than 6 million visitors and making a profit that would be big enough

to fund future projects. The idea for the first project was an obvious one: a

permanent museum that would showcase the sorts of exhibits that made the Great

Exhibition so popular. This museum opened in 1852 as the Museum of Manufactures, in

Marlborough House, in the vicinity of Buckingham Palace, but later the same year it had to

move to larger quarters at Somerset House, on the bank of the Thames. Many of the

first exhibits had been purchased directly from exhibitors at the Great Exhibition.

Despite the museum's name, the exhibits also included artistic and scientific ones

that had little to do with industry. In 1857 the museum moved again, to a site in

South Kensington that was purchased using the aforementioned profits, and it became

the South Kensington Museum.

Over the ensuing decades, new objects were added to the museum's collections until

it became necessary to exhibit some of them in improvised off-site locations, and it

was decided to do this with the scientific exhibits, while keeping the artistic ones

in the main building. This led to the eventual creation of a separate Science

Museum, leaving the Victoria and Albert Museum (officially renamed at Queen

Victoria's last public appearance in 1899) as essentially what it is now - a museum

of applied and decorative arts and design. And sculpture. But not much ancient

art, as this is mostly at the British Museum (see next page). And not much fine

art, as this is mostly at the National Gallery. And not much modern art, as there

are other museums for this stuff too. Anyway, you can make up your own description

for the V&A after looking at the pictures below.

Like the British Museum and the National Gallery, admission to the V&A is free.

The museum has a permanent collection of more than 2 million objects and covers 12.5

acres, and we didn't allocate nearly enough time to explore it in much detail (like

earlier in the day, when we'd done the same thing at Kew Gardens). But we went on

in and did our best with it.

Cromwell Road Entrance to Museum

Entry Dome

Glass Sculpture, Dale Chihuly (1999-2001)

In the first room, we found that "decorative arts" included the decoration of people.

There wasn't too much of this – this is probably the most elaborate suit of clothing we saw:

Court Suit, France (ca. 1795-98)

"Applied arts" refers to art objects that have a purpose, beyond art for art's sake.

Like furniture, for example:

Dresser, Portrait and Candelabras (England, France, Germany)

Pier Table, Genoa (1740-60)

Cabinet on Stand, Paris (ca. 1660-71)

Cabinet, Antwerp (1650-60)

Table Cabinet, Naples (ca. 1600)

Cabinet on Stand, Naples (1680-1710)

Tile Stove, Hans Kraut (1577-78)

Cabinet, Alexandre Eugène Prignot (1855)

Washstand, William Burges (1880)

There was also an impressive selection of ceramics on display, some porcelain and some

terracotta.

Nature, Sèvres Factory, Paris (1794)

Stand for Sweetmeats, Meissen Factory, Dresden (ca. 1735)

Möllendorf service, Meissen Factory, Dresden (ca. 1761)

Flower Pyramid, Delft (ca. 1695)

Vase (Earthenware), Victor Etienne Simyan (1867)

Virgin and Child with St. Diego of Alcala (Terracotta), Madrid (1690-95)

The Adoration of the Kings (Terracotta), Andrea della Robbia (ca. 1500-10)

Cupid and Psyche (Terracotta), Claude Michel (ca. 1797-1800)

While wandering around the exhibits, we kept running into urns for some reason. A common

decorative accent during a certain era, perhaps. Here are some of the more interesting

ones:

Beaded Urn, Germany (1755-72)

Decorated Urn

Steel Urn, Russia (ca. 1800)

There were also some musical instruments on display. Again, works of art:

Glass Virginal, Innsbruck or Nuremberg (1604-20)

Octave Spinet, Italy (ca. 1600)

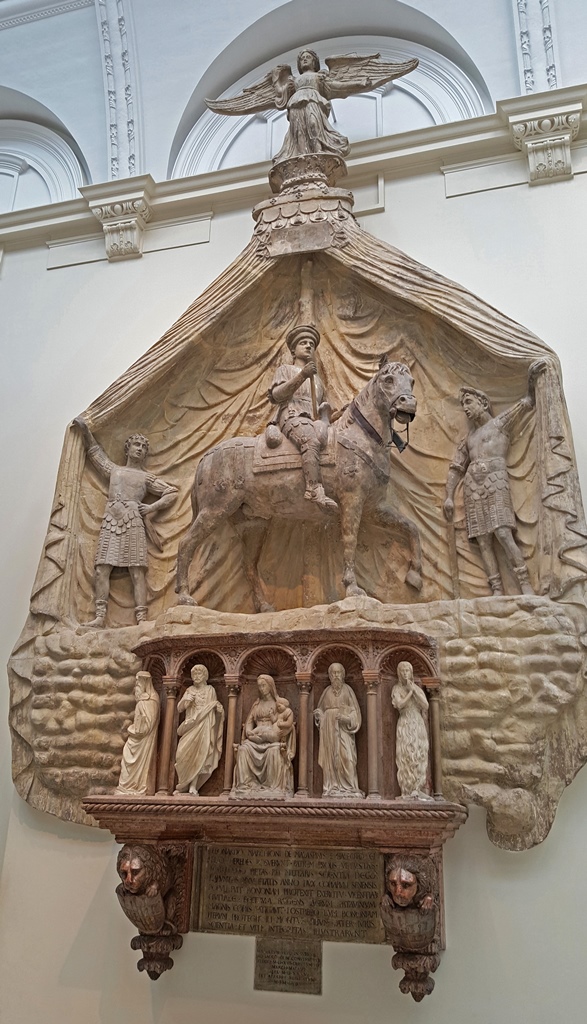

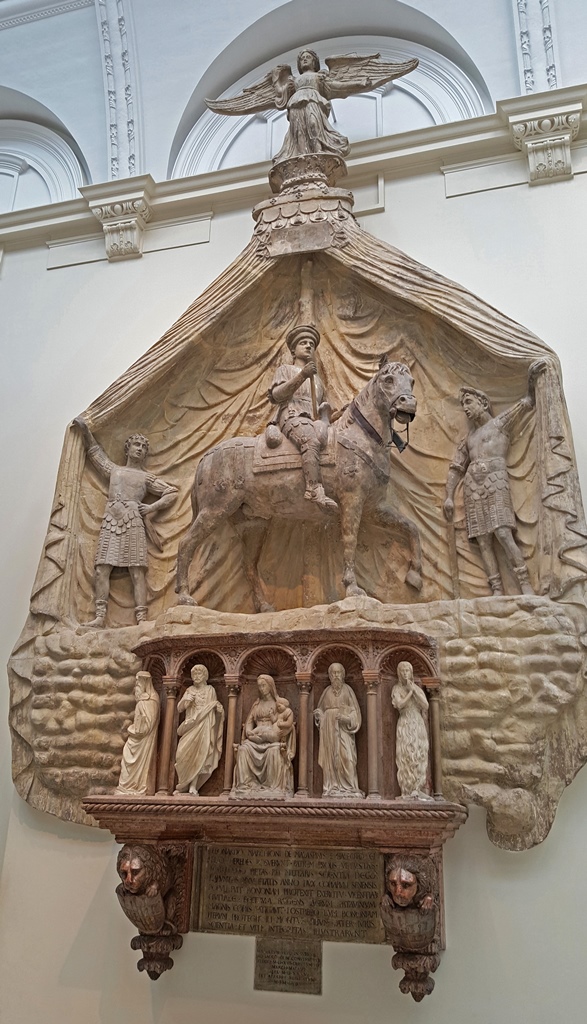

Eventually we found a Hall of Sculpture. The museum is supposed to have an immense

sculpture collection, but we had the feeling there must have been a lot of it somewhere

else, as the hall didn't seem that big. But the sculptures we did see were beautiful.

Here are a few:

Sculpture Hall

Monument of Marchese Spinetta Malaspina, Verona (1430-35)

Choir Screen from 'S-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands (1600-13)

St. John Nepomuk, Burkard Zamels (ca. 1730-40)

The Three Graces, Antonio Canova (1814-17)

Another type of object we kept running into was the altarpiece. Altarpieces have a

purpose, so they would have to be classified as applied art:

Altar and Perpetual Calendar, Gdansk (1625-50)

The Boppard Altarpiece, Strasbourg (ca. 1500-10)

The Troyes Altarpiece, France (ca. 1525)

The St. Margaret Altarpiece, Germany (ca. 1520)

Altarpiece with the Life of the Virgin, Brussels (ca. 1520)

Retable of St. George, Spain (ca. 1410)

Upper Part of an Altarpiece, Italy (1527-33)

Next we entered a large room called the Cast Court, which was filled with sculpture, some of

which we recognized. More to the point, we recognized certain works of art as being somewhere

else. For example, Michelangelo's David is in Florence, Michelangelo's statue of

Moses is in Rome, and Raphael's School of Athens fresco is in Vatican City (and

is part of a wall in the Pope's apartments, and isn't going anywhere). Something wasn't right

here. As turns out, everything in the Cast Court is a copy. The name "Cast Court" refers to

the fact that most of the sculptures are plaster casts of originals located somewhere in

Europe. Some were made for technical or educational purposes, and others were made to furnish

the next-best thing to the originals. The museum commissioned some of them, mostly in the

19th Century, and bought others that had been made by other people. The largest cast is a

copy of Trajan's Column in Rome, which is nearly 100 feet tall. The copy is too tall to fit

in the court, so it was cut in half, with the two parts displayed next to each other. There

are actually two rooms of Casting Court, which were opened in 1873. The rooms were popular at

first, but later fell out of favor with visitors because, well, they're copies. But they've

become more popular of late, as it's undeniably impressive to be surrounded by all of these

works of art at once.

Cast Court

Cast Court

Cast of Moses (Rome), Michelangelo (1513-42)

Cast of Tomb of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza (Rome), Andrea Sansovino (1505-09)

Cast of Tomb of St. Peter Martyr (Milan), Giovanni di Balduccio (1338)

Cast of Pisa Cathedral Pulpit, Giovanni Pisano (1302-10)

Cast of Florence Cathedral Cantoria, Donatello (1433-56)

Cast of Puerta da la Gloria of Santiago de Compostela, Master Mateo (1188)

Cast of Tabernacle in St. Leonard in Zoutleeuw (near Brussels), Cornelis Floris (ca. 1552)

Casts of Tombs, Tabernacle, Trajan's Column

Cast of Western Doors of Aix Cathedral, France (1477-1505)

Cast of Monument of Rudolph von Scherenberg (Würzburg), Tilman Riemenschneider (1496-99)

Cast Court

After leaving the Cast Courts, we discovered a courtyard in the middle of the museum.

There was a café in the corner, and there were unique views of some of the interesting

old buildings that comprise the museum.

Museum Building from John Madejski Garden

We didn't have time to linger, as the museum was threatening to close for the day

shortly. We went back in and found some rooms of Asian art.

Buddhist Shrine and Associated Objects, Burma (1850-80)

Group of Disciples of the Buddha, Hoshinsai Uemura Masanobu

Outer Kimono, Kyoto (1870-90)

Ritual Crown, Nepal (1677)

One area specialized in art from India. One of the items was called "Tippoo's Tiger",

which was made around 1795 for Tipu Sultan, the Muslim leader of the Kingdom of Mysore

in India. Tippoo's Tiger is a mechanical creation which depicts a British soldier

being mauled by a tiger. When activated, one of the soldier's hands moves, a wailing

sound comes from the soldier and a growling sound comes from the tiger.

Durga as Mahisasuramardini, India (ca. 1240-60)

Temple Door Guardian, India (1600-1800)

"Tippoo's Tiger", India (1799)

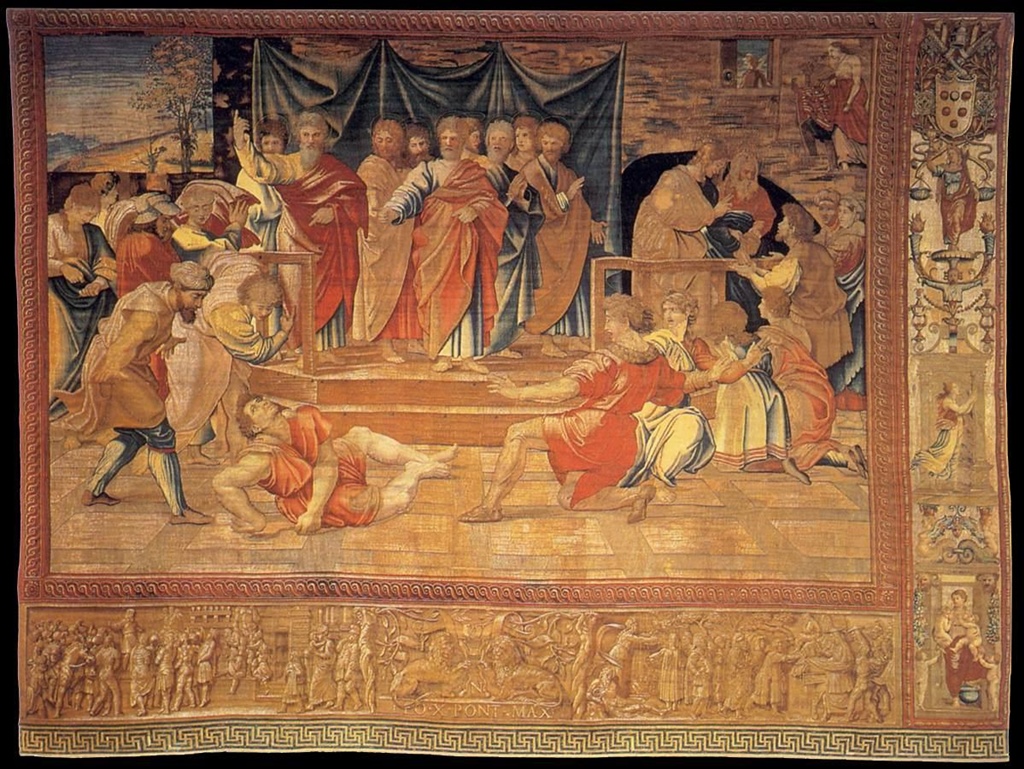

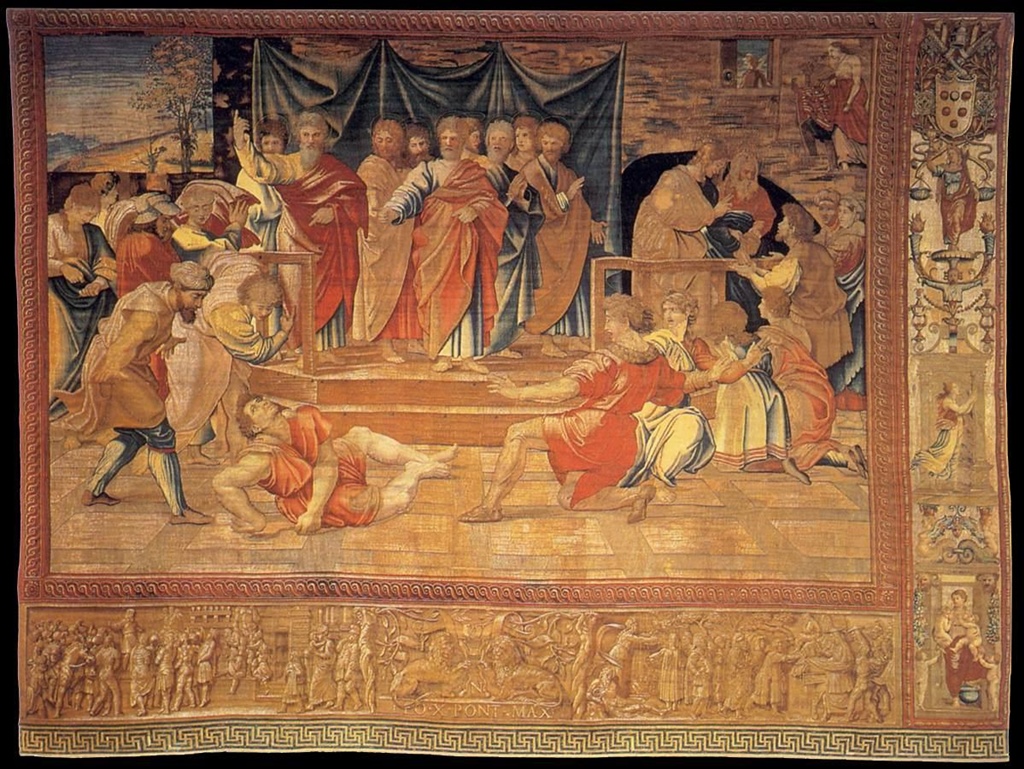

Another room displayed some large, colorful drawings which are known as the Raphael

Cartoons. There are seven of them, and they depict scenes from the Gospels and the Acts

of the Apostles. They are cartoons, meaning they are drawings on paper which are meant

to be used as full-size guides for artwork to be done in another medium. One use of

cartoons is in the production of frescoes, but these were drawn to be used in the

production (in mirror form) of tapestries. The cartoons are part of the British Royal

Collection, but have been on loan to the museum since 1865 from Queen Victoria and her

successor monarchs, currently Queen Elizabeth II.

The Death of Ananias, Raphael (ca. 1515)

The Death of Ananias in Tapestry Form (ca. 1515)

Paul Preaching at Athens, Raphael (ca. 1515)

World Map (facsimile), Martin Waldseemüller (ca. 1507)

After looking at the cartoons, there was an announcement that the museum would be

closing in a half hour. In Europe, all visitors must be physically out of a museum

building by closing time, and there was an entire floor we hadn't looked at yet.

Nella didn't really have the energy to try, so she found a bench to sit on while I

attacked a floor featuring metalwork exhibits. Not too many photos, and even fewer

that came out decently, but here are a few:

Hereford Screen Gate, Sir George Gilbert Scott (1862)

Centerpiece for Golden Jubilee, Alfred Gilbert (1890)

Model of the State Coach, Sir William Chambers (ca. 1760)

We made our way out of the front door with a few minutes to spare, returned to the

Underground station and headed for our hotel. We rested, found dinner and then rested

some more. We had one more day in London, and we were going to spend it at the museum

that is possibly London’s most prestigious - the British Museum.