In Milan there is a district called Brera. The word "brera" comes from a Medieval Italian

term for an expanse of land devoid of trees. This was once an accurate description of the

area, as it was just outside the city wall and was deliberately kept treeless for military

reasons. But now it's a densely-built district of the city which is home to the

Palazzo Brera, a monumental palace which houses several cultural institutions,

including the subject of this page, the

Brera Gallery (or Pinacoteca di Brera).

Palazzo Courtyard

The Brera Gallery is now the principal public gallery for paintings in Milan, but the

palazzo started out as the main building of a Jesuit college in the 17th Century.

In 1773, the Jesuit order was suppressed by Pope Clement XIV, and the palazzo

passed to the Austrian Habsburg dynasty, which ruled northern Italy at the time. In 1776,

Empress Maria Theresa directed that an academy of fine arts be founded at the site, and

the Academy went into business the same year, with Giuseppe Parini as its first dean.

Empress Maria Theresa

Giuseppe Parini

At first the academy didn't have much in the way of actual art to be studied, starting

out with casts of some antiquities that had been provided. But Parini's successors began

to acquire some actual works of art, a process that was greatly accelerated during

Napoleon's occupation of Italy. As the French troops proceeded through the peninsula,

they shut down many monasteries, convents and churches, and sent their works of art to

Milan. Though later years brought the acquisition of other genres of art, the core of

the gallery's collection remains religious in nature. In 1809 the gallery was formally

split off from the academy as a separate institution, though they both remained in the

palazzo.

On entering the gallery, we weren't really aware of its history, but nor were we

particularly surprised at seeing a lot of religious art – pretty much all European art

of a certain era was religious, with an emphasis on Christian themes. But in walking

from room to room, we began to notice something of a lack of subject variety.

Paintings in Room XV

But even though the subjects were well-known and somewhat predictable, it was

interesting to see the different ways in which they were treated by different artists.

Here are some paintings that depict events related to the birth of Jesus and his

early childhood:

The Marriage of the Virgin, Raphael (1504)

Adoration of the Magi, Jan de Beer (1515-20)

Adoration of the Magi, Jan van Dornicke (1520-30)

Adoration of the Magi, Lorenzo Costa il Vecchio (1499)

Madonna and Child, Giovanni Bellini (1510)

Madonna and Child, Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1485)

Virgin and Child with Saints (Camerino Triptych), Carlo Crivelli (1482)

The Virgin and Child with St. Anthony of Padua, Anthony van Dyck (1630-32)

And here are some events from the adulthood of Jesus, leading up to his crucifixion

and beyond:

Supper at Emmaus, Caravaggio (1605-06)

The Last Supper, Veronese (after 1581)

The Last Supper, Peter Paul Rubens (1631-32)

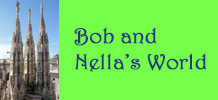

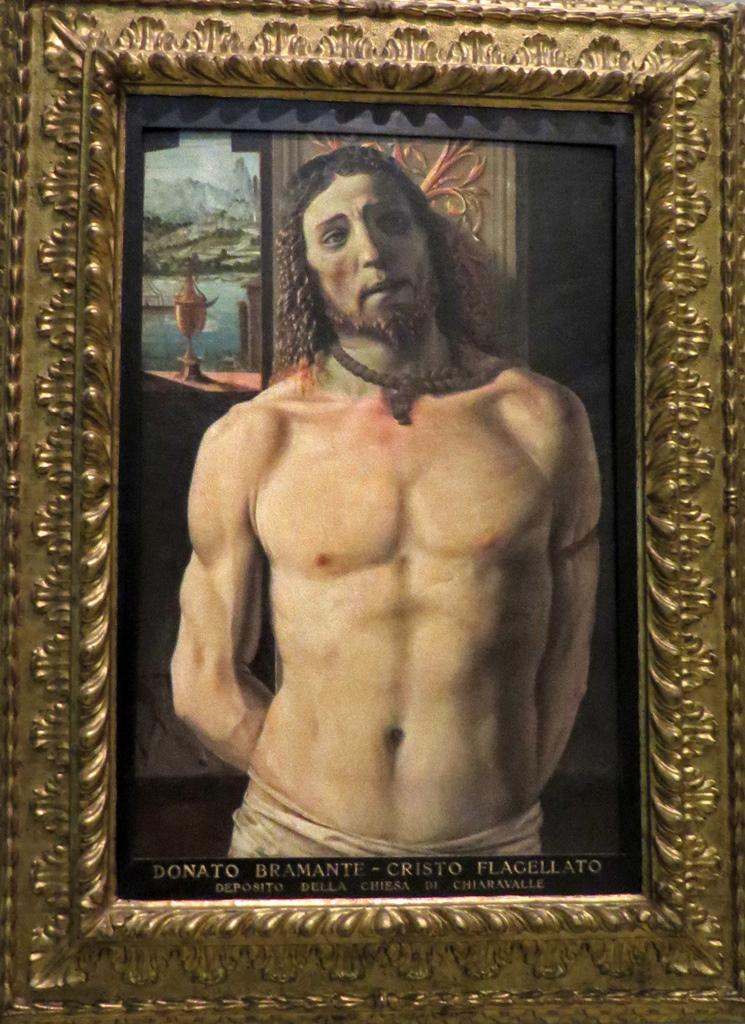

Christ at the Column, Donato Bramante (1490-99)

Crucifixion, Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1729)

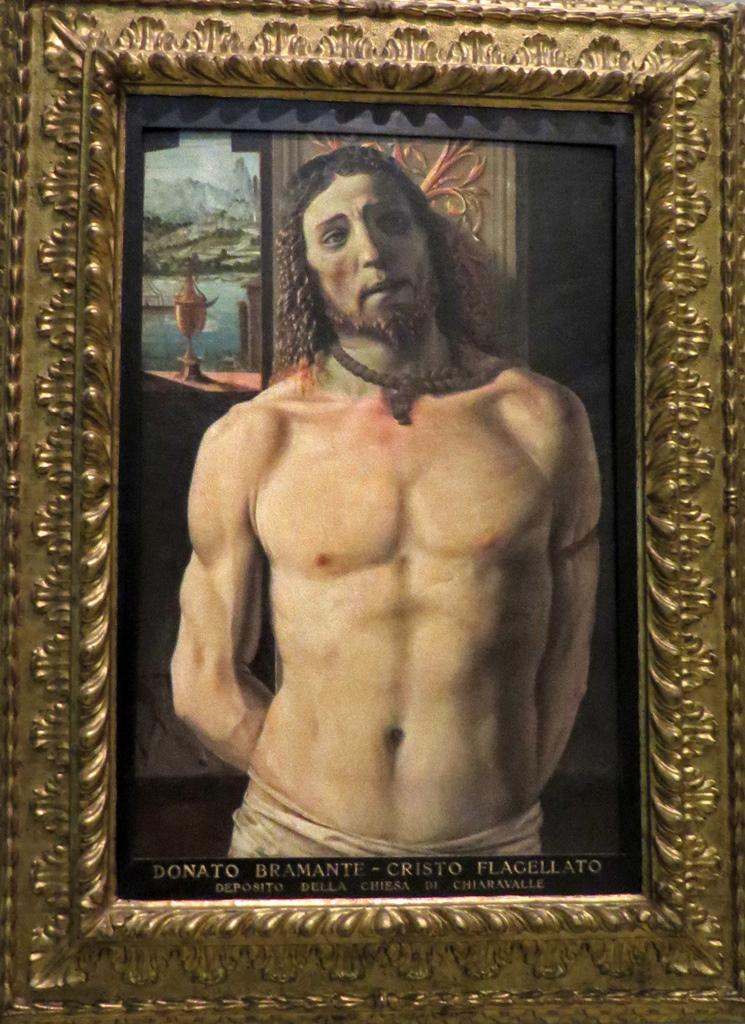

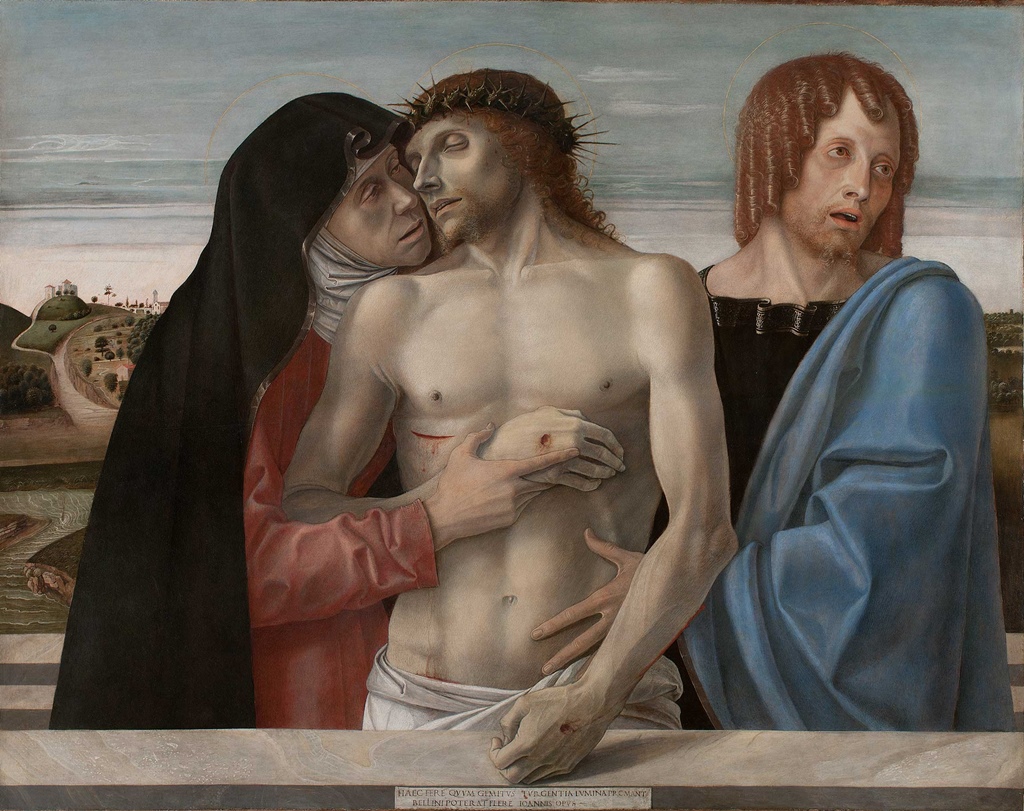

Pietà, Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1460)

Assumption of the Virgin, Carlo Francesco Nuvoloni

Dead Christ, Saints, Coronation of Virgin, Carlo Crivelli (1493)

Coronation of the Virgin, Bartolo and Andrea (ca. 1390 and ca. 1415)

Also commonly depicted in the paintings of the time were the experiences of the

followers of Christ, especially those who later became saints (martyrdoms were

especially popular):

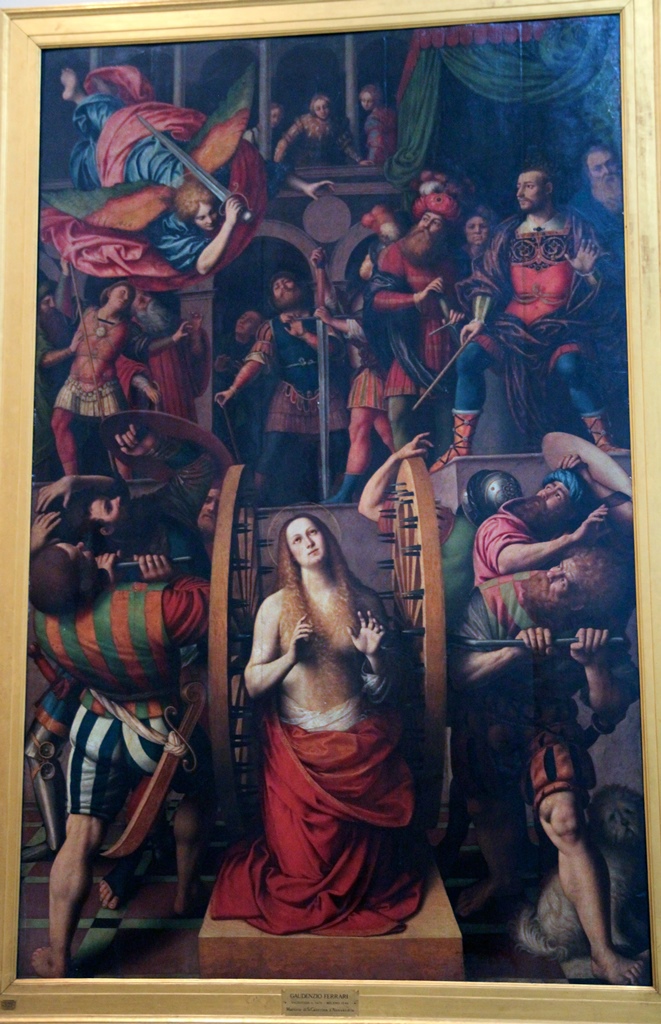

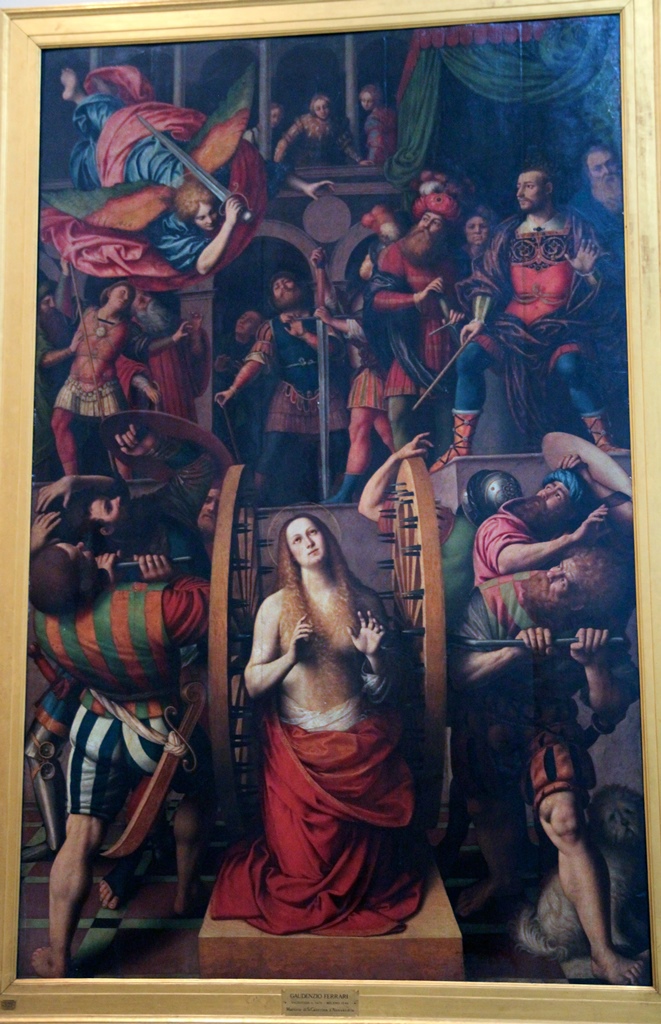

The Martyrdom of St. Catherine, Gaudenzio Ferrari (1540)

St. Francis Meditating on Death, El Greco (1600-10)

St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria, Gentile Bellini and Giovanni Bellini (after 1507)

The Finding of the Body of St. Mark, Tintoretto (1562-66)

A common practice of the time was for a wealthy donor to sponsor the creation of a

painting, under the condition that he (and often his family members) would also be

depicted in the painting, usually kneeling and praying. So often there are paintings

with readily identifiable characters, along with some praying hangers-on whose

identities remain a mystery to this day. In this particular painting, however, the

donors were arguably the most well-known people in Milan at the time – the city's Duke,

Ludovico Sforza (alias il Moro) and his wife, Beatrice d'Este, along with their

children:

Virgin and Child with Doctors and Donors, Maestro della Pala Sforzesca (1494-95)

There is also a certain amount of art preservation going on at the Brera Gallery.

Here are some frescoes that were rescued from Milan's Santa Maria della Pace church:

Frescoes from Santa Maria della Pace, Milan

While most of the religious art was from the New Testament and later, there were

some paintings of events from the Old Testament. Here are a couple:

The Sacrifice of Isaac, Jacob Jordaens (1625-26)

The Finding of Moses, Bonifacio Veronese

Eventually, the subjects permitted in paintings were loosened up some, and

artists started painting events from Greek and Roman mythology:

Nymph Pursued by Pan, Peter Paul Rubens and Brueghel the Younger

Atalanta, Luigi Antonio Acquisti

This eventually opened things up for paintings of subjects that were entirely

secular, either historical or contemporary (now, of course, all would be considered

historical):

The Dying Cleopatra, Guido Cagnacci (1660-62)

View of San Marco from the Punta della Dogana, Canaletto (1740-45)

The Slave Merchant, Vincenzo Vela

Portrait of a Young Woman, Rembrandt van Rijn (1632)

After the gallery was opened, acquisition of new paintings went on. Here are a couple

from the 19th Century:

The Kiss, Francesco Hayez (1859)

Spring Pastures, Giovanni Segantini (1896)

Our visit to the Brera Gallery was the last major tourist attraction we visited in

Milan. But throughout our stay in the city, we'd been visiting less prestigious

points of interest. Continue on to the next page for a look at some of them.