Museum Entrance

Milan's Leonardo Museum isn't really called the "Leonardo Museum". It's called the

Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci

(opened in 1953), and is less about da Vinci than you might expect. It's more a museum

of science and technology (hence the name), in the vein of Munich's Deutsches Museum

or Berlin's Deutsches Technikmuseum.

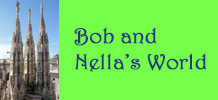

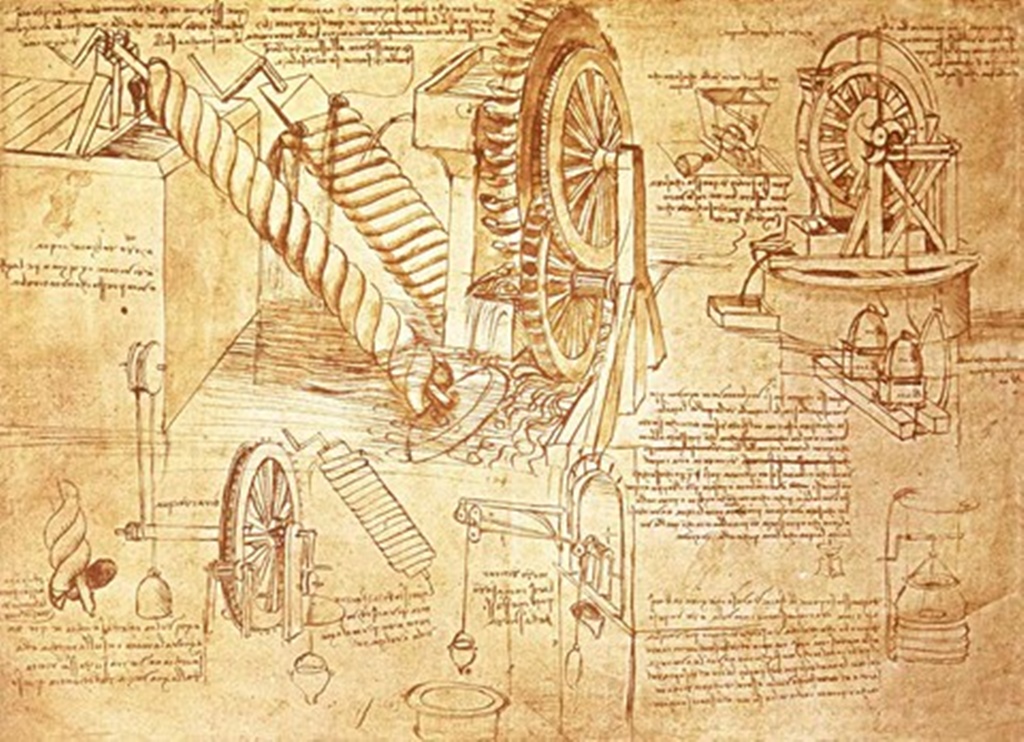

Leonardo, of course, was the original Renaissance Man, and in addition

to his artistic accomplishments, had an insatiable curiosity about the world and how it

worked. His writings were full of drawings and discussions of things found in the natural

world, as well as of designs and contraptions that (for the most part) never came into

existence except in his fertile imagination.

A Page from the Codex Atlanticus

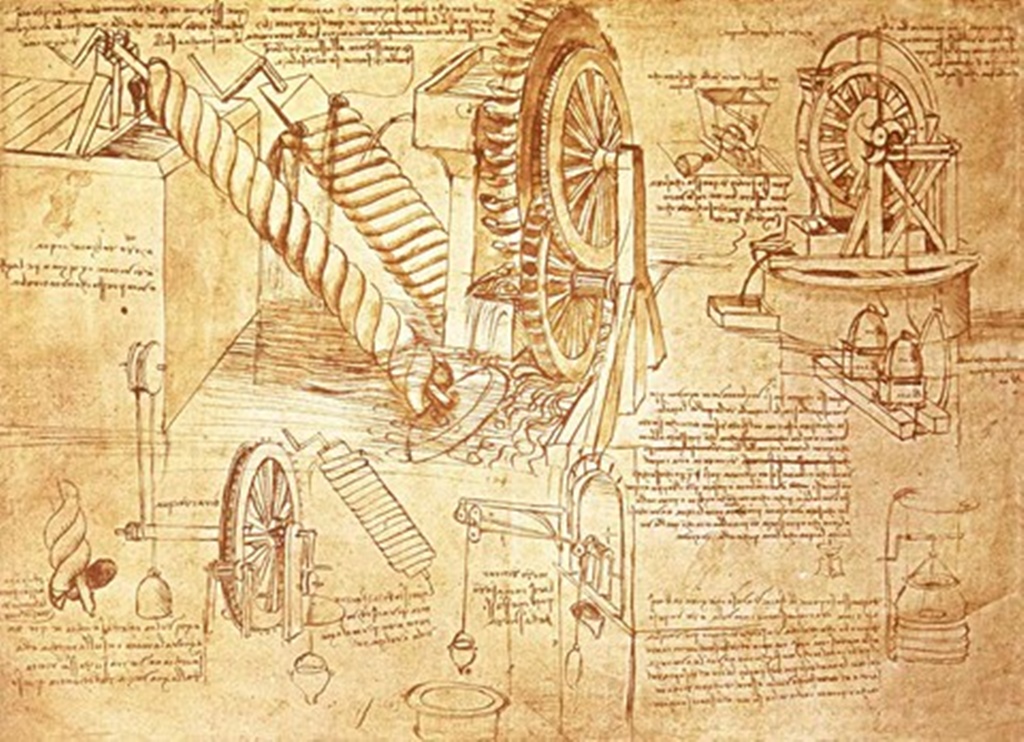

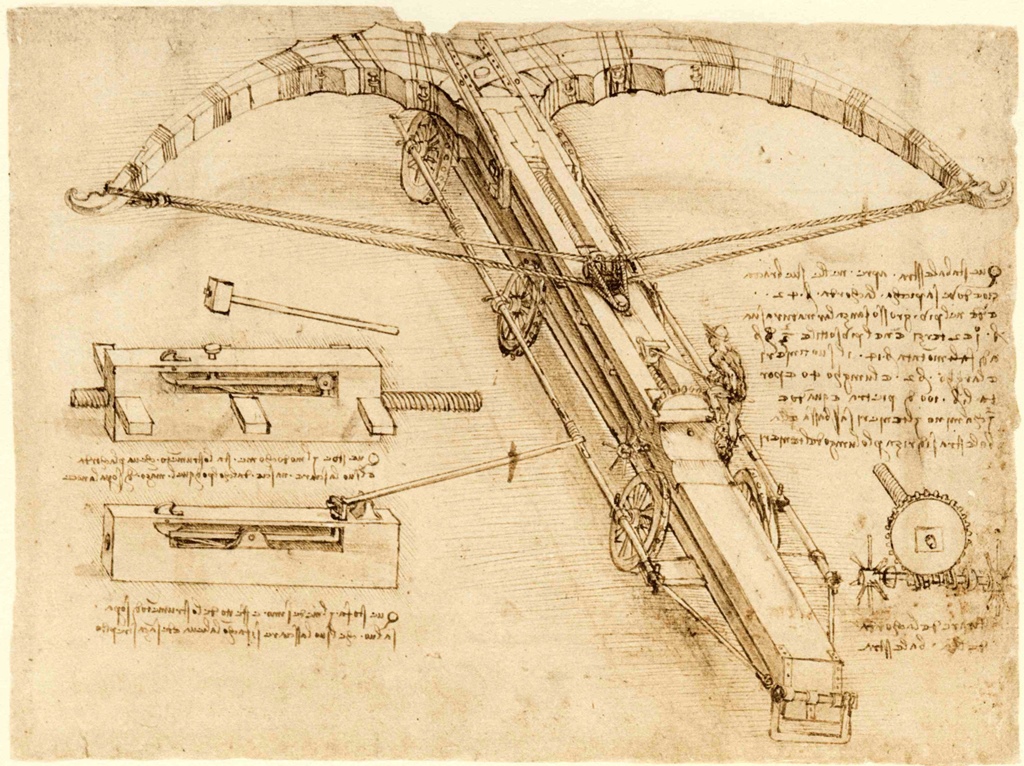

Giant Crossbow from Codex Atlanticus

Where Leonardo da Vinci is concerned, this last aspect is the focus of the museum – the aspect

of Leonardo the Engineer. And of course a lot of stuff that has nothing to do with Leonardo

da Vinci.

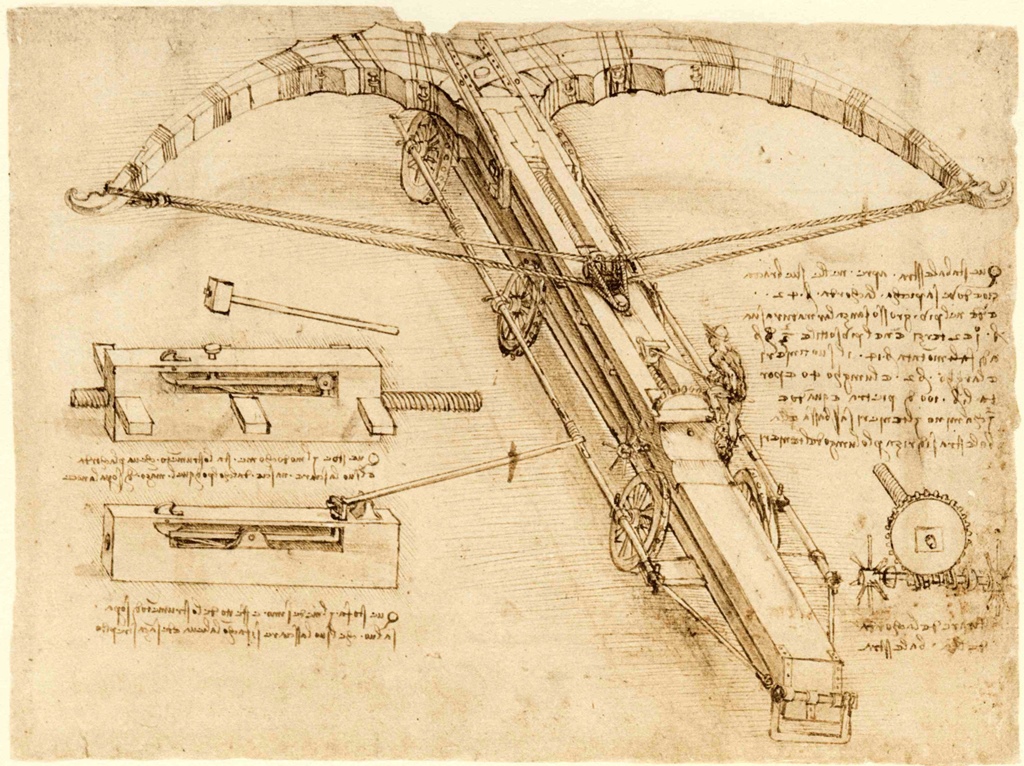

The Leonardo Museum is located a few blocks south of the

Santa Maria delle Grazie

convent, where da Vinci's Last Supper can be found holding dominion over the dining

hall.

Central Milan

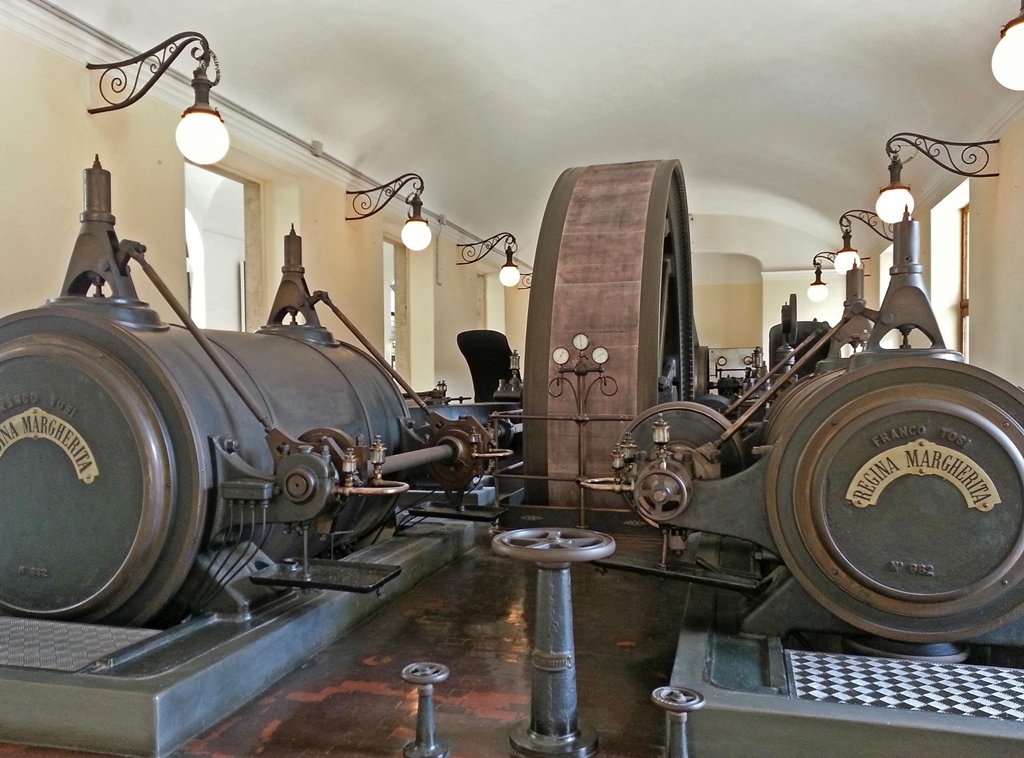

But this is a different kind of place, and this fact becomes obvious right away, as

the entry hall is filled with the Regina Margherita Thermal Power Station, an immense

pile of machinery that was used to create electricity from steam when it was brought

on line in 1895.

Regina Margherita Thermal Power Station (1895)

After getting past the Power Station (complete with imposing Frankenstein switches), we

found ourselves asking what this had to do with Leonardo da Vinci (the answer, of course,

was "nothing"), but continuing onward, we found ourselves confronted with a painting of

The Last Supper. Obviously this wasn't THE Last Supper – in fact it was

done by a different artist, more than a century after da Vinci finished his painting – but

just as obviously, it was heavily influenced by Leonardo's work.

Nella and The Last Supper, Fiammenghino (1626)

This brought up another question – what does this have to do with science and technology?

Again, the answer was "nothing", but it did serve, sort of, as an introduction to an

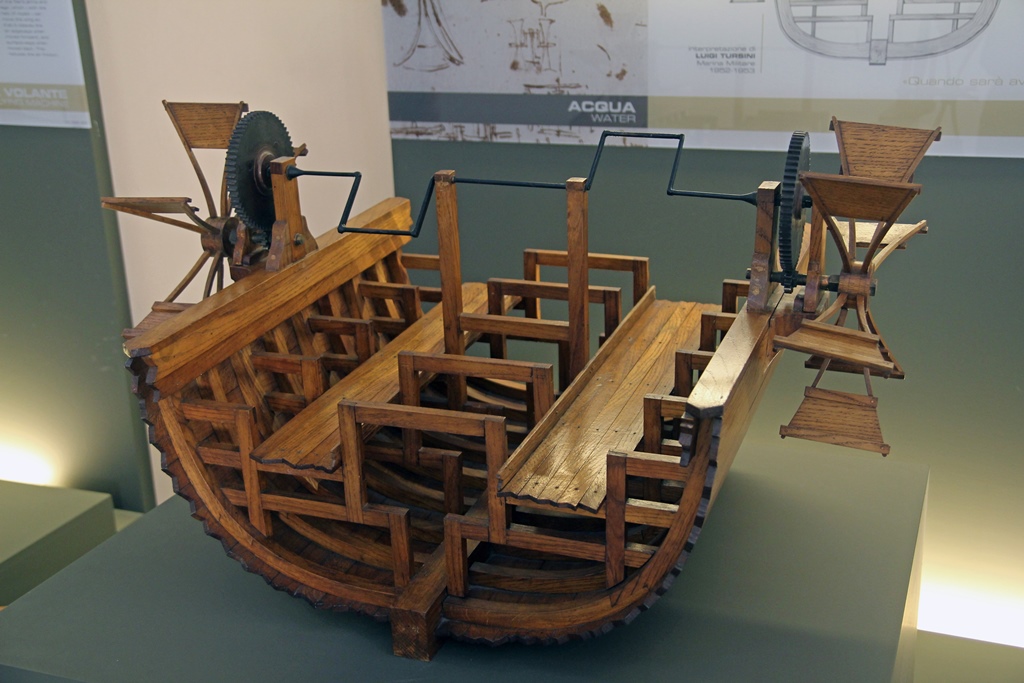

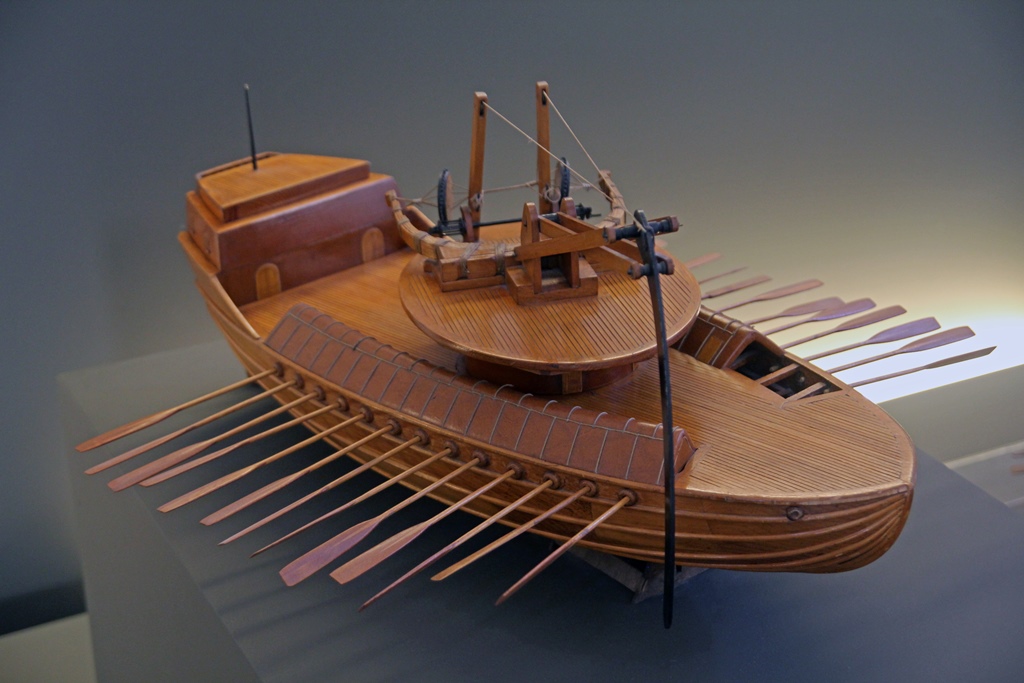

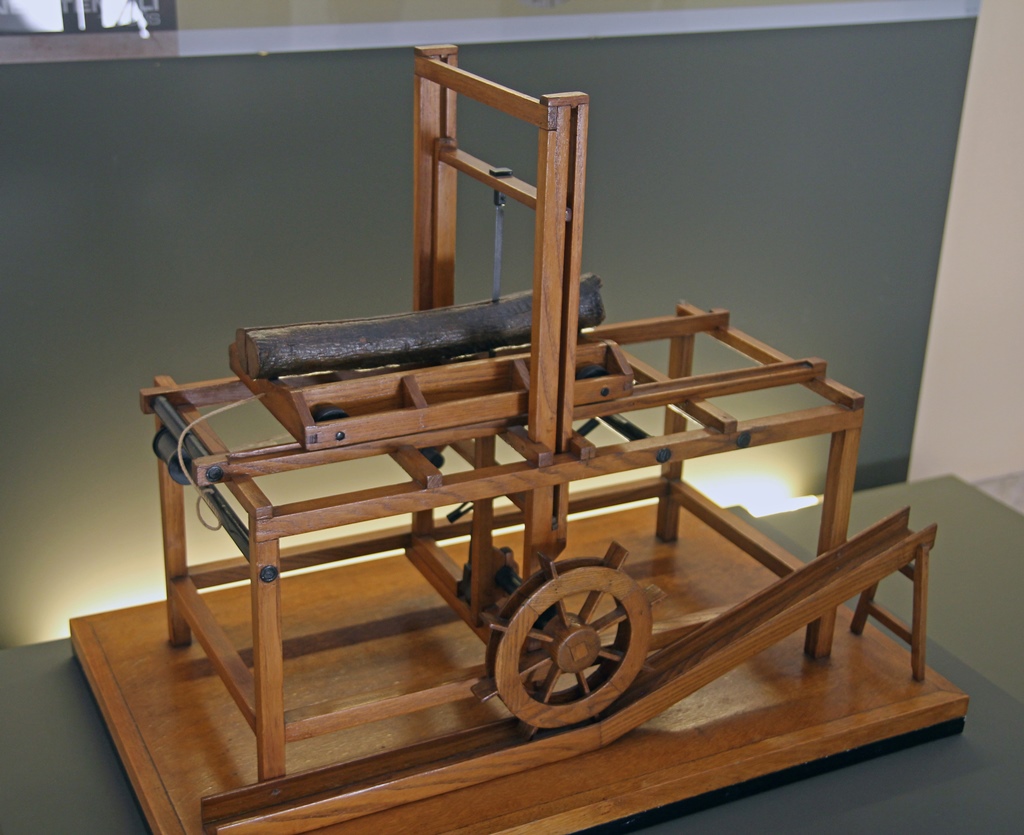

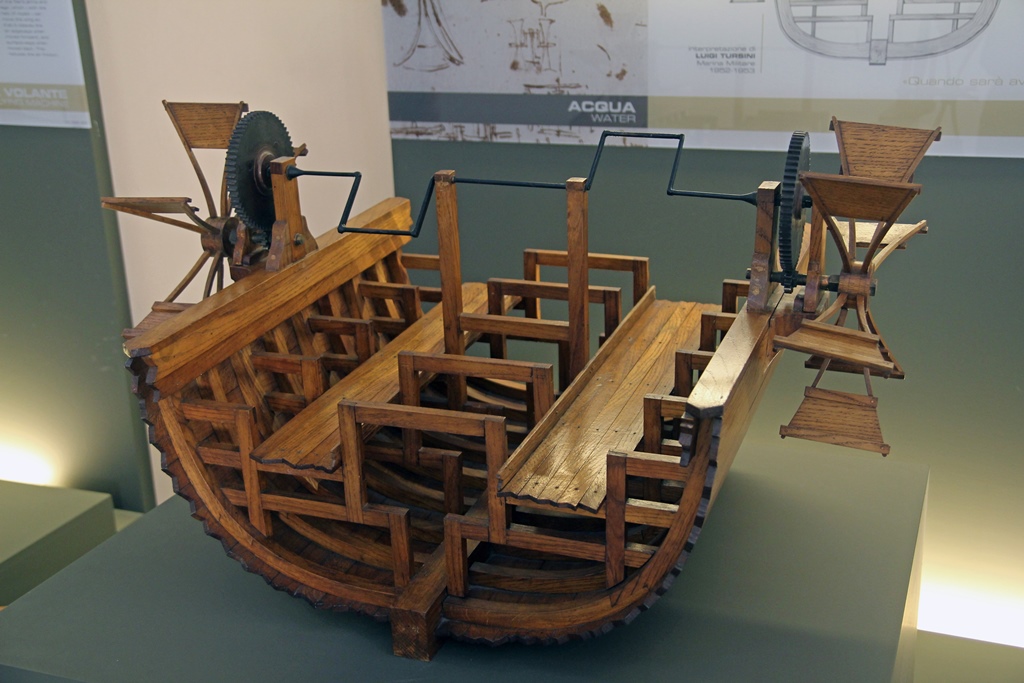

exhibit hall devoted to Leonardo. This hall held a large collection of wooden models of

some of the creations found in Leonardo's notebooks. The museum has a collection of more

than 130 of these models, mainly produced in the 1950's. Not all of the models were on

display, but the ones we could see were fascinating to look at –the three-dimensional

realizations made it easier to understand how they were supposed to work. Here are a few

of them:

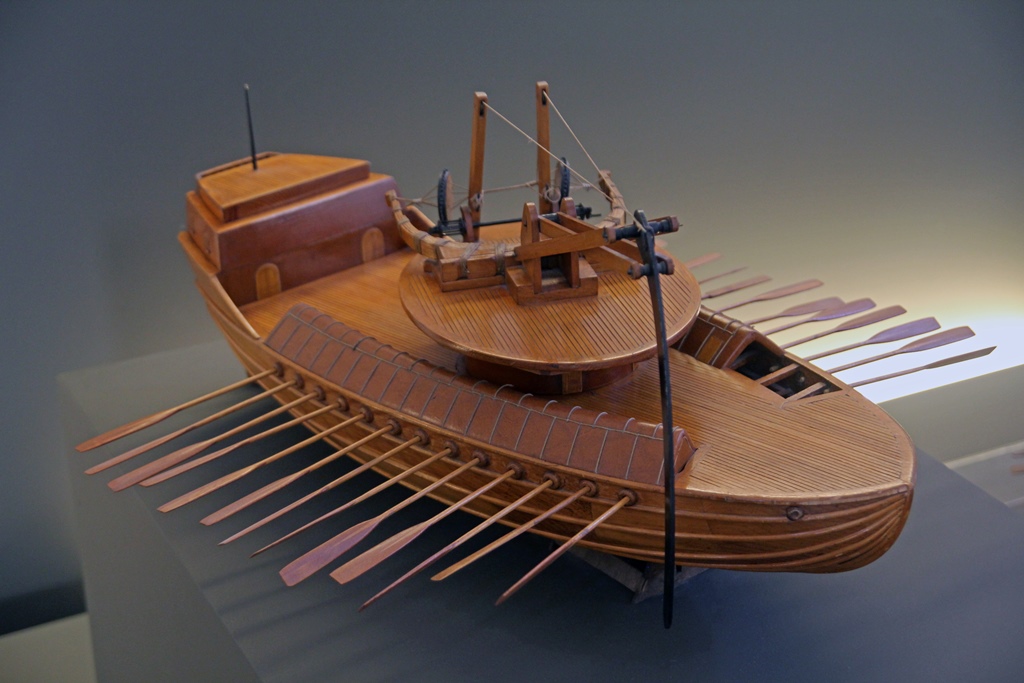

Model of Paddlewheel Boat

Model of Parabolic Swinging Bridge

Model of Mobile Ram Boat

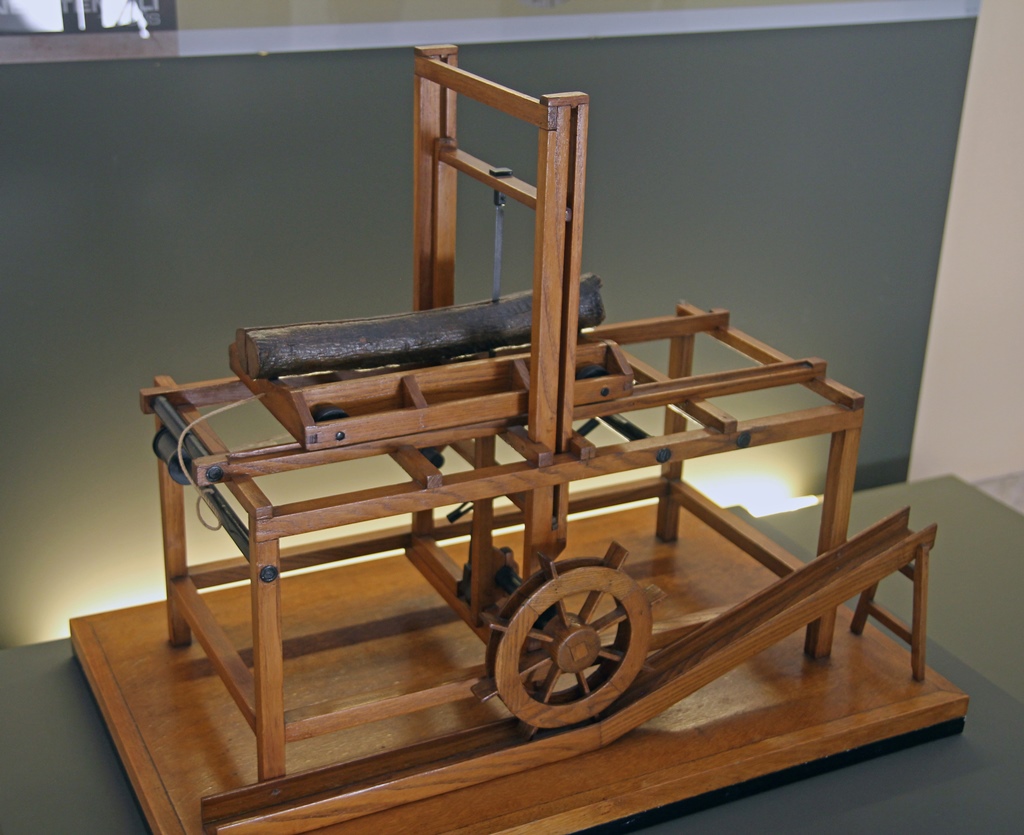

Model of Hydraulic Saw

This exhibit hall brought the Leonardo part of the museum to an end, leaving the rest

of the museum to pure science and technology (apparently the museum has added a new

Leonardo Gallery since our visit; maybe it's larger). One of the first exhibits we came

across was a musical instrument exhibit. Here are some instruments that were made

between the 18th and the 20th Centuries:

18th-20th Century Musical Instruments

Hurdy-Gurdy (1750)

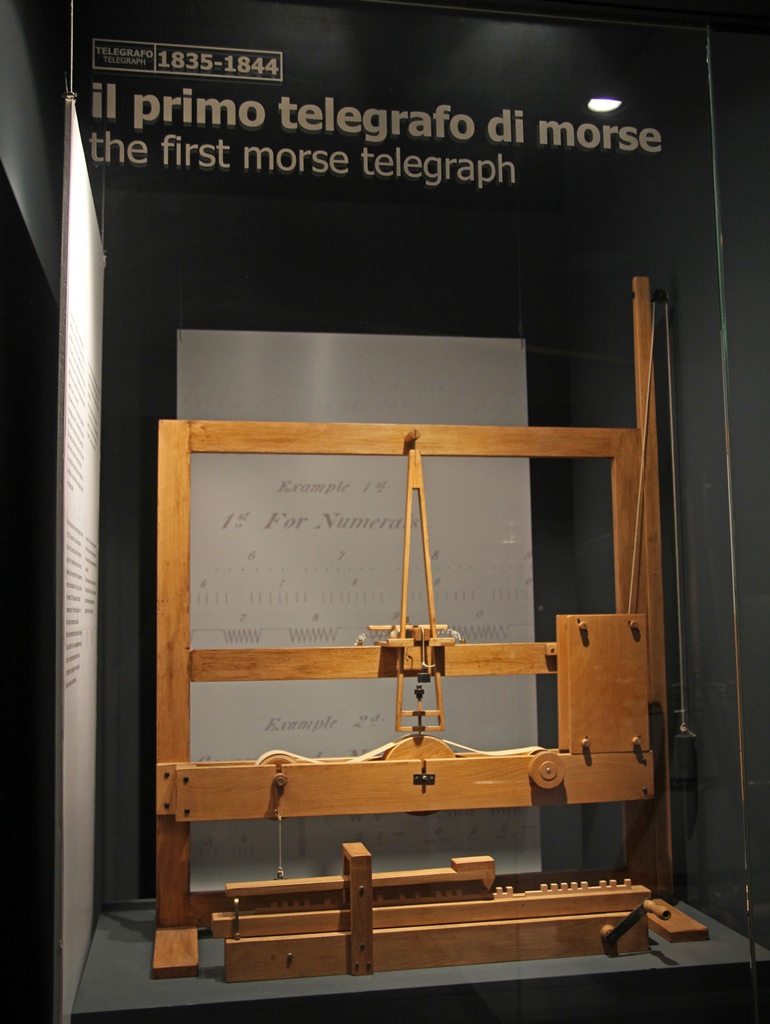

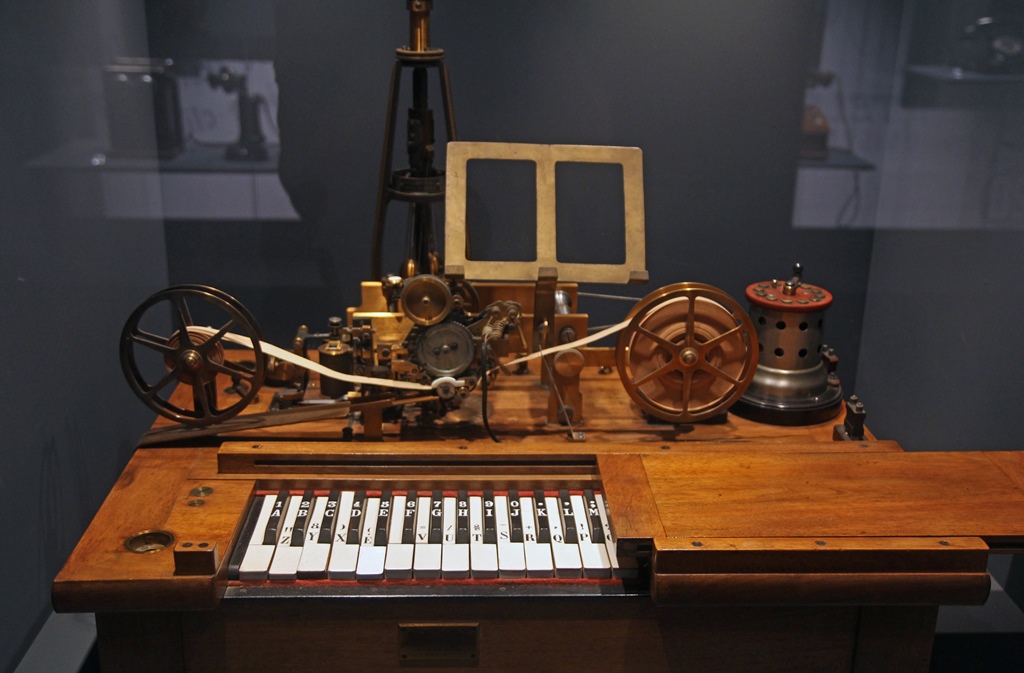

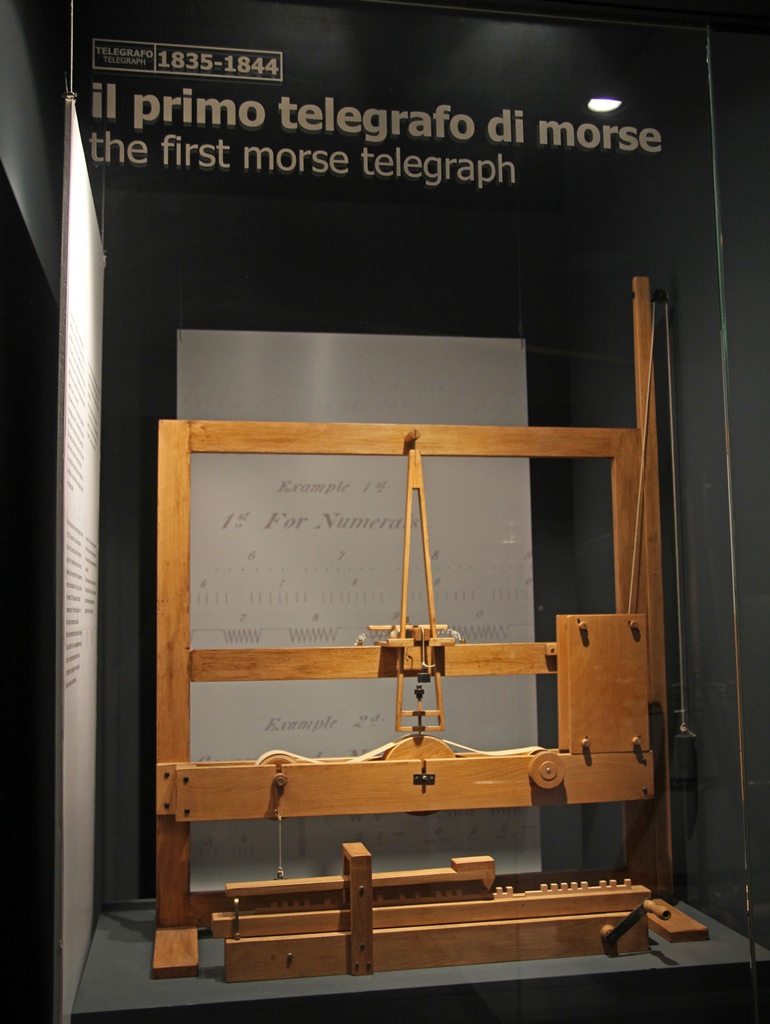

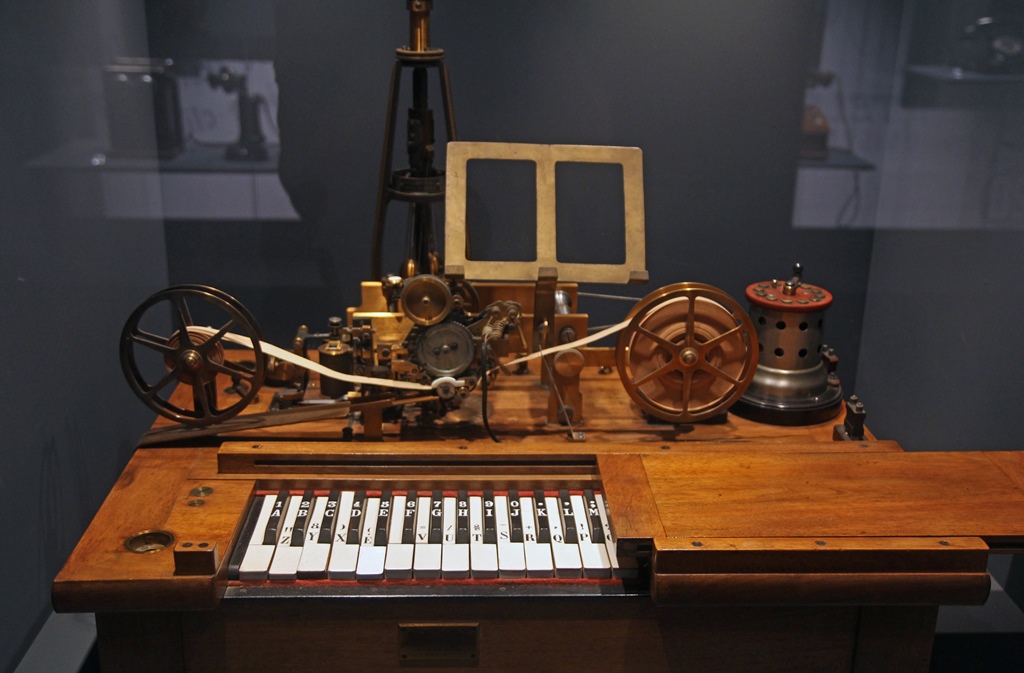

In a part of the museum devoted to communications, some 19th Century telegraph

equipment was on display. There was a model of the original telegraph machine

developed by Samuel F.B. Morse in the 1830's, and there was an actual Hughes printing

telegraph machine that came a few decades later. The Hughes machine sported a few

innovations. Incoming messages were printed on paper tape, making manual

transcription unnecessary, and outgoing messages were put together using a piano-style

keyboard instead of by tapping Morse code with a telegraph key.

Model of First Morse Telegraph

Hughes' Printing Telegraph Model 4

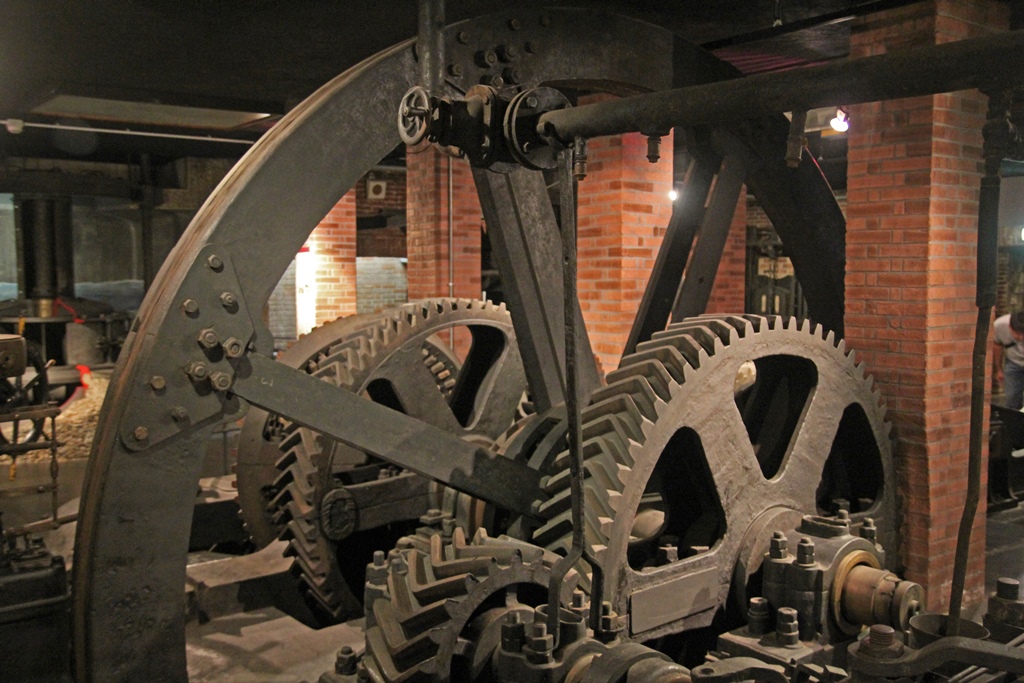

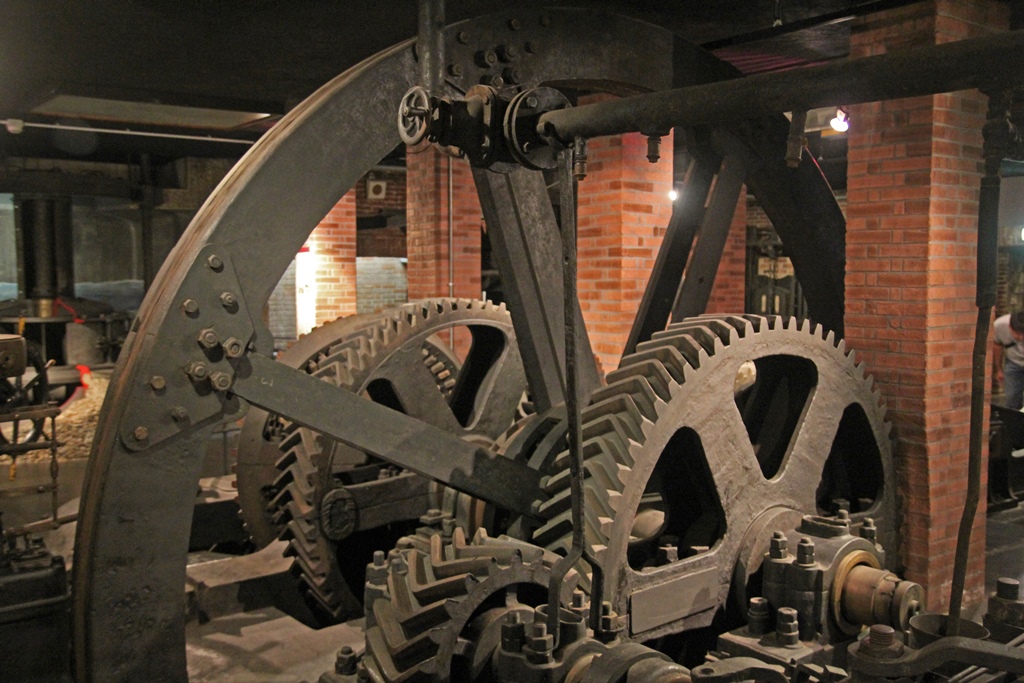

There were a great many additional exhibits in the museum's main building, including

some which were fairly large in scale. Here are a few that were used in industrial

applications in the 19th and 20th Centuries:

Rolling Mill (for Steel Work)

Thomas Horn Steam Engine (ca. 1850)

Francis Turbine (early 20th C., used in Power Generation)

The museum also includes some additional buildings. One such building is devoted to

railroad exhibits:

Railroad Shed

Steam Locomotives (1900)

Steam Locomotive (1923)

Omnibus

Outdoors, between the buildings, there are a few large exhibits. A particularly impressive

one is the Enrico Toti submarine, across from the rail shed. This submarine was

launched in 1967 and saw service in the Mediterranean until its decommissioning in 1992.

It's 151 feet long, with a beam of 15 feet and a draft of 19 feet, and held a crew of 26.

Its diesel-electric drive could move the boat at a speed of 14 knots surfaced and 15 knots

submerged. The submarine gave its name to a class of Italian submarines – three additional

Toti-class submarines were built, and all have been retired. It's possible to join small

guided tours of the submarine, but this involves the purchase of a separate ticket.

Nella and Enrico Toti Submarine (1967)

Enrico Toti Submarine (Stern View)

A quick look at a map of Milan brings up the obvious fact that Milan isn't near any

significant bodies of water, and certainly nowhere near any Mediterranean ports. So you may

be asking yourself how a 150-foot submarine could possibly have surfaced in Milan. You

might be expecting this to have been a challenging operation, and it was. In 2001 the

submarine was brought west from the Adriatic Sea via the Po River, which it entered at Porto

Viro, south of Venice. The Toti was towed up the Po to the city of Cremona, a

distance well above 200 kilometers. Then it was prepared for a different kind of transport,

one for which it was emphatically not designed – a 100-kilometer road trip to Milan. The

preparations took four years, but in mid-August of 2005 a convoy trucked the intact

submarine to Milan, a trip that took four days. Naturally this created something of a

sensation among the local citizenry.

A Submarine in Milan!

Also outdoors on the museum grounds are a few aircraft. This one is a F-84 G

Thunderstreak, a U.S.-built fighter-bomber that was first built in 1954 and which saw

service until 1972. It had a maximum speed in excess of 650 mph, and this one was

used by the Italian Air Force:

F-84 F Thunderstreak (1954)

These airplanes were lined up outside a building called the Aviation and Shipping

Hall, inside of which were several more aircraft, from a variety of eras:

Aviation and Shipping Hall

AgustaWestland AW109 Helicopter (1968)

Aviation Exhibit

Bleriot XI Aeroplane (1909)

Macchi Nieuport Ni 10 Aeroplane (1916)

Ricci 6 Triplane (1919)

Cierva C-30 Gyroplane (1934)

The Aviation and Shipping Hall also has many shipping exhibits, as you've probably

guessed from its name. One of the largest is a sailing ship, a schooner brigantine

called the Ebe. Though it looks like something from the 19th Century or earlier,

it was built in 1921, and was used for transport of passengers and cargo, primarily

between ports along the west coast of Italy and to Sardinia.

The Ebe Afloat

The ship's original name was the San Giorgio, and in 1921 it was the largest

brigantine in the Mediterranean, with the ability to carry 430 tons of cargo. It was

apparently very economical to operate when compared to steamships. During World War

II it was used by the Italian Navy as a minesweeper. After the war, it was briefly

returned to use as a cargo ship, but in 1952 the navy reacquired it and turned it

into a training ship, at which time it received the Ebe name. It was replaced

in 1958 by a newer, sexier training ship, and the Ebe languished from disuse

and eventually found itself being dismantled into many pieces. But instead of being

sold off or disposed of, the pieces were transported to Milan in 1963, where they

were reassembled, to be admired and studied as an exhibit in the Leonardo Museum.

Brig-Schooner Ebe

Ebe from Above

Ebe Cordage

There are also other exhibits from the Age of Sail, including a full-size reconstruction

of part of a gun deck, complete with gunports.

Model of Warship Wasa (1626)

Figureheads

Gun Deck Reconstruction

Cannon, Gun Deck Reconstruction

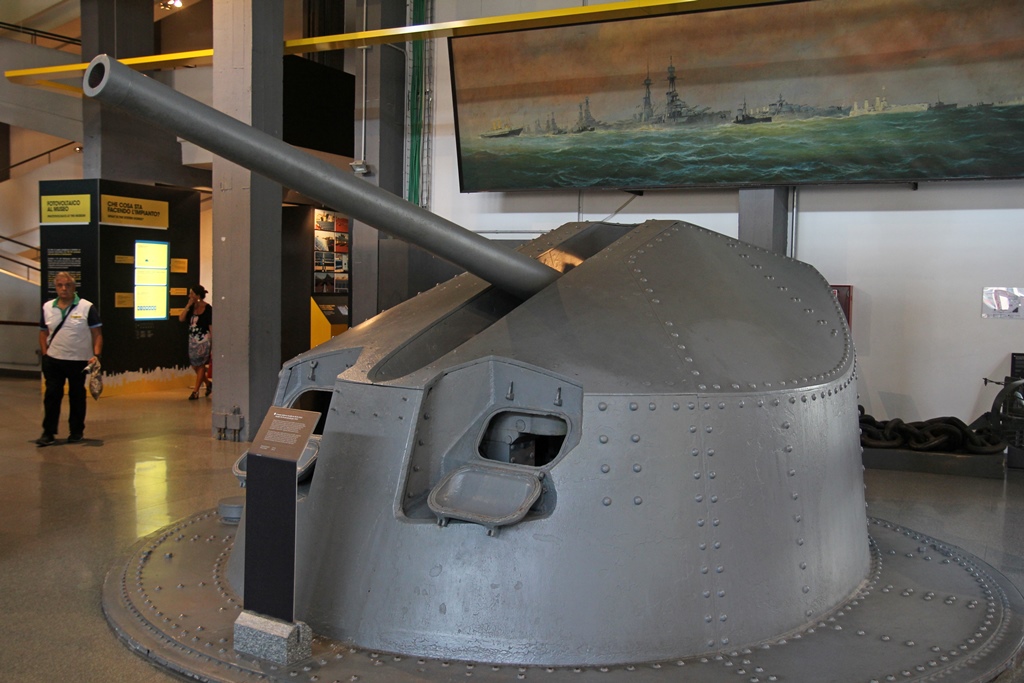

Some exhibits come from the more mechanized navy of the 20th Century.

Anti-Aircraft Gun from Battleship Andrea Doria (1935)

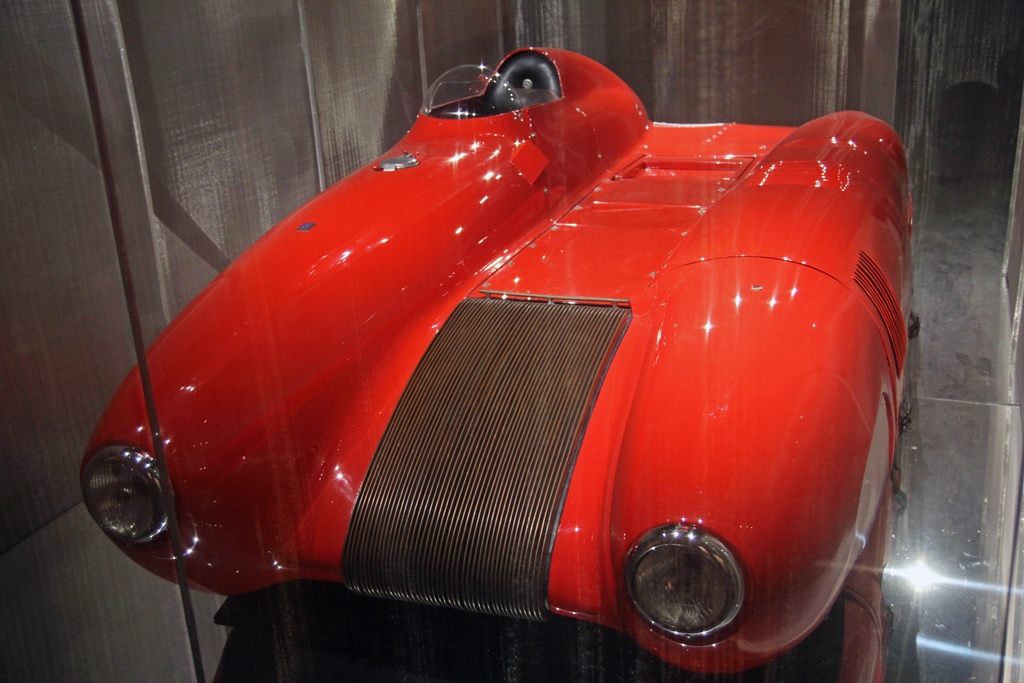

By this time we were about done with the museum and were ready for lunch. On the way out,

we passed through an exhibit of some very interesting-looking automobiles.

Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 (1932)

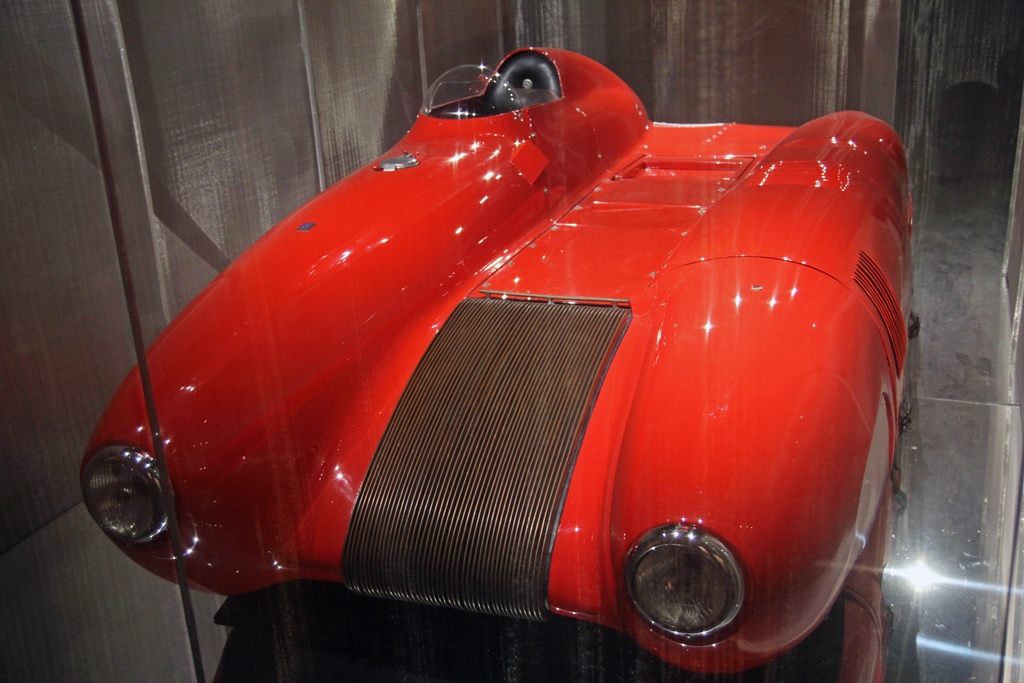

Bisiluro Damolnar (1955)

We found a restaurant and re-fortified ourselves, and we did a little shopping. Then

we proceeded to our next destination for the day, Milan's Brera Gallery.