Charles Bridge and Little Quarter

Prague is the largest city (1.3 million people) in the Czech Republic, and also its capital.

Prague escaped much of the devastation that was inflicted on many European cities during

World War II and retains much of its historical architecture. It’s sometimes called the

“city of spires”, and it does seem to have more than its share. The city is cut in two by

the scenic Vltava River, which flows northward through the city on its way to join the Elbe

(which eventually empties into the North Sea), and there is plenty to see and do on both

banks.

Central Europe

Prague

Prague began as a fortified settlement on the west bank of the river in the 9th Century A.D. The

area was then known as Bohemia, a name which had come from the Boii, a Celtic tribe

which had been the first known tribal inhabitants of the area around 500 B.C. The Boii had been

followed by a Germanic tribe called the Marcomanni in 9 A.D. (the Celts migrated southward),

and then around 512 A.D. by a Slavic tribe known as the Czechs (some of the Marcomanni

joined with another Germanic tribe called the Lombards and migrated south, while others stayed and

assimilated with the Czechs). Bohemia was eventually ruled by a succession of dukes and princes of

a dynasty called the Přemyslids, and after founding Prague, they used it as their center of

operations. One of the 10th Century dukes was Wenceslas I, the “Good King Wenceslas” of the

Christmas carol and now patron saint of the city. Good or not, his reign didn’t end well for him,

as a group of nobles including his younger brother assassinated him in 935. But this did qualify

him for martyrdom and sainthood.

Wenceslas I

Early in the 11th Century, the Bohemian dukes became vassals of the Holy Roman Empire, which in

1085 bestowed upon Bohemia the status of being a kingdom, with its first king being Vratislaus I

(who had been Prince Vratislaus II of the Přemyslid line). The throne at first was not a

hereditary one, but became one about a century later. The throne of the Holy Roman Empire also

wasn’t hereditary, and Bohemian King Ottokar II attempted to gain the imperial throne in 1278.

But he lost the Battle on the Marchfeld (and his life in the process) to Rudolf I, the first

German king in the Habsburg dynasty (Rudolf was not able to gain the imperial crown due to

French political maneuvering).

The Přemyslid dynasty ended in 1306 with the death without heir of Wenceslaus III at the age of

16 (like Wenceslaus I, he was murdered). But Wenceslaus had a sister named Elizabeth, who

married John, son of Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII in 1310. John was only 14 at the time, but

his followers were able to secure the Bohemian throne for him by deposing the reigning king.

John was the first Bohemian king from the House of Luxembourg, but he was not the last, as he

and Elizabeth were able to produce an heir named Charles in 1316. John had ambitions of

following his father to the imperial throne, but the prince-electors who selected the emperor

voted for a Bavarian duke instead. The Bavarian didn’t live forever, dying in 1347, but John

had unfortunately died first, in 1346 at the Battle of Crécy in France. Charles, however, was

30 years old by this time and succeeded his father as King of Bohemia. He spent the next few

years expanding his kingdom and consolidating his power, and in 1355 he was crowned Holy Roman

Emperor Charles IV, basically without opposition. Charles was the first Bohemian emperor, and

chose to use Prague as his base of operations. To make the city more suitable as the center

of an empire, he spent a lot of money largely rebuilding it, using 14th Century Paris as a

model. A lot of his handiwork still exists, and you’ll be seeing some of it in pages to come.

Charles IV

Around this time, a period of religious conflict in Europe had its beginnings, and Prague

and Bohemia were at its forefront. In Prague, a priest named Jan Hus, influenced by the

writings of an Englishman named John Wycliffe and anti-papal views taught to him by some

of his professors at the University of Prague, took to preaching ferociously about corruption

in the Catholic Church. One of his primary targets was the church’s sale of “indulgences”,

by which someone could give a church representative money to shorten a deceased ancestor’s

time in purgatory (and presumably to release him or her to heaven). If this sounds familiar,

it might be because this is one of the main issues that would be hit by Martin Luther a

hundred years later. Hus struck a nerve with the Bohemian populace, eventually speaking to

large, enthusiastic crowds and catching the notice of the higher-ups in the church. He

received warnings to cut it out, but ignored them. In 1414, Sigismund of Hungary, the head

of the Holy Roman Empire (but not crowned emperor yet) convened a council in the city of

Konstanz in southern Germany, where the church and Hus would be able to air their differences.

Sigismund gave Hus a promise of safe conduct, but this turned out to be wishful thinking. Hus

was arrested and tried for heresy after some preliminary discussions, and Sigismund was told

that promises to heretics didn’t count. In June of 1415 Hus was burned at the stake after

refusing to renounce his statements.

Jan Hus

Back in Bohemia, people were outraged and moved strongly away from Papal teachings. Rome didn’t

stand for this and organized a crusade against them. But the Bohemians were ready for this and

were able to defeat the crusade. Three more crusades followed (collectively referred to as the

Hussite Wars), and the Bohemians repulsed them each time. At this point, negotiations were

initiated and a compromise was reached which allowed Bohemia to practice its own version of

Christianity, a version that proved to be very popular during an uneasy truce until tensions

reached a boiling point again in 1618. At this time, hard-line Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II

was trying to impose religious uniformity (standard Roman Catholicism) on everyone in the

empire. In a meeting at the Bohemian Chancellory in Prague, some of the emperor’s

representatives, who had presented a threatening letter declaring Protestant lives to be

forfeit, were bodily thrown out of the Chancellory window in an event known as the

Defenestration of Prague. The representatives survived the 70-foot fall as it turned

out – Catholics maintain they were saved by angels, and Protestants say they were cushioned by

a dung heap.

The Defenestration of Prague

Regardless, the emperor wasn’t even slightly amused, and he sent an army to teach the Bohemians

a lesson. First, the Bohemian army was crushed in the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, and

then mass executions of Bohemian aristocrats were undertaken.

Prague Executions, 1621

Protestant states from across Europe were outraged by the Catholic atrocities and sent their own

armies, and the Thirty Years’ War was underway. Between the violence, famine and plague, this

war resulted in the death of eight million people. The war also pretty much spelled the end of

Protestantism in Bohemia. Even today, the religious community in Prague is overwhelmingly

Catholic. But even so, Jan Hus is still considered a national hero, and there is an impressive

monument to him in Prague’s Old Town Square.

Jan Hus Monument, Old Town Square (1915)

In addition to losing its religion, Bohemia lost most of its autonomy following the Battle of

White Mountain, with Habsburg emperors keeping them on a short leash for many years. During these

years, German became the semi-official language in the cities (including Prague), with Czech

mainly being spoken in rural areas. When the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806 after being

defeated by Napoleon in the Battle of Austerlitz, Bohemia ended up in the new Austro-Hungarian

Empire, as part of Austria. Like Hungary, Bohemia pushed for more autonomy in the new empire, but

unlike Hungary, Bohemia never achieved this goal. This had to wait until the end of World War I

in 1918, when Austria-Hungary ceased to exist. At this time, Austria and Hungary continued to

exist as independent countries, but lost a great deal of territory to existing countries and to

newly-formed ones, including the First Czechoslovak Republic, which was mostly created from the

Austrian regions of Bohemia and Moravia-Silesia and the Hungarian region of Slovakia.

Prague Celebrating Independence from Austria-Hungary

Czechoslovakia Before World War II

Though both the Czechs and the Slovaks were undoubtedly happy to be liberated from Austria-Hungary,

there was a certain amount of friction between them. Clearly there were ethnic and linguistic

differences, but mostly the Slovaks must have felt underrepresented, as they were outnumbered by

the Czechs two-to-one. But by 1938, both groups had much more to worry about, as they had caught

the covetous eye of Adolf Hitler. Over in Bohemia, the Czech language had largely returned to the

cities, and the German-speakers were mostly in the border areas of the new Czechoslovakia. Hitler

was threatening to start a war in Europe, but promised to behave himself if the German-speaking

areas of Czechoslovakia, referred to as the Sudetenland, were turned over to Nazi Germany.

Negotiations were begun between Germany, France, Britain and Italy (and nobody from Czechoslovakia),

and Hitler’s terms were agreed to (in something called the Munich Agreement), as Britain and France

still remembered the horrors of World War I, and wanted to avoid a repeat at all cost. The Czechs

and Slovaks understandably considered this to be a betrayal, but there wasn’t much they could do

against the diplomatic and military pressure arrayed against them. Of course this attempted act of

appeasement failed, and Hitler swallowed up the rest of the country within a few months. By

September of 1939, Hitler had invaded Poland, and World War II was underway.

Hitler Visiting Prague Castle, 1939

The Nazis, of course, were the worst occupiers imaginable. They sent virtually all the Jews

(and a good number of other Czechs) to concentration camps, stole everything that wasn’t nailed

down and responded to any attempts at resistance with horrible atrocities. Czechoslovakia was

eventually liberated from the Germans by George Patton from the west and the Red Army from the

east. The country was reconstituted (there had been a “government-in-exile”, which helped) and

was again a republic. Not being pleased with the treatment they’d received during the war,

they expelled nearly all the German-speakers (who had mostly been Nazi sympathizers) from the

country and formed a government which was generally favorable to the Soviet Union (no doubt

remembering their betrayal at the hands of France and Britain). The largest of the political

parties was the Communist Party, which at an opportune moment in 1948 staged a coup d'état and

installed a single-party, authoritarian, pro-Soviet government. With the help of the Soviets,

they trained their secret police, the Státní bezpečnost (“State Security”), or StB, in

methods of spying and extracting information and confessions from prisoners, and in keeping

Czechoslovak citizens from defecting to the west. It didn’t take long for the Czechoslovak

citizenry to figure out that the west maybe wasn’t so bad after all, but by then they were

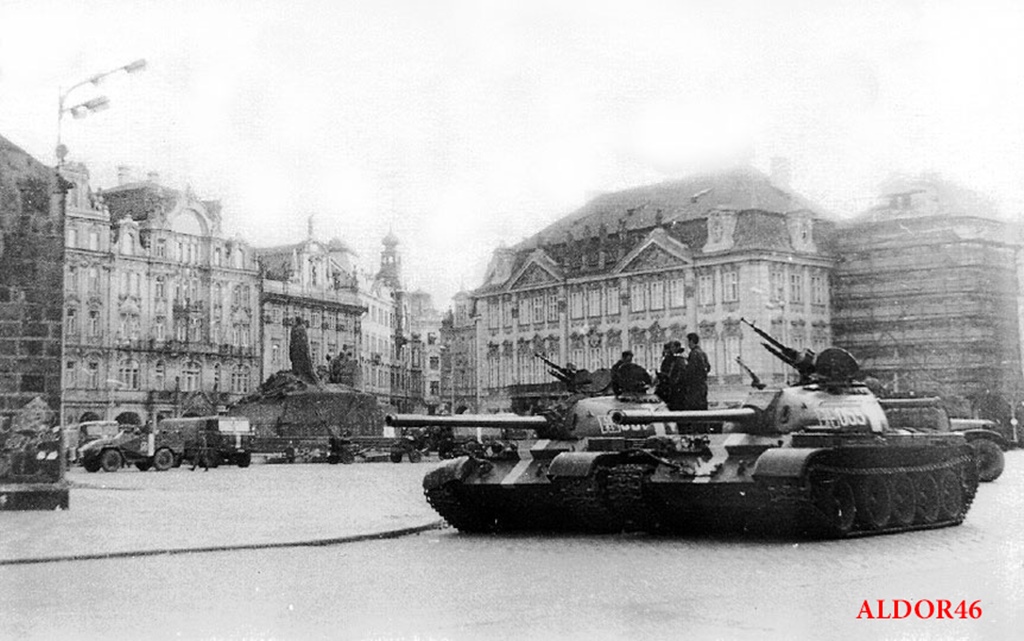

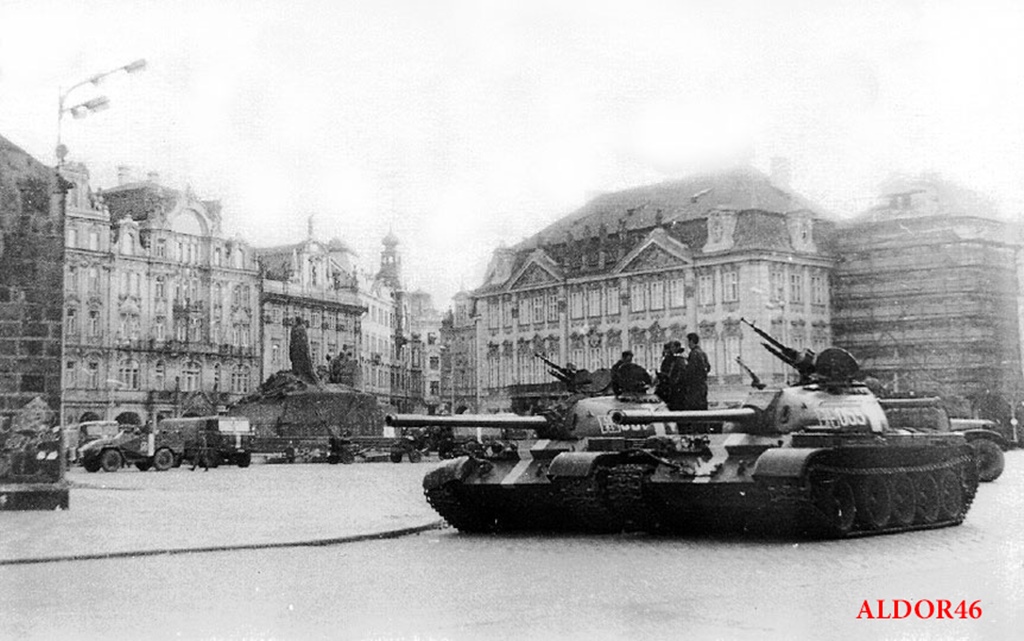

pretty much stuck. In 1968, a man named Alexander Dubček became the party’s First Secretary,

and he started to implement some reforms, including decentralization of the economy and

democratization, while loosening restrictions on speech, media and travel. The Soviets, under

Leonid Brezhnev, were appalled by these developments and tried to talk the Czechoslovak

leadership into reversing them. When this didn’t work, they organized an invasion of the

country, along with forces from Warsaw Pact countries Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary, and

occupied Czechoslovakia with 200,000 troops and 2,000 tanks.

Soviet Tanks in Old Town Square, 1968

Dubček encouraged the citizenry to not resist, and most people didn’t, as the odds against them

were obvious. Dubček was allowed to remain in his post and to temporarily keep some of the reforms

in place, in order to defuse possible protests, but in 1969 he was removed and replaced with a

hard-liner who reversed all of the reforms.

Things stayed this way for several years, but in 1989, Glasnost (openness) and

Perestroika (restructuring) were in the air, courtesy of Soviet General Secretary Mikhail

Gorbachev, and the Warsaw Pact was crumbling. Authoritarian governments were being removed right

and left, not always peacefully. Prague citizens decided it was time to try their luck again, and

in a series of gigantic demonstrations now referred to as the Velvet Revolution, the Communist

government was persuaded to step aside and allow a non-Communist government to be installed.

Playwright and human rights activist Václav Havel was elected President and successfully negotiated

the removal of Soviet troops from the country by early 1990. By popular agreement, the economy was

transformed into a market economy, but again it didn’t take long for disagreements to surface

between the Czechs and the Slovaks. In 1992, discussions began on a breakup of the country into

two, and agreement on the details was eventually reached. The split took effect on January 1, 1993,

when the Czech Republic and Slovakia were created. This event is referred to as the Velvet Divorce.

Reactions at the time were mixed, among both Czechs and Slovaks, who would've liked a chance to vote

on it. Havel was opposed to the breakup, and resigned so he wouldn’t have to preside over it.

Opinions remain mixed to the present day, but at this point it’s pretty much just a fact of life.

We were looking forward to visiting this history-laden place, but to get there we first had to leave

London, another history-laden place. Our flight to Prague was to leave from Stansted Airport, which

we’d never heard of before making the reservation. Stansted turned out to be 42 miles northeast of

central London, reachable by taxi for the wealthy or for the rest of us via a train called the

Stansted Express that leaves every fifteen minutes from the Liverpool Street station. Stansted

Airfield was used during World War II for the launching of bombing raids, and immediately after the

war was used for housing German prisoners of war. Today, after many improvements, it is mostly used

by lower-cost airlines, such as easyJet, which flew us across the English Channel and much of

continental Europe to Prague’s Václav Havel Airport.

Stansted Airport

Stansted Airport and Surrounding Countryside

On arriving at Prague Airport, we immediately looked for an ATM. While Slovakia elected to go with

the Euro beginning in 2009, the Czech Republic decided to stay with their own currency, the Czech

koruna. The symbol for Czech korunas is Kč, and at the time of our trip, a koruna was worth

about 4.3¢ in U.S. money. Euros are pretty easy to find in the U.S. (though the exchange rates are

usually horrible), but korunas are more of a challenge, so we decided we would just visit an ATM as

soon as we got into the country. Fortunately for us the ATM was easy to find, as we needed the

cash right away. Not much of it, though, as we’d decided to try getting into town using the

ultra-cheap method: the Metro. Using the Metro in Prague is very inexpensive, but there’s one

problem – it doesn’t go all the way to the airport. You need to take a bus from the airport to get

to the Metro, and then the Metro takes you the rest of the way into town. Simple in concept, but

less simple when you’re loaded down with luggage and the bus isn’t designed for passengers with a

lot of luggage. Usually an airport bus will have a section where everyone can leave their luggage,

but this bus did not for some reason. So there was luggage in the aisle, on people’s laps and

shoehorned in where people would normally try to put their feet, and the bus ride was less than

comfortable. And then we had to drag all of our luggage down into the Metro tunnel and onto the

train, but this part was about what we’d expected. We’d done some research beforehand, and we got

off at a stop we knew to be just down the street from our hotel. Total fare: 32 Kč apiece, or

$1.34 in U.S. money. Our research also included a look at Google Maps Street View, which we’d used

to figure out exactly how to get from the station to the hotel, which wasn’t as straightforward as

one might expect. The station was in a complicated intersection where the streets weren’t marked

very well, and the entrance to our hotel, the Hotel Liberty, consisted of a door sandwiched between

two stores. But knowing what to expect, we found the hotel, checked in and took a much-needed rest.

Hotel Liberty

Bob in Hotel Room

One of the difficulties of visiting Prague (Praha in Czech, pronounced about how it looks)

is dealing to some extent with the language. Not really to speak it or understand someone else

speaking it, though – the Czechs know their language is a challenge for foreigners, and nearly

everyone in the tourist-visited areas knows some English. But not totally everyone, and there is

some signage you might have to figure out. Czech is a Slavic language, like Russian, Polish,

Slovak, Bulgarian and others, so if your experience with foreign languages is limited to Romance

or Germanic languages, you’ll probably feel pretty lost at first. The basic vocabulary, the

grammar and even the alphabet don’t quite match up. But things could be worse: there are a lot

of international words (like newish products or technological terminology) which are similar

everywhere, and Czech, considered a Western Slavic language (like Slovak and Polish), at least

uses an alphabet which uses the western Roman alphabet as a starting point. In other words, the

Czech alphabet, unlike the Russian alphabet, is not based on Cyrillic. It does have some funny

marks on a lot of the letters, though. These came from the same need that were satisfied by the

Cyrillic alphabets – the need to represent in writing the sounds commonly coming out of

conversing Slavs, for which the standard Latin alphabet is not well suited. For example, the

“zh” sound, like the “s” in “measure”, can be represented as “zh”. But the Cyrillic alphabet

was created in the 9th Century for Slavs who didn’t have a written language, and creating

different sounds with somewhat arbitrary combinations of letters would have created a level of

complexity that might have discouraged the alphabet’s use. So, for instance, in Russian, the

“zh” sound is represented as the single letter Ж, while in Czech, it’s represented as Ž (the

thing over the Z is called a háček). Here are some letters and pronunciations you

might not expect:

- ě – ye as in “yeti”

- c – ts as in “its”, č – ch as in “cheesy”

- s – s as in “salad”, š – sh as in “shingle”

- r – r as in “reindeer”, ř – rzh as in “Dvořák”

- z – z as in “Zorro”, ž – zh as in “measure”

- u – u as in “put”, ů – oo as in “poodle”

- j – j as in “Jägermeister”

- n – n as in “Nefertiti”, ň – ny as in “canyon”

Most of the pronunciations are pretty consistent, and with a little practice they become less

difficult. Grammar-wise, though, things get ugly pretty quickly. You might be familiar with

languages that have genders for all their nouns (“la mesa” vs. “el burrito”),

but the Slavic languages add a third gender, so there are masculine, feminine and neuter nouns

(German also does this). Also, some languages have the concept of case, in which

different endings are applied to nouns and their adjectives, depending on how the noun is used

(subject, direct object, indirect object, etc.). Endings depend on both the case and the

gender, and you just have to know them. To go with its three genders, German has four

different cases. Czech has seven. Don’t get into the grammar if you don’t have to.

After resting for a while, we went out in search of food. Our hotel was located at the bottom

of Wenceslaus Square. Wenceslaus Square isn’t so much a square as a long, wide street which

is partly pedestrianized. It’s lined on both sides by some interesting old buildings in the

art nouveau and art deco styles, and there is plenty of night life, with

restaurants, shops and drinking establishments. The street climbs gradually to a large domed

building at the top which is currently home to the National Museum. Wenceslaus Square is also

a gathering point for celebrations and demonstrations, and played a big role in the Velvet

Revolution in 1989.

Wenceslas Square

We stood at the bottom of the square and noticed some stands that were selling street food that

looked and smelled delicious.

Sausage Stand, Wenceslas Square

Roasted Pig, Wenceslas Square

We were looking for something more substantial, though, and we ended up in an Italian restaurant,

if I remember correctly. We headed back to the hotel, which looked nicer with the lights on.

Hotel Liberty

We were pretty tired after the day’s exertions and went right to sleep. But tired or not,

our plans for the next day were ambitious. We were going to start with a visit to the

Infant of Prague.