The Duomo

It would take some doing to not notice Milan's cathedral, known as the Duomo. It's in

the middle of town, it's covered in white marble, and some might say that it's a tad

over-decorated. It's also the third-biggest church in Europe (after

St. Peter's Basilica in

Vatican City and the Cathedral

of Seville) and the

fourth-largest in the world. It's 520 feet long, 305 feet wide at its widest, and 356 feet tall.

It's located in the Piazza del Duomo, a square of a size (183,000 square feet) worthy of its most

prominent building. The Duomo is the most-statued building in the world, with 3,400 statues

decorating its interior and exterior. There are 135 spires (each with a statue of a saint on top)

and 150 gargoyles. Historical impressions of the Duomo have been largely admiring – Wordsworth and

Tennyson wrote poetry about it, and Mark Twain devoted an entire chapter to it, in his book The

Innocents Abroad. But the praise hasn't quite been unanimous – Irish author and professional wit

Oscar Wilde famously detested it, calling it "an awful failure" in an 1875 letter to his mother.

Construction of the cathedral began in 1386, when Milan was under the rule of Gian Galeazzo Visconti,

who also happened to be the cousin of the archbishop.

Gian Galeazzo Visconti

The new cathedral would replace two churches in the area, named for Santa Tecla (built

around 355 A.D.) and Santa Maria Maggiore (from 836), which were in poor condition. Building

the new cathedral in the traditional Lombard Romanesque style, using brick, was considered,

but instead it was decided to build in a new style known as International Gothic, and to use

marble. An organization (the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo, still in existence) was

created to manage the creation of the cathedral (today they manage upkeep and restoration),

and Gian Galeazzo granted the organization exclusive use of the Candoglia marble quarry (on

the shore of Lake Maggiore, and still in use for procurement of restoration materials). The

architecture presented more of a problem, as International Gothic was virtually unknown in

Italy, having been introduced mainly in France and Germany. So architects had to be

recruited from north of the Alps, and recruitment of architects from throughout Europe became

an ongoing process.

Construction proceeded from the east end of the new cathedral, with the apse, the sacristies

and eventually the transept being done first. The Santa Tecla church was demolished in the

early going, but parts of the Santa Maria Maggiore church remained in use as the nave of the

new cathedral gradually lengthened westward. In fact the Santa Maria Maggiore façade

remained in use as the façade of the new cathedral for centuries, and was even disassembled

and reassembled farther west a couple of times, as the new nave was being extended. They

stopped doing this after a while, as the old façade was looking much the worse for wear.

The construction continued in fits and starts, as the builders would periodically run out of

money or ideas, and the beginning of an idea for a façade remained in place for many years.

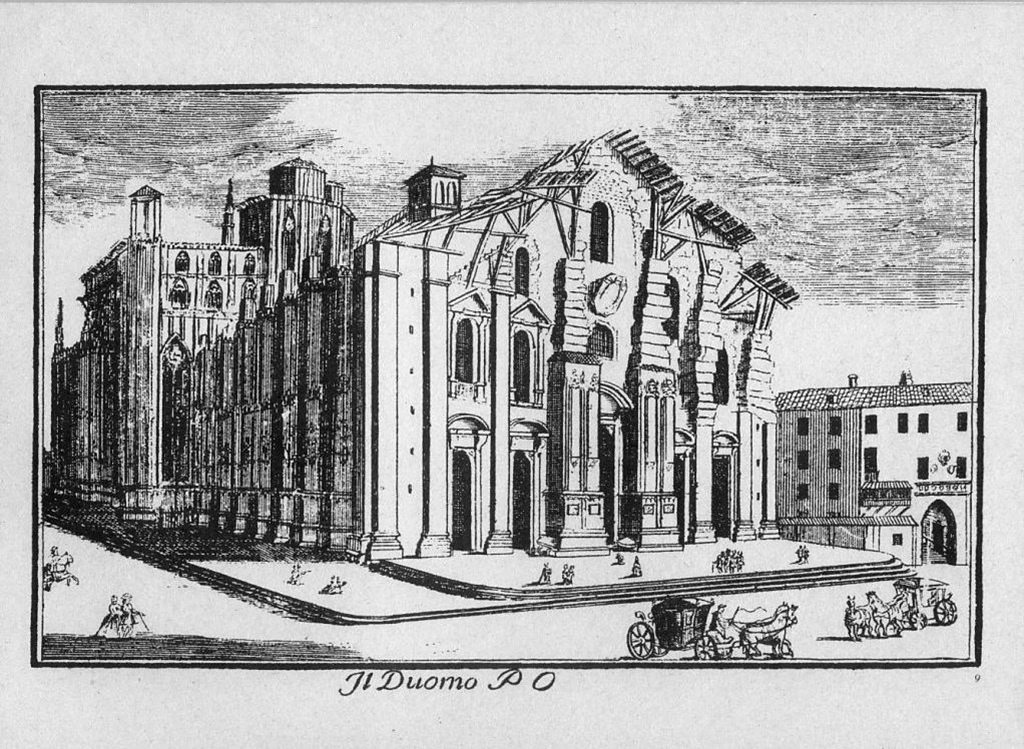

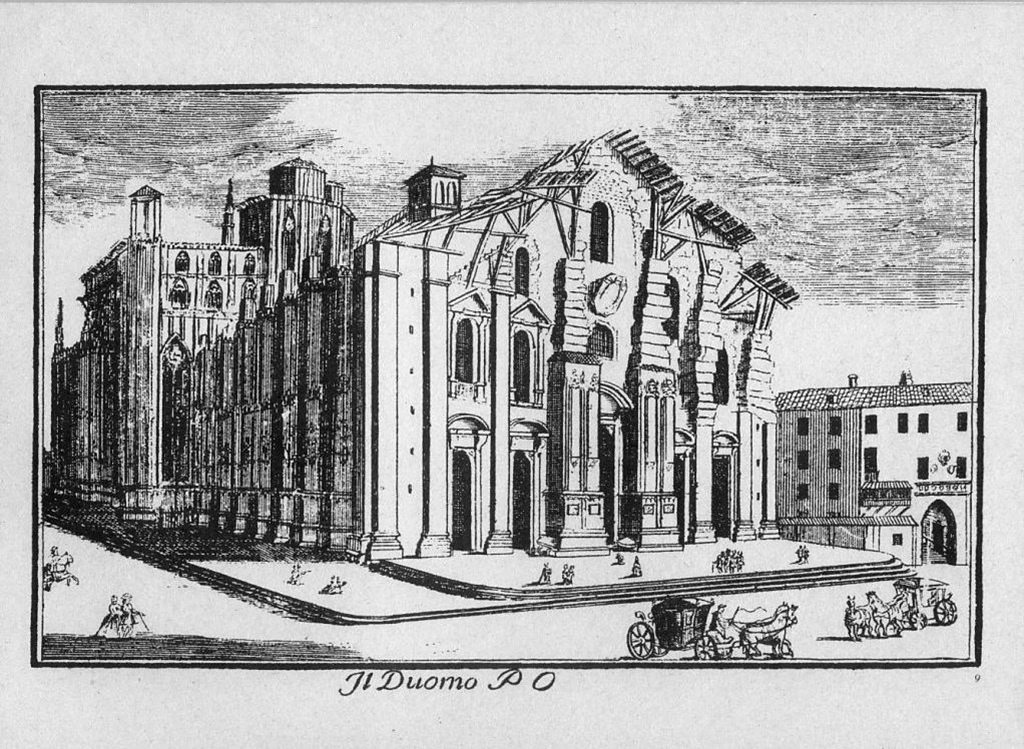

The Duomo, circa 1745

In 1805, Napoleon Bonaparte came to town to have himself crowned King of Italy (which

happened in the new cathedral). While in Milan, he ordered the cathedral's completion,

promising to reimburse the expense from the French treasury. The reimbursement part of

the project never happened as it turned out, but the order served to jumpstart the

project, which had been in limbo for an extended period. The new façade was finished

in 1813, and work continued on the spires (one of which has a statue of Napoleon on top

of it) and statuary, as well as the enlargement of the Piazza del Duomo.

Napoleon on his Imperial Throne, Ingres (1806)

In the 20th Century, work was done on the cathedral doors, with a pause for repairs of

damage inflicted during World War II. The last doors were finally installed in 1965.

We approached the Duomo from the north (it was shady there) before working our way around to

the façade, finding something to admire every inch of the way.

North Wall and Windows

Statues on Wall

Statues Holding Up Corner of Church

Above Front Door (Door #2)

Stone Produce

Statues Between Doors 3 and 4

The Duomo has five front doors which correspond to the five naves inside the church. They

are all made of bronze, and all were installed in the 20th Century. The most elaborate and

oldest is the one in the center, created by local artist Ludovico Pogliaghi between 1894

and 1908.

Center Door

Center Door (detail)

Entry into the cathedral is not accomplished through the center door, but rather through the

second door from the left. On entering the church, there are many things to take in, but

the first thing you notice might be the high ceiling (at 148 feet, the Duomo has the highest

Gothic vaulting of any completed church) and the forest of massive columns (there are 40,

each 80 feet in height, with larger-than-lifesize statues encircling it near the top) that

hold it up.

Columns

Columns

The upper parts of the walls are punctured by several stained-glass windows. These windows

are of varying ages, dating from the 15th Century all the way into the 20th Century. They

depict stories from the bible, as is customary:

Stained Glass

The lower parts of the walls are largely devoted to side altars and monuments, also customary:

St. Ambrose Altar, Pellegrino Tibaldi

Monument to Martin V, Jacopino di Tradate (1424)

Monument to Medeghino

Moving up toward the front of the church, the presbytery area comes into view:

Presbytery Area

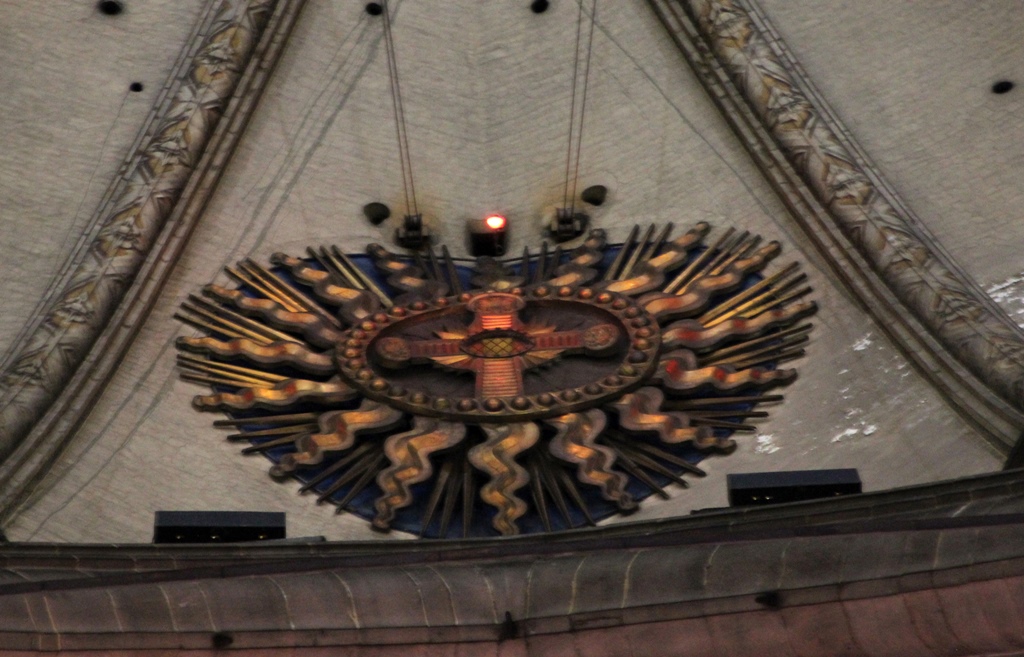

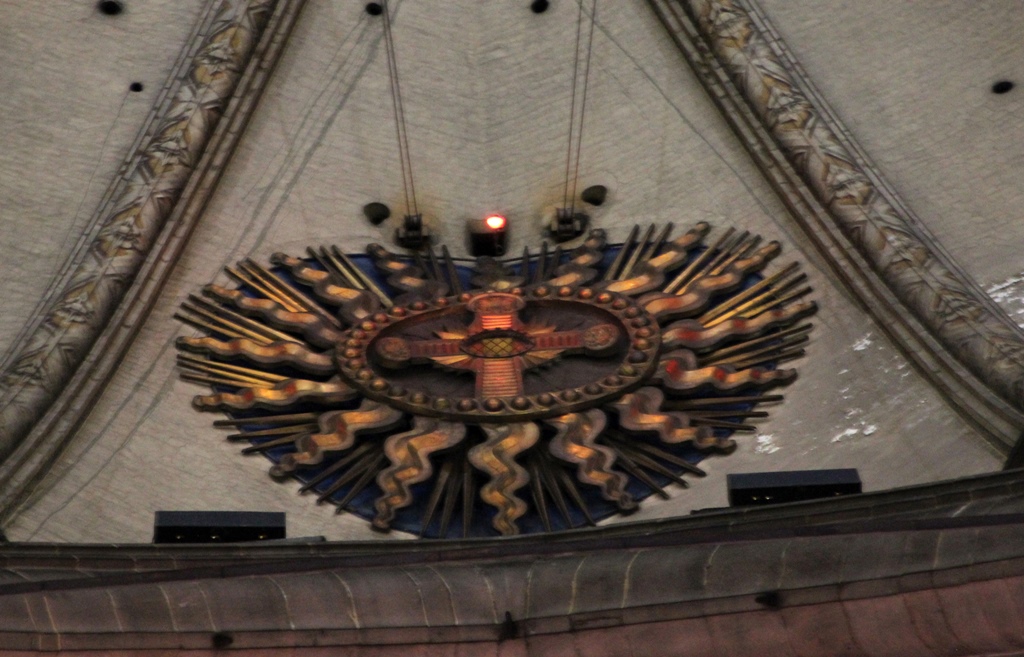

There are a couple of interesting items suspended high above the presbytery. First, in

the picture above you can see a small red light in the ceiling, above the stained glass but

below the crucifix (you might have to select the picture to bring up a larger version).

This light marks the location of a tabernacle that holds the church's holiest relic, the

Santo Chiodo, or Holy Nail, which is thought to have been used in the Crucifixion of

Jesus. Once a year, around September 14, there is a ceremony called the

Rite of the Nivola, in which the

archbishop is raised in a sort of a large basket (the Nivola, suspended by cables)

to the tabernacle, where he extracts the Nail and brings it down, to be put on display for

three days. At the end of the three days, he gets back in the basket and takes the nail

back up to the tabernacle, where he locks it away until the next year. The basket dates

back to at least the 16th Century, at which time the lowering and raising was done by men

on the roof (this is now done by machinery).

Tabernacle of the Holy Nail

The Nivola

Also up the vaulting above the presbytery is a crucifix:

Crucifix and Arch

Crucifix, Columns and Vaulting

The presbytery itself is quite large, so as not to appear lost in this behemoth of a church.

The presbytery's design dates from 1575, with its wooden choir stalls having been installed

in 1614. The presbytery is the site of statues and several paintings, and at its center is

a bronze temple-like structure called the ciborium, which was designed and built by

Pellegrino Tibaldi in the 1580s. The side walls of the presbytery are dominated by organ

pipes. The organ was built in 1938 and is the largest in Italy. At the front of the side

walls are two pulpits which wrap around the bases of two of the aforementioned support

columns.

Presbytery Area and Choir

Ciborium and Presbytery Area

Window of the Apocalypse

Columns and Right Pulpit

Organs and Pulpits

Right Pulpit

In the north transept, there is a large 17th Century altar devoted to the Virgin of the

Tree. Also in that part of the church is a large candle-holder known as the Trivulzio

Candelabrum. This is considered to be one of the cathedral's great artworks, but

unfortunately we weren't able to get very close to it. The base and the stem of the

candelabrum were done at different times (the 12th and 16th Centuries, respectively),

obviously by different artists.

Altar of the Virgin of the Tree (17th C.)

Trivulzio Candelabrum (12th C.)

Window Above Altar of the Virgin of the Tree

Saint Bartholomew was one of the original apostles. Following the Ascension, Bartholomew

and fellow apostle Judas Thaddeus are said to have headed for India in order to convert people to

Christianity. From India, the two apostles are said to have gone to Armenia for the same

purpose (both are considered patron saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church). Somewhere

around this time, Bartholomew is thought to have been martyred by someone who disapproved

of his activities. There is some disagreement over exactly where and how this happened.

Some think he was actually martyred in India, while others feel he met his end in Armenia.

As far as method, there are accounts that he was crucified upside-down, like his fellow

apostle Saint Peter. But other accounts point to a more gruesome procedure in which he

was skinned alive and then beheaded. Most artistic renderings of the martyrdom depict the

latter method – it's certainly more dramatic. There is a 1562 statue of St. Bartholomew

in the Duomo in which Bartholomew has been skinned but not yet beheaded. The statue, by

Marco d'Agrate, depicts a Bartholomew who doesn't look particularly concerned, wearing his skin

draped around his neck. The anatomical detail is impressive. This is said to be the most

popular statue in the church. People are creepy.

Statue of St. Bartholomew, Marco d'Agrate (1562)

We passed the St. Bartholomew statue on the way to the area between the presbytery/choir

and the wall of the apse. Walking in this area, called the ambulatory, gives a visitor a

nice close-up view of the decorated back wall (called the retrochoir) that encloses

the choir and of the three gigantic stained-glass windows of the apse (each 68 feet tall and 28

feet wide).

Reliefs in Retrochoir (17th C.)

Stained Glass Window, Bertini Family (19th C.)

Window of the Apocalypse (detail)

Underneath the presbytery and choir there is a circular 16th Century chapel, known as the

crypt. Unlike many crypts, this one isn't filled with tombs of saints and bishops, but

is mainly just a chapel. There is a small box in the center of the room, underneath the

altar, that contains relics of saints and martyrs, but the room is mostly filled with

choir stalls, seats and decorative elements. Also underground and across from the crypt

is a small room, called the Scurolo, which contains a crystal and silver casket,

designed in 1606, with the mortal remains of San Carlo Borromeo (1538-84), a leader of

the Counter-Reformation and former Archbishop of Milan. Among his many accomplishments

was the establishment of seminaries for the education of candidates for holy orders.

Above Entrance to Crypt

The Crypt (16th C.)

The Scurolo (17th C.)

Like some cathedrals, the Duomo allows visitors to ascend to some scenic viewpoints

in the church's structure. For some churches this means bell towers, but in Milan you

can actually walk around on the roof. And in addition to the scenery, you are

surrounded by statuary, spires and flying buttresses. An elevator is available to

take you most of the way up (for a fee), but you can take the stairs instead if you'd

rather (for a smaller fee). Nella wasn't interested in either stairs or elevator, but

to me this sounded like one of the coolest things you could do in Milan. And it was.

On top of the cathedral there are several interconnected "terraces" which can be

explored, but only two appeared to be available at the time of our visit. One was on

the north side of the church, somewhat lower than the roof over the central nave.

Spires and Flying Buttresses

View from North Terrace (0:20)

Duomo and Piazza del Duomo

Spires and Flying Buttress

North Terrace

Intersecting Buttresses

Group of Spires

The other terrace was a big one over the central nave. A lot of other tourists also

thought this would be an interesting place to visit. The tallest part of the church

is the Great Spire. It was surrounded by scaffolding during our visit, but we could

see the top of the spire, a 13-foot-tall gilded statue called the Madonnina (1774).

Main Terrace

Lantern and Scaffolding

Spires and Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

Main Terrace with Tourists

I returned to ground level and found Nella. By this time it was late afternoon, and we'd

had enough activity for one day. We found dinner and returned to our hotel. As usual,

we had ambitious plans for the next day. Our intention was to devote most of it to an

exploration of the Sforza Castle.