In 1482, a young Leonardo da Vinci made his way from Florence to Milan, bearing

a silver lyre he had created in the shape of a horse's head. He had been sent

to Milan by Lorenzo de' Medici of Florence, and the lyre was to be a diplomatic

gift to Milan's de facto ruler, Ludovico Sforza.

Leonardo da Vinci (not young)

Ludovico Sforza

Ludovico, known as Il Moro, or "The Moor" (for his dark complexion), had

embarked on a number of large public works projects, and talented architects

and artists from throughout Italy were converging on Milan in search of work.

Leonardo was no exception, and to make himself known, he had written a letter

of introduction to Ludovico in which he listed some of the grandiose engineering

projects he felt he could perform for Milan (even though he really didn't have

much experience in this sort of thing), and also mentioned that he could paint.

Ludovico put him to work on several projects, mostly things like floats and

pageants. Leonardo also submitted a design (not used) for a dome for the

cathedral that was being built during this time. And in his spare moments he was

able to complete a painting, the Virgin of the Rocks, which is one of the

few Leonardo paintings that has survived until the present (it's now in the Louvre

in Paris).

Milan Cathedral Under Construction

Virgin of the Rocks

Ludovico also assigned Leonardo the major project of a massive bronze equestrian

statue (to be called the "Gran Cavallo") of his father and founder of the

Sforza dynasty, Francesco I. Leonardo made a careful study of horse anatomy and

came up with a design for a statue whose horse alone would be 23 feet tall.

Drawings from Horse Study

It wasn't clear exactly how such a large statue could be cast, but the first

obvious step was to create a full-size clay model which could be used to make

a mold. Leonardo actually completed this task by 1493, and began planning

out the casting process. Seventy-five tons of bronze were procured for the

statue. The first step of the casting would have been to coat the model with

a layer of wax in which fine details could be sculpted, but other events at

this point caused the project to be placed on indefinite hold. It seems the

French army, under Charles VIII, was marauding around the Italian peninsula

with extreme brutality, using weapons that no one on the peninsula could

match.

Charles VIII of France

Ludovico decided he'd better procure some weapons, so he had the seventy-five

tons of bronze sent to a maker of cannons. The French were successfully

repulsed, but they would eventually return, in 1499, under a new king

(Louis XII), and would successfully take over the city.

Louis XII of France

Leonardo and the other artists in residence would take flight to other

cities (Leonardo would end up in Venice), and the French soldiers would use

the gigantic clay model for target practice, bringing an end to one of the

many projects Leonardo would never complete.

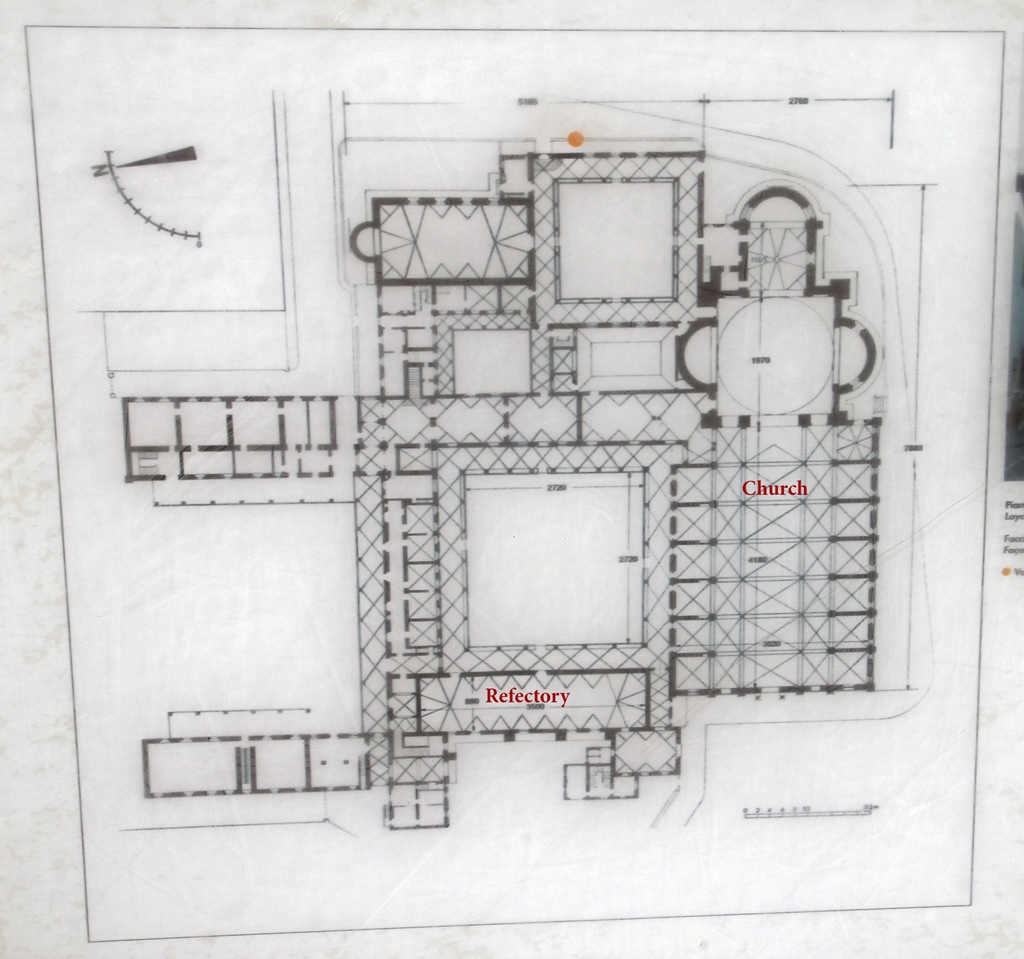

In 1495, before the Cavallo's ignominious end but after Ludovico

repurposed all that bronze, he came up with a new project for Leonardo.

There was a new Dominican convent in Milan, which Francesco had ordered

built, which had been completed in 1482. It was called Santa Maria delle

Grazie ("Holy Mother of Grace"), and Ludovico had decided around 1492

that this would be a suitable location for a mausoleum - a resting-place for

the House of Sforza. Architects from around Italy were recruited to make

proposals for the upgrades that would be necessary, but the job went to an

architect who was already working for Ludovico, Donato Bramante (a good

choice – within about ten years, Bramante would be chief architect of the

new St. Peter's Basilica in Rome).

Donato Bramante

The plans included knocking down the eastern end of the church and adding a

towering extension that would include a dome. Leonardo had ideas for the

extension and was interested in working on it. He was even a good friend

of Bramante's, but this was not enough to get him involved in working on

the church. Ludovico had a different idea.

Heraclitus and Democritus (Leonardo/Bramante?)

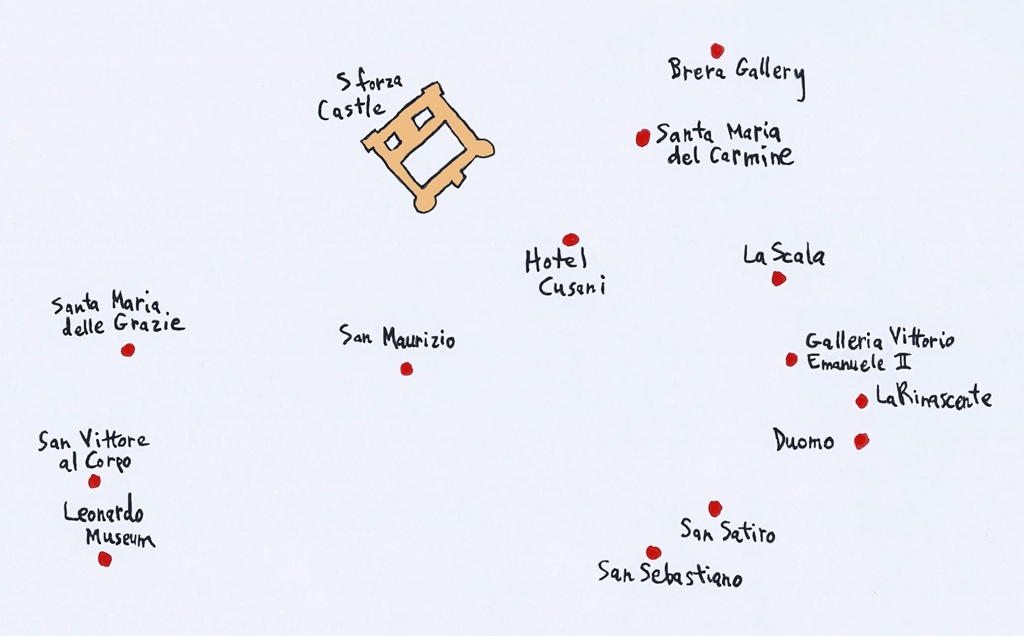

Santa Maria delle Grazie was not just a church – it was a convent, populated

by Dominican friars who lived, studied, prayed and took their meals there.

Meals were communal affairs, served in a large room called the refectory (or

cenacolo in Italian). The meals consisted of what has been called

"humble fare" – humble to the point of malnutrition – and were largely silent,

despite the Dominican penchant for vociferous preaching when outside the

convent walls. In the refectory, speaking out of turn could lead to missing

your next lump of cheese. The room was dimly lit – the only daylight came

from a row of small windows near the ceiling of the western wall. But there

wasn't much to look at anyway – as with many indifferently funded religious

facilities, decoration was minimal. But Ludovico Sforza aimed to change the

decoration problem, at least. Refectories at the time that were decorated

tended to have frescoes somehow related to food. A couple of scenes often

depicted were Abraham preparing food for the angels (from Genesis) and the

Christian miracle of the loaves and fishes. But the most popular scene by

far was that of The Last Supper.

Last Supper (Spanish, ca. 1495-1500)

Leonardo would be tasked with producing a Last Supper for one of the walls of the

refectory. But as you're undoubtedly aware, this would not just be a Last

Supper. Even five hundred years later, this would be The Last Supper.

Seeing The Last Supper can take some planning. The painting is one of the most

famous in the world. It's also very fragile, and measures taken for its protection

include a limit of 900 visitors a day. For this reason, reservations normally need

to be made months in advance

(www.cenacolovinciano.net), or you may get

lucky if someone doesn't show up for their timeslot. There is also a third option.

There are a number of tours of Milan you can join that include a visit to The Last

Supper. This is considerably more expensive than making your own Last Supper

reservation, but can be much easier. Also, tours normally include a guide and a

look at some other interesting attractions in the city. We joined a walking tour

of the general area of Santa Maria delle Grazie, and were able to get a

reservation less than a month before our visit. We went through

www.milan-museum.com, but there are undoubtedly

other tour providers.

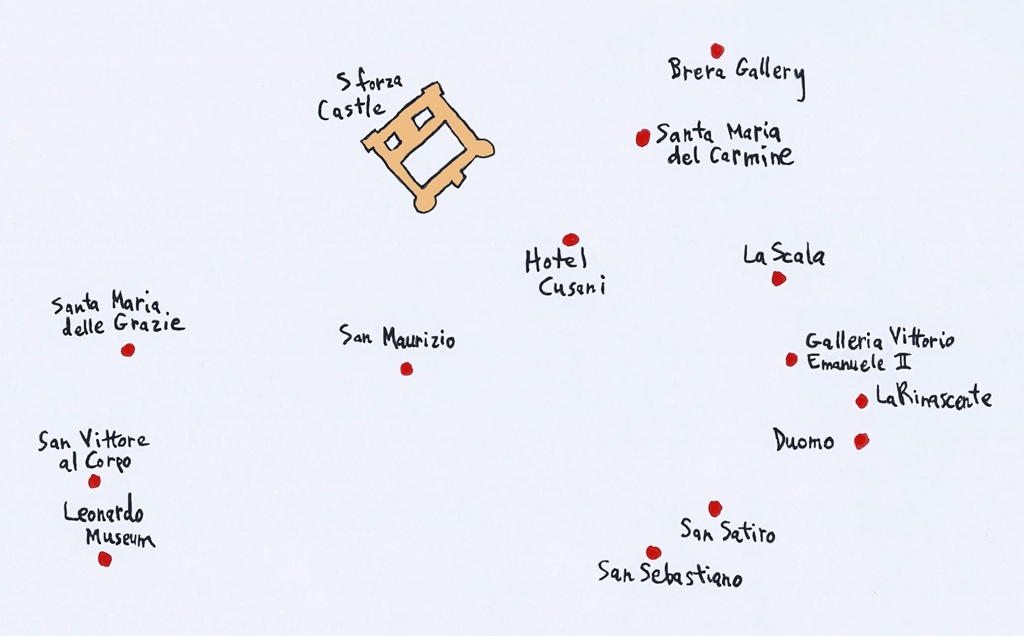

Milan Old Town

There are a couple of Metro stops near the convent, but our hotel was about half

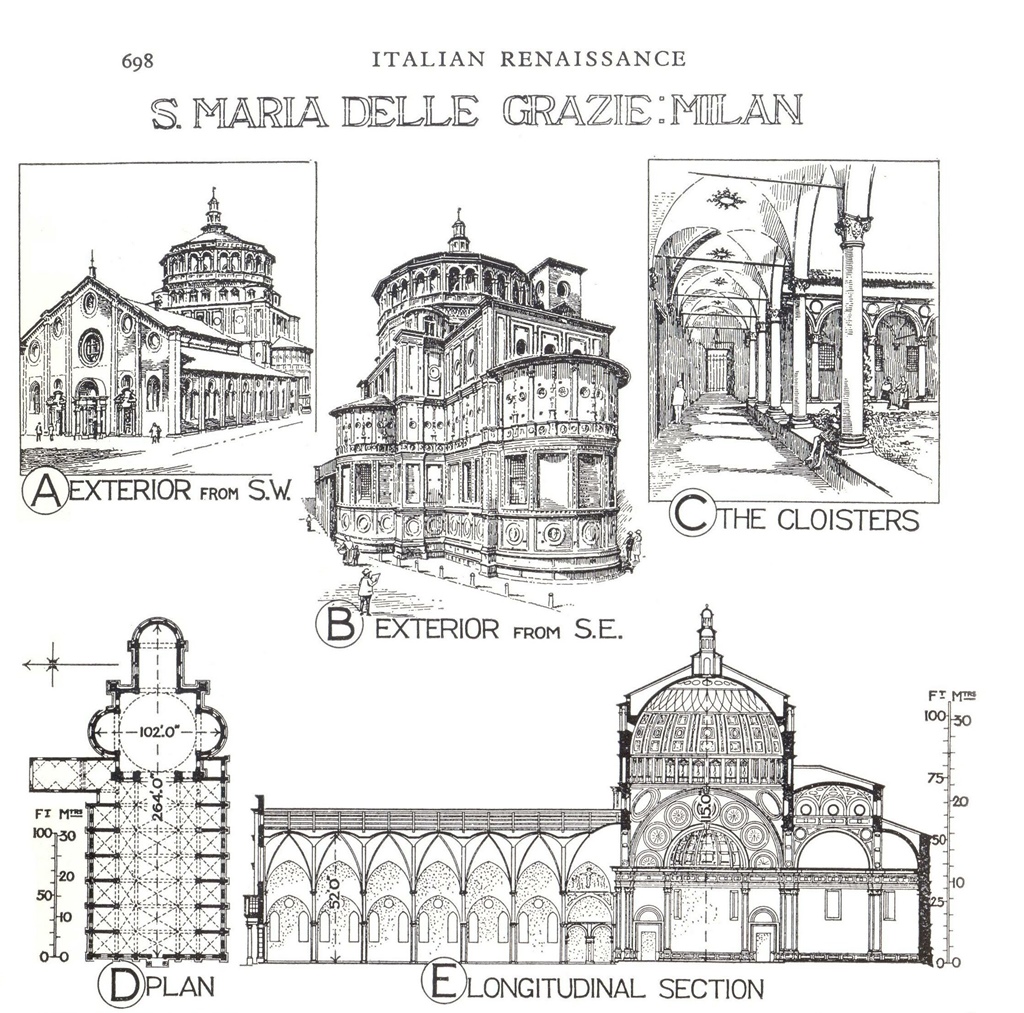

a mile away, so we just walked. From the outside, the red-brick church clearly

dominates the convent, with Bramante's eastern extension obviously a lot more

ambitious than the rest of the church.

Church, Santa Maria delle Grazie

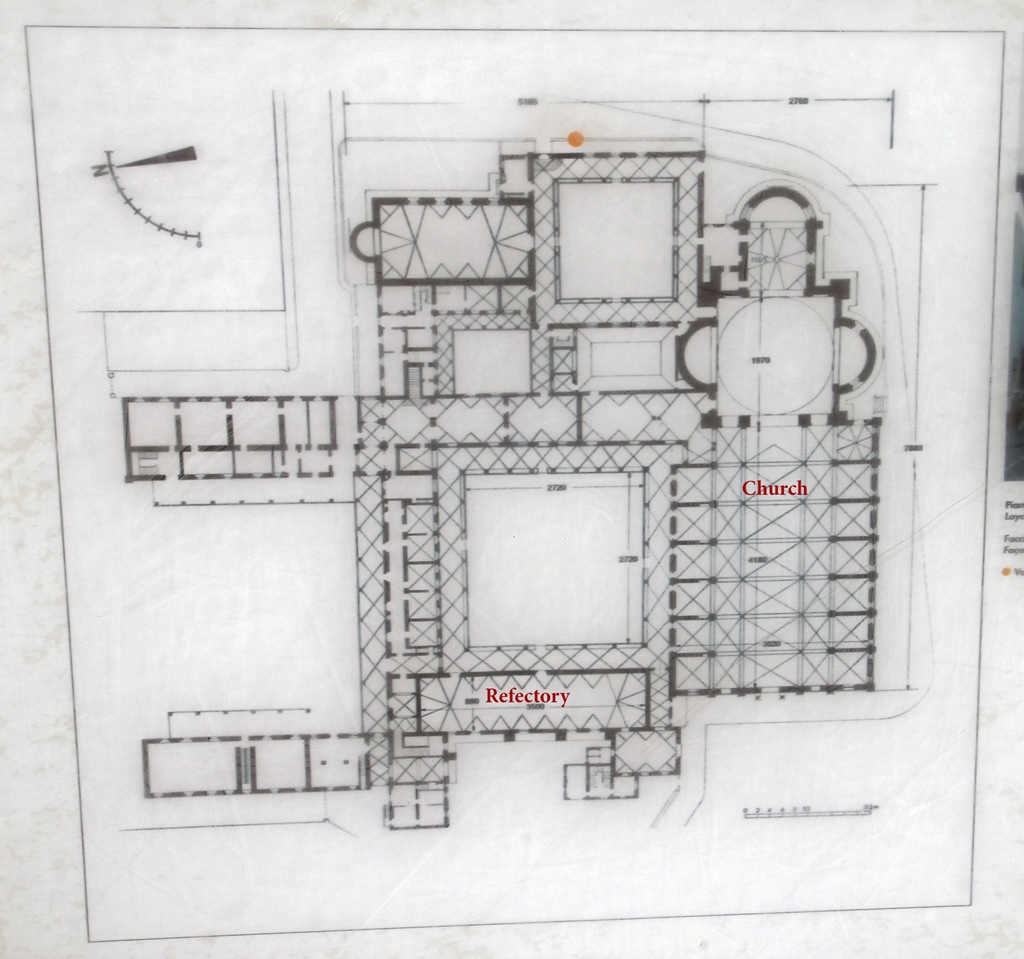

Convent Layout

Church Layout

Church with Dome

Eastern Extension

Arch Above Doorway

We arrived early, so we had some time to look around inside the church

before we had to meet up with our tour group. We found the church to be

attractive, though inconsistent in style. The older part of the church,

though only pre-dating Bramante's extension by a few decades, was clearly

Gothic, while the extension, which included the apse and the area under

the dome, was Renaissance. Structurally, there were no surprises in the

Gothic section, though there was more attention paid to decoration than

in most Gothic churches we'd visited. We spent some time looking around

at the nave and side chapels.

Church Interior

Vault, Cappella Marliani

Vault Fresco

Archway

Column Decoration

Virgin and Child Figure

Saint and Child Figure

The apse area, which holds the main altar and several choir stalls, has

a much newer look and is considerably brighter.

Main Altar

Figure, Main Altar

Figure, Main Altar

Choir Stalls

Counter Space, Main Altar

Somewhere in the extension area is the tomb of Ludovico Sforza and his

wife Beatrice d'Este. Beatrice died in childbirth in 1497 at the age of

21, attempting to give birth to her and Ludovico's third child (which was

stillborn). Ludovico eventually ended up as a prisoner of the French and

died in captivity in France in 1508 (aged 55). His body eventually found

its way back to Santa Maria delle Grazie for burial next to Beatrice.

This tomb ended up being the full extent of the Sforza mausoleum idea.

Ludovico and Beatrice's two surviving children lived to be the last two

Dukes of Milan from the House of Sforza (which ended in 1535), and were

eventually buried elsewhere. We were a little rushed due to the need to

keep our tour appointment, so we never saw the tomb, but here's a picture

from the Internet:

Tomb of Ludovico and Beatrice

We exited the church and found a group of people accumulating in front of it,

one of whom was wearing a striped shirt - on being accosted, he admitted to

being our tour guide. We presented our tour voucher, and eventually we were

all ushered into the convent entrance.

Entrance to Convent

The first destination of the tour was The Last Supper. Getting to The Last

Supper is a little complicated. The painting is very fragile and moisture is

its enemy, so we had to pass through successive chambers of diminishing

humidity (all the while listening to an informative narration from our guide),

before entering the Refectory.

The Refectory is a long, narrow room, 116 by 29 feet. In the days when meals

were served here, there would have been tables lined up around the room's

perimeter, but these days all furniture has been banished, except for a few

benches at one end, set up for visitors to sit on while contemplating The Last

Supper. Photography was forbidden, so we only got one picture by accident.

Here's the picture, along with a much better one off the Internet, which can

be downloaded from any number of places (including here):

Inside the Refectory

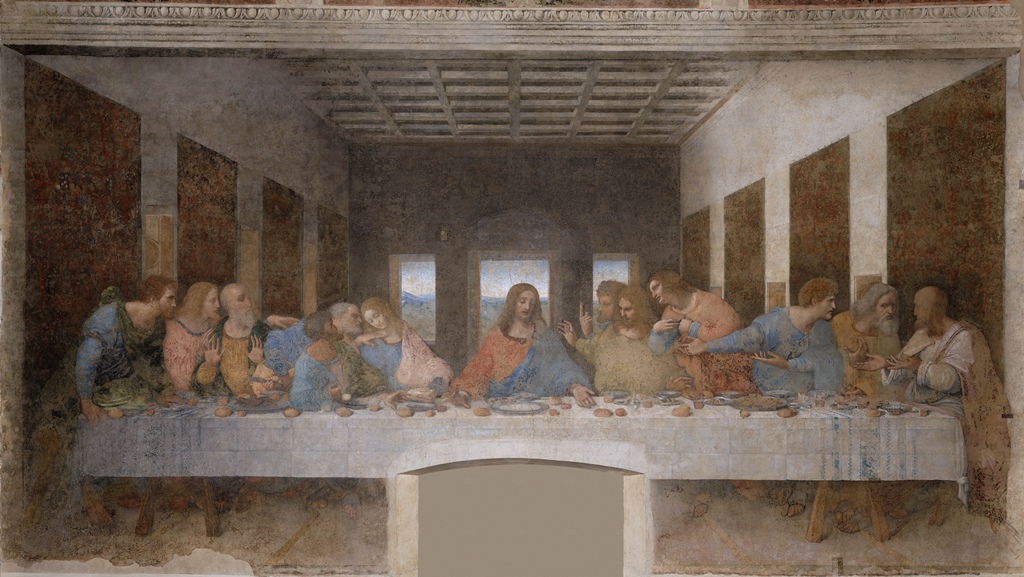

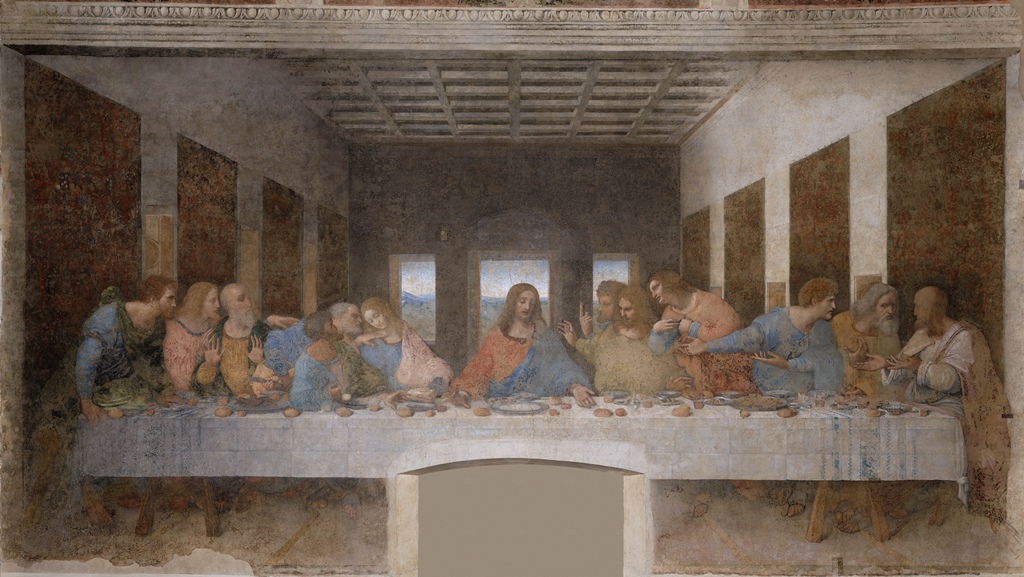

The Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci (1495-98)

The instantly-recognizable Last Supper was clearly a major project. It

measures 29 feet by 15 feet and is filled with detail. It captures the moment

during the Last Supper when Jesus tells his apostles that "one of you shall betray

me". The reactions are varied, ranging from disbelief, to argument, to speculation

(except for Judas, who doesn't need to speculate). The figures in the painting,

from left to right, are: Bartholomew, James the Lesser, Andrew, Judas, Peter, John,

Jesus, Thomas, James the Greater, Philip, Matthew, Thaddeus and Simon. Leonardo

clearly took pains to get the perspective of the painting correct – there is

actually a small hole in the wall at the painting's "vanishing point", where there

was no doubt once a nail from which one could stretch a string to get the angles

right. The vanishing point, of course, is at the head of Jesus.

The Last Supper is probably one of the most analyzed and argued-about

paintings ever. People have made varying assertions as to who the figures really

are, what they're doing or saying, whether the painting represents a moment or a

sequence of moments, what's going on with the objects on the table, and what every

figure or detail of the painting symbolizes. Those of you who've read The da

Vinci Code are probably familiar with some of the theories voiced by Dan

Brown's characters, including the idea that the John figure is really Mary

Magdalene, who is married to Jesus (an idea not generally accepted by reputable

theologians). Personally, I suspect Leonardo is watching all this from somewhere

and having a good laugh at everyone's expense. But the fact that the painting is

even there to be argued over is something of a miracle.

In the 15th Century, if you wanted to paint a wall with a picture that would last

a long time, you would paint it using the fresco technique. A fresco is painted

using water-based pigments, applied to freshly-spread plaster that is still wet.

When done correctly, the pigment soaks into the plaster, and when the plaster

dries, the painting is essentially part of the wall. The technique is very

difficult for a number of reasons. The plaster and the paint both have to be

formulated right, usually by assistants to the painter. The plaster needs to

contain lime, which is extremely corrosive, to brushes, clothing and skin. And

the plaster doesn't stay wet very long – maybe a few hours. For this reason,

only a small part of the picture can be worked on in a given session. A

plasterer would spread a small section of plaster, and the artist would have to

begin painting immediately, and not waste any time. And do it right – mistakes

could only be rectified by chiseling out the offending section and doing it over

again. To save time and minimize mistakes, a painter would usually come prepared

with a plan, in the form of a paper drawing (called a "cartoon") of the section

to be painted. The outlines of the images to be painted would be transferred to

the plaster, usually by blowing charcoal dust through pinholes in the cartoon.

And then the painter would paint like a demon, for as long as it took, or as long

as the plaster allowed.

Very few painters of the era (or any era, for that matter) were able or willing

to paint frescoes, and Leonardo da Vinci was not one of them. He had no

experience in the technique, and it was incompatible with his style of painting.

He achieved some of his effects, such as color gradation and emphasis, through

layering techniques, which couldn't really be done in fresco. Also, he could be

very deliberate and often painted over things when he needed to correct them.

Additionally, two of the colors he intended to use, ultramarine and vermilion,

produced unacceptable chemical reactions with the lime in the plaster. So

Leonardo painted The Last Supper using a technique called a secco, which

was basically painting on dry plaster. For paint he used tempera, which

consisted of dry pigments combined with an organic binding agent (eggs were

commonly used for this purpose).

Leonardo completed the painting in 1498, to rave reviews, and the friars of

Santa Maria delle Grazie had a gorgeous, vivid, mint condition da Vinci to gaze

at while they downed their humble fare. For awhile. But within twenty years,

people started to notice that some of the paint was flaking off, visibly

degrading the painting. It turned out that humidity from the adjacent kitchen

was taking a toll, and soot from the many candles used over the years had dimmed

the colors. The deterioration continued over the years, and by the end of the

16th Century, one visitor pronounced it "a total ruin". In 1652, the convent

friars decided they needed a door more than they needed the section of the

painting with Christ's feet, so they cut a hole in the wall, with the vibrations

from their pickaxes causing further damage. Several restoration attempts were

made which included ugly overpainting and coating the wall with various

"protective" substances that turned out to be anything but. Napoleon arrived in

1796, and one of his generals used the Refectory as a stable. In 1800, there

was a flood which covered the Refectory floor with standing water, and the

painting grew green mold. In 1943, Allied bombing collapsed the east wall of

the Refectory. The painting had been protected with plywood and sandbags, but

the vibrations from the explosion didn't exactly help, and the painting was

exposed to the elements until the Refectory roof could be put back.

WWII Bomb Damage

But in the 1970s it was finally decided that something drastic needed to be

done to restore and protect whatever was left to protect of the painting, so

the Refectory was sealed off in 1978 and a team got to work, armed with the

latest technology. The overpaintings and protective coatings were carefully

removed, and some of the missing areas were filled in with watercolors (to

indicate they weren't original). The painting was finally put back on

display in 1999, with the precautionary visitation measures described above.

People were (and are) obviously happy to see it again, but some art

historians have been less than enthralled with the result.

For a look at how the painting might look if it had been done as a true

fresco, there is a crucifixion fresco at the opposite end of the Refectory

that was done in 1497, by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano. There are some

areas of missing plaster, but overall the fresco is in pretty good shape.

It also miraculously survived the 1943 bombing - it's visible in the

picture above, at the far right. But near the bottom corners of the fresco

there are two figures that look like they've pretty much disappeared.

These are small portraits of Ludovico and Beatrice which had been added by

Leonardo a secco, after the rest of the fresco had been completed:

Crucifixion Fresco, Giovanni Donato da Montorfano (1497)

For another "what-if" look, there is a full-scale copy of the painting

that was painted in oil by Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli (AKA Giampietrino), who

had worked on the original as an assistant. This was painted around 1520,

and is in the collection of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. It was

used as a reference for the 1978-99 restoration, and shows many details

which have faded from the original.

Copy of Last Supper, Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli (ca. 1520)

After spending our allotted 15 minutes with the painting, we were herded

out of the Refectory and the convent, and embarked with our group on our

walking tour of the neighborhood. Continue to the next page to see what

happened next.