Alphons Mucha, 1906

Alphons Mucha’s Slav Epic was considered by its creator to be the greatest work of his

career. It’s truly an epic, consisting of 20 gigantic paintings (the smallest are about

13 ft. x 15 ft., the largest 20 ft. x 26 ft.), painted between 1910 and 1928. The entire cycle

was painted with egg tempera, on enough canvas to shelter a small army (canvas was in fact in

short supply during some of the project, as the First World War could not be ignored). Its

subject is the history of the Slavic people.

The Magic of Words Triptych

Alphons Mucha was a man of many talents. In his youth, he was a talented singer. He was a member

of the choir of the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul in Brno until puberty intervened, after which

he continued working at the cathedral as a violinist. But he found himself drawn more to the

visual arts, for which he also had a talent. He found work as a scenery painter for theaters and

eventually as a creator of portraits and decorative art items. A Moravian nobleman, Count Eduard

Belasi, recognized Mucha’s talent and paid for him to receive training at the Munich Academy of

Fine Arts. In 1887, at the age of 27, he moved to Paris, where he received further training until

the count ended his subsidies in 1889. He was able to find work producing illustrations for

magazines and novels, and for a time shared a studio with the artist Paul Gauguin.

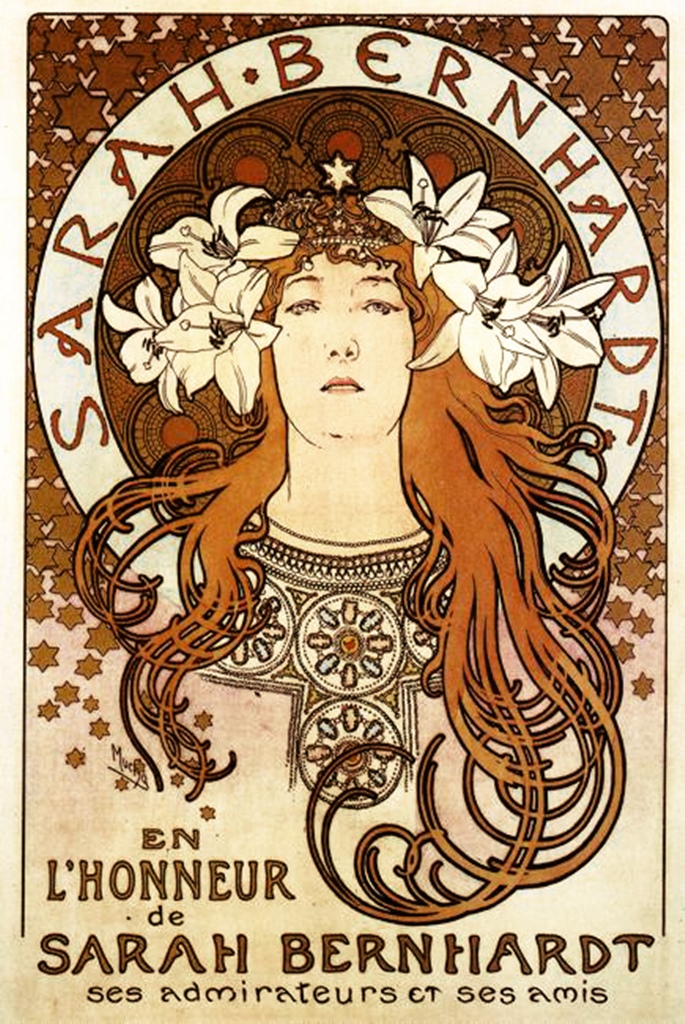

Late in 1894, Mucha received an unexpected boost to his career when the famous French stage

actress, Sarah Bernhardt, ordered new posters for her revival of the play Gismonda from the

publishing company Lemercier, on short notice. The regular Lemercier artists were unavailable

because of the holidays, but Mucha happened to be doing some work at the publisher correcting

proofs, and ended up being pressed into service. He came up with a unique poster that was an

immediate hit with the public, and copies of it were plastered all over the city. Bernhardt was

so pleased that she signed Mucha to a six-year contract. She also changed to a different firm for

the printing of her posters, F. Champenois, where Mucha was given steady employment at a generous

salary. Mucha would produce several Bernhardt posters while working at Champenois, featuring

Bernhardt in a variety of roles, including some male ones.

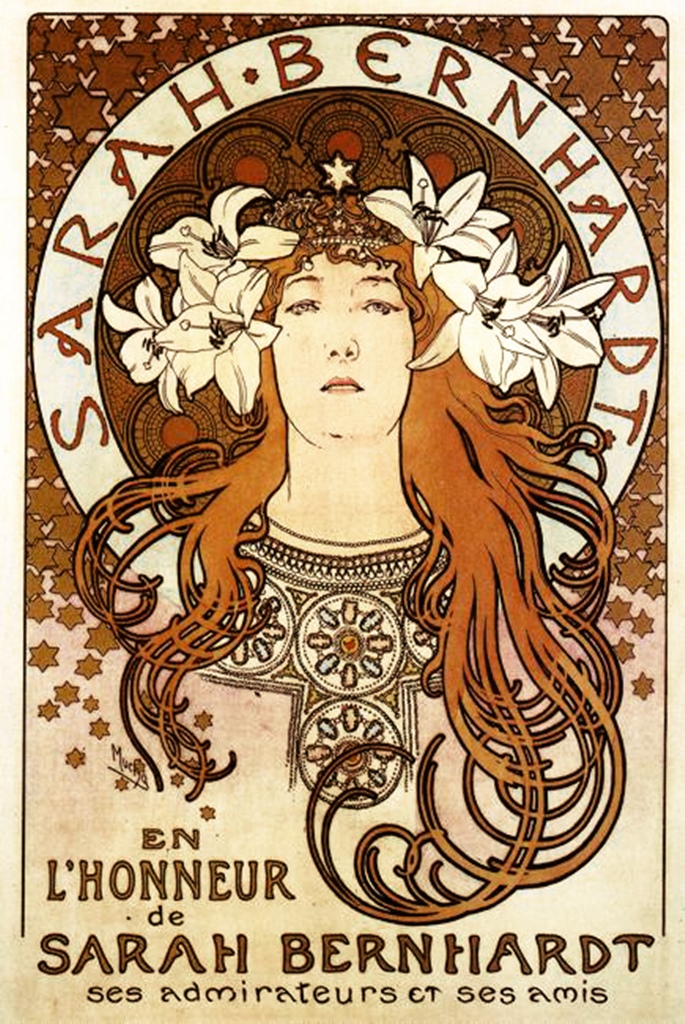

Sarah Bernhardt

Bernhardt as Gismonda, 1895

Bernhardt as Hamlet, 1899

Poster Honoring Bernhardt, 1896

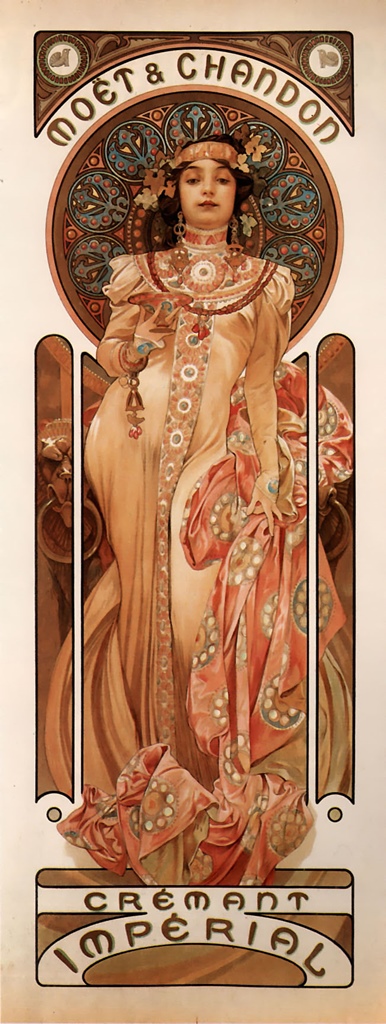

Mucha also created many advertising posters while at Champenois, producing more than 100 designs

between 1896 and 1904. His work was so well received that a retrospective exhibition of his work

was put together, which traveled to several European cities, and even to New York.

Ad for Champenois Publishing, 1897

Ad for Monaco Tourism, 1897

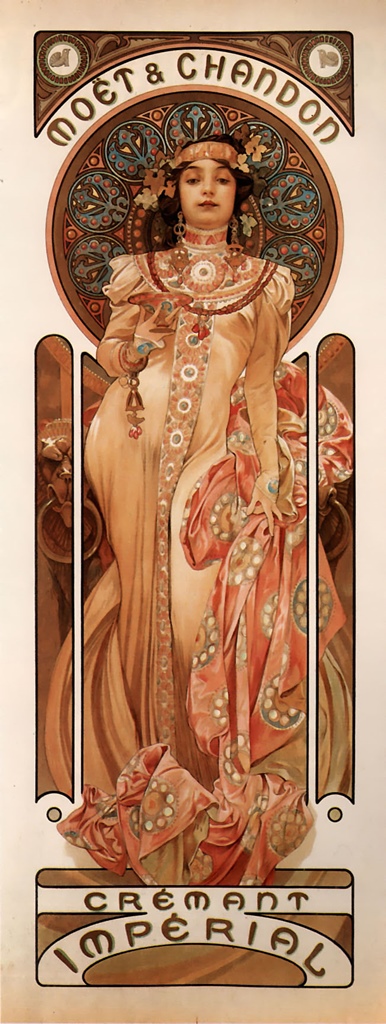

Ad for Moet & Chandon, 1899

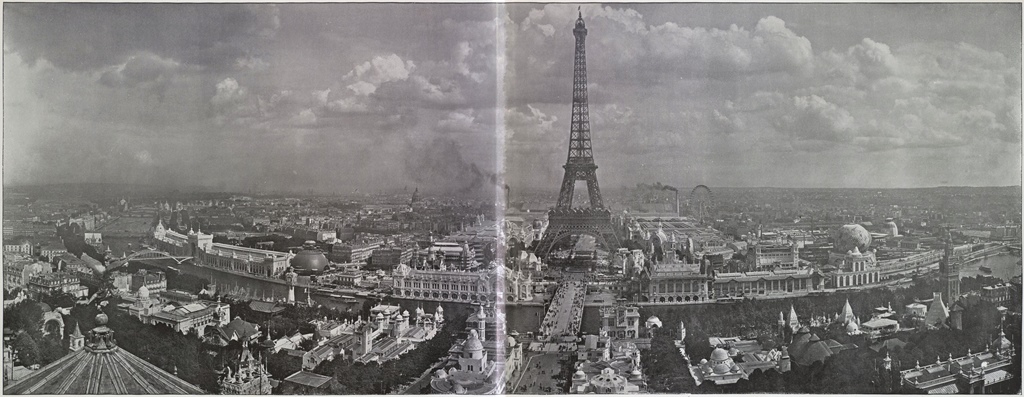

In 1900, Paris hosted the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, a large world’s fair that

featured (among many other things) pavilions for many foreign countries. Mucha did some

decorating work for the pavilions of Austria and Bosnia-Herzegovina, while also producing

some displays for the French jeweler Georges Fouquet. When he learned that he would be

doing this work, Mucha immediately left for a tour of the Balkan region, so he could gain

a better understanding of the costumes, architecture and customs of the Bosnia and

Herzegovina area. In addition to helping with his exposition work (which won him the title

of Knight of the Order of Franz Joseph I from the Austrian government), this also planted a

seed in his mind that would later grow into the Slav Epic.

Paris Universal Exposition of 1900

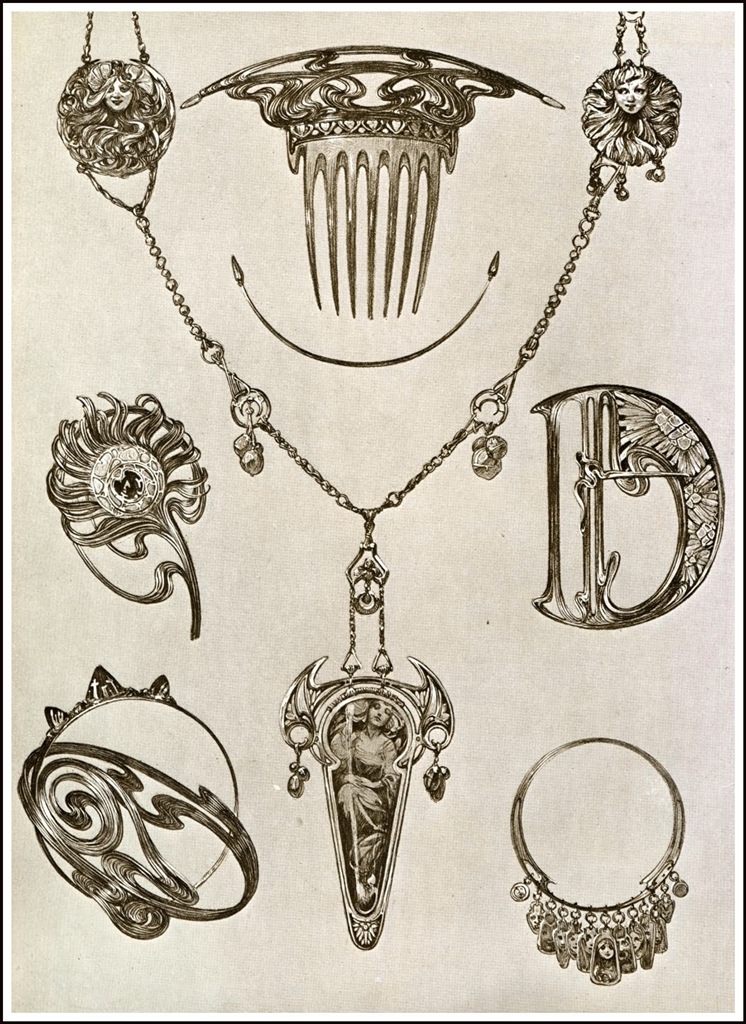

In the years following the Exposition, Mucha continued his advertising work, while trying

some projects in different areas. For example, he designed a store for Georges Fouquet, as

well as some items of jewelry.

Mucha-Designed Jewelry, 1901

In 1904, Mucha travelled to the United States, where he did some additional work, while also

doing some teaching and giving interviews (if he’d had any thoughts of being anonymous, they

were quickly dispelled – Sarah Bernhardt at the time was making annual trips to America, and

was taking her promotional materials along with her). Mucha ended up taking four more trips

to the U.S. over the next few years, in which he added a search for funding to his other

duties. In particular, he was looking for funding for the Slav Epic, an idea which

had germinated in his fertile mind. He eventually met the man who would become the project’s

principal sponsor, a businessman and philanthropist named Charles Richard Crane. He produced

a portrait of Crane’s daughter, Josephine Crane Bradley, which is considered to be the best

work he created while in America.

Josephine Crane Bradley as Slavia, 1908

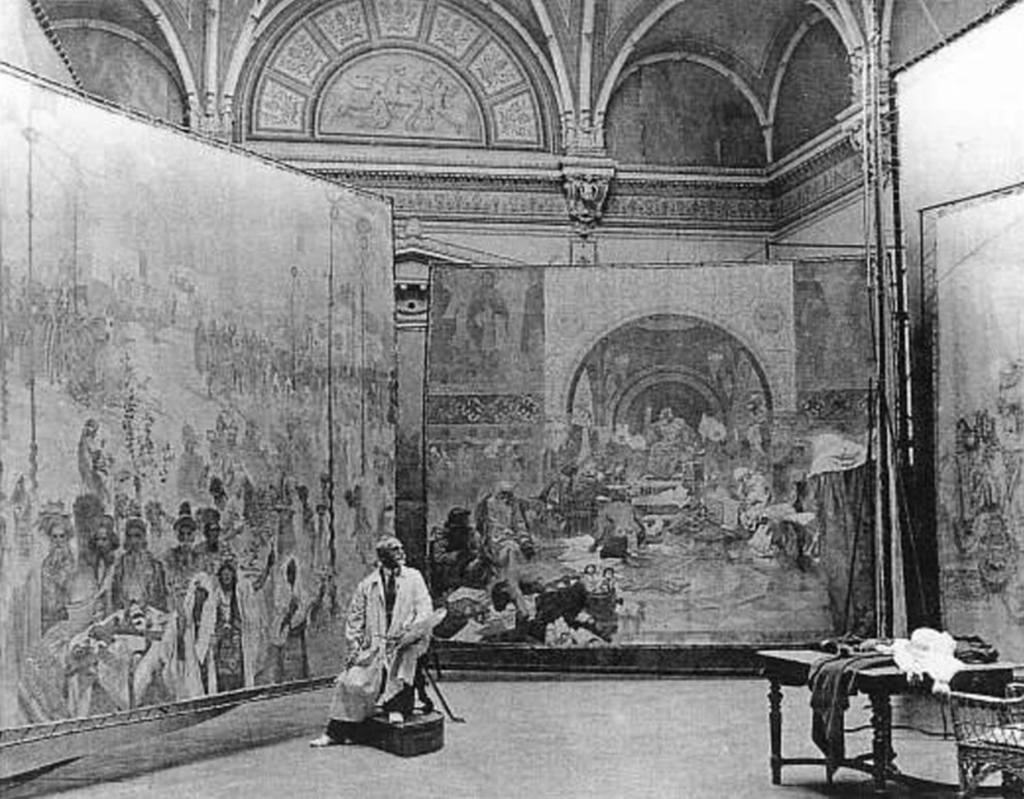

After getting Crane’s commitment to fund the project, Mucha returned to the country of his birth

in 1910. To prepare for the project, he travelled to all of the Slavic countries, from the

Balkans to Russia and Poland, where he made sketches and took photographs, using costumed models

to set the scenes he planned. Working on such gigantic canvasses obviously couldn’t be done in

an ordinary studio, so Mucha rented space in Zbiroh Castle in Western Bohemia, between Pilsen and

Prague. And he got to work, continuing through World War I and the birth of Czechoslovakia, and

finally finishing in 1926.

Mucha Working on Slav Epic, 1924

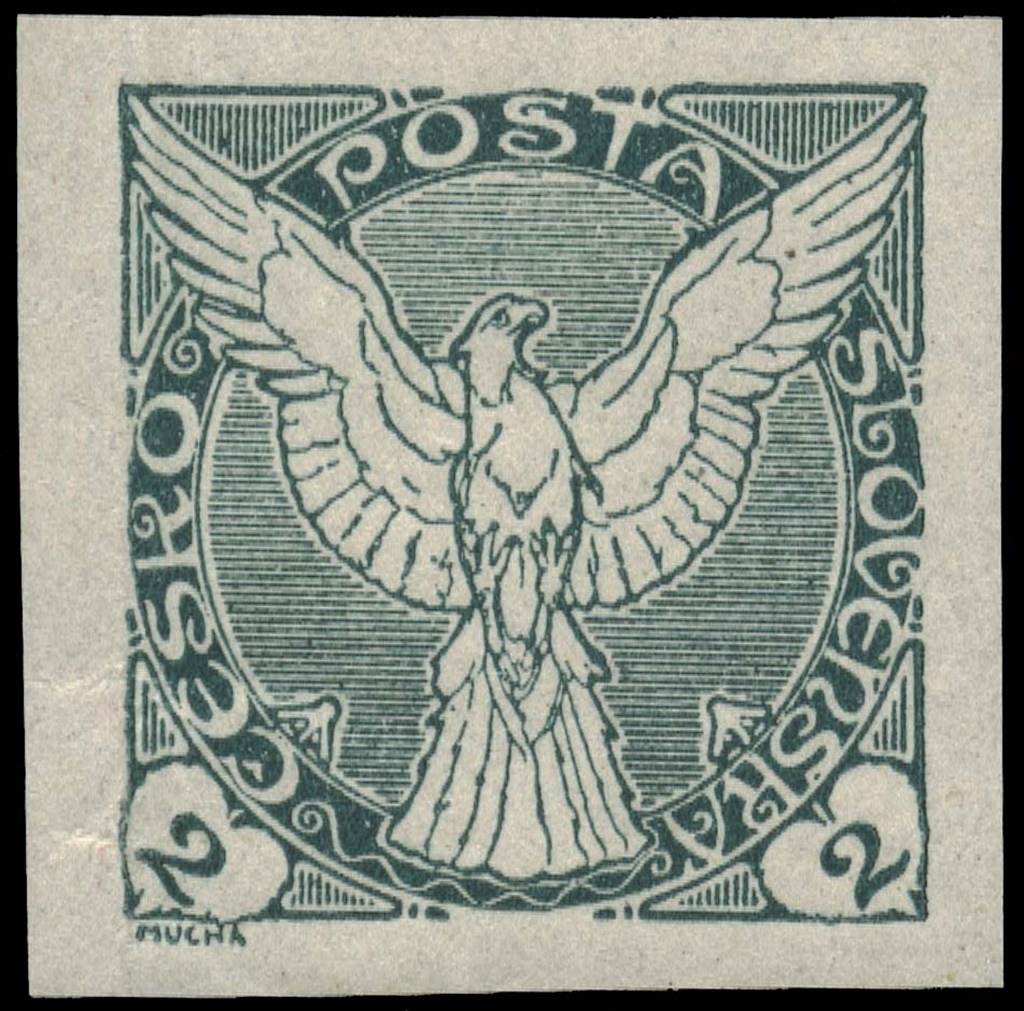

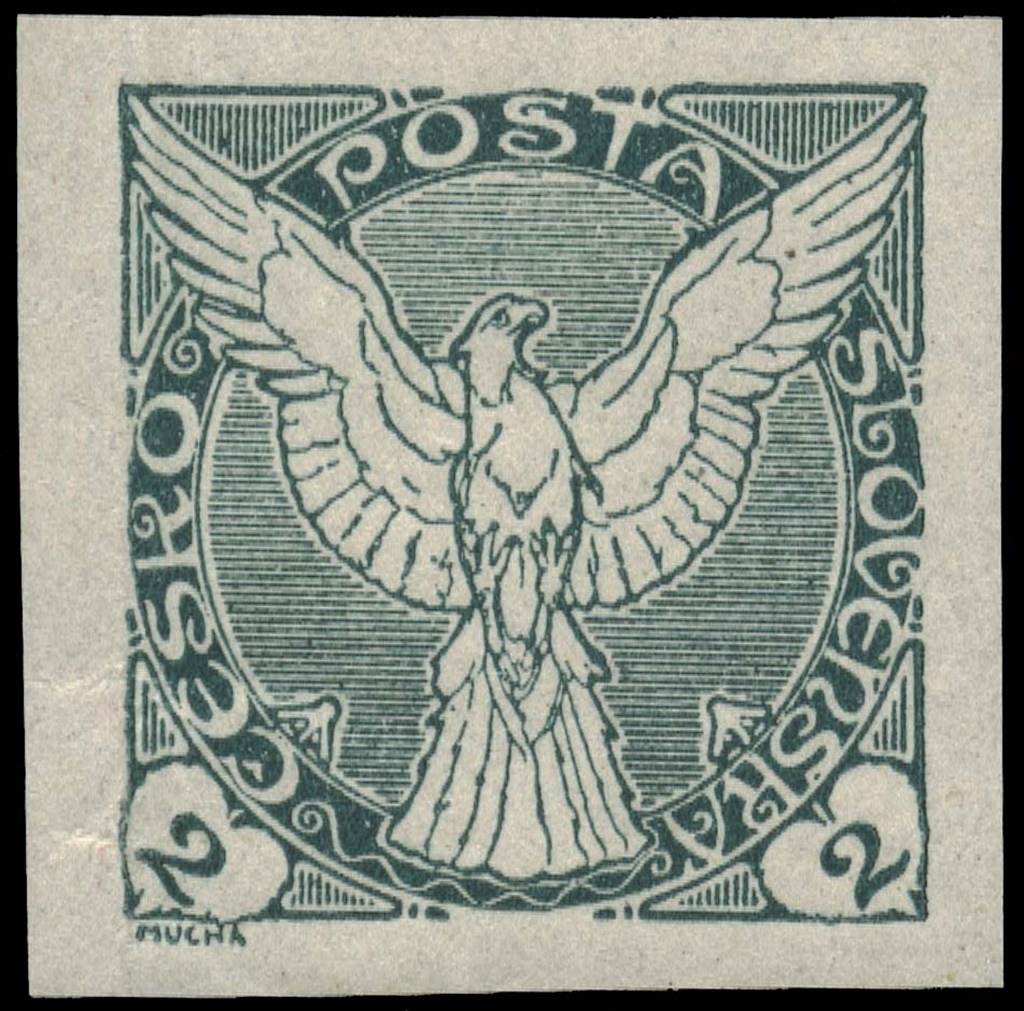

He did take a break when his new country asked for his help in designing money and postage

stamps in 1920.

Czechoslovak Money with Mucha Figures, 1920

Postage Stamp Designed by Mucha

There was a partial exhibit of the series in Prague in 1919, and then a full exhibit in 1928.

In 1921, five of the paintings were sent to the U.S. (probably a nod to Mucha’s sponsor) and

shown in New York and Chicago, where they received an enthusiastic reception. Perhaps surprisingly,

the reaction to the 1928 exhibition in Prague was more muted. While the cycle was appreciated,

their style was considered to be old-fashioned. Art had moved into new directions like

expressionism, cubism and surrealism, and Mucha was associated with art nouveau (a term he

never liked much), which was more turn-of-the-century.

Slav Epic Exhibition, 1928

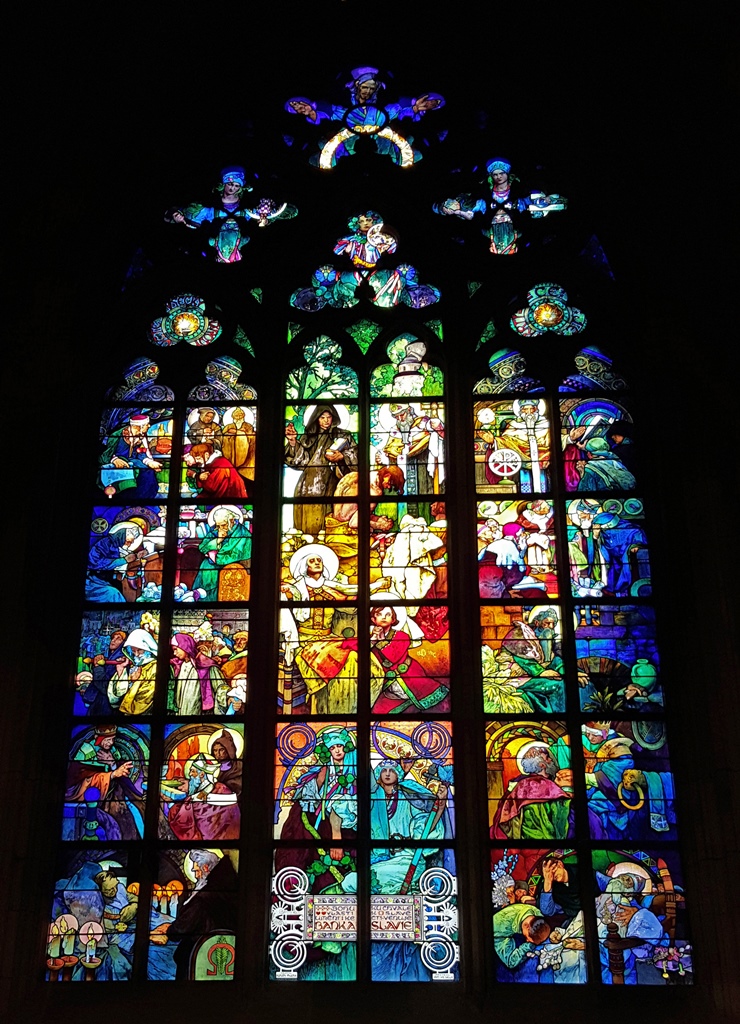

Mucha continued to work into the 1930s, but for the most part no longer received much attention.

He was asked to design a window for the St. Vitus Cathedral, which was completed in 1930 and

remains one of the cathedral’s most popular attractions.

Christ Blessing Slavic Nations Window, 1930

Mucha began work on a new historical series in 1936, but never completed it. There was a major

restrospective of his work in a Paris exhibition in 1936, with 139 of his works, included three

from the Slav Epic. But the political turmoil of the 1930s was a major distraction for

people from artistic matters, and in March of 1939 the German army marched into Prague. Mucha,

by this time 79 years old, was recognized as a Czech icon and a Slav nationalist, and was

arrested by the Germans. He was interrogated for several days and then released, but his ordeal

had caused irreparable damage to his health. He contracted pneumonia and died on July 14, 1939.

The Slav Epic was rolled up and successfully hidden from the Nazis during World War II,

though it was somewhat damaged in the process. After the war, the communist regime was

uninterested in the work, as it was considered decadent and bourgeois. Some of Mucha’s

proponents procured the cycle and did some restoration work on it. Eventually they put the

collection on display in 1963, in a castle in Moravský Krumlov, near the city of Brno. This is

where the paintings stayed until after the communists were kicked out, at which time Prague

became interested in bringing the paintings back. Prague requested the return of the paintings

in 2010, for restoration work and public display, but the move was blocked by the Mucha

Foundation (run by Mucha’s grandson John), as Prague didn’t have a suitable place for the

display. But in 2012 the paintings were taken to Prague, despite public protests, and put on

display in a space on the ground floor of the National Gallery’s Veletržní Palace. It was

removed at the end of 2016 pending the creation of a purpose-built venue to be dedicated to the

cycle’s display. There was a display of the cycle in Brno in 2018, but at its end it was put

into storage, and as of this writing, that is where it remains.

But in the summer of 2016, the cycle was still on display at Veletržní Palace, and that is where

we headed, catching a bus from near the Medieval Art Museum, where we’d spent the morning.

This involved crossing the river – the Vltava flows west-to-east here – into a neighborhood

outside the Old Town, which is more of a business district. We bought combination tickets,

which also allowed us to see the museum’s regular collection (see next page), and entered the

Slav Epic exhibit.

Most of the paintings in the Slav Epic depict specific historical events, in specific

places, and the locations are scattered around the Slavic world. But Mucha, being of Czech

origin, depicted Slavic history with an emphasis on Czech events. In the descriptions below,

I’ll group all of the Czech paintings together in historical order, in the interest of

continuity. A couple of the paintings are missing from those discussed, as we didn’t get very

good pictures of them (it was dark).

First up is The Slavs in Their Original Homeland, completed in 1912:

The Slavs in Their Original Homeland (1912)

This painting depicts a time (4th-5th Centuries) when the Slavic tribes were agricultural people

east of the Vistula River who were constantly under attack by Germanic tribes who would burn

their villages and steal their stuff. The people in the foreground are hiding in the bushes from

one of these attacks. The figures floating on the right feature a central pagan priest,

surrounded by figures symbolizing war and peace.

Next we have The Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy in Great Moravia, also from 1912:

Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy in Great Moravia (1912)

This painting depicts a critical time in the survival of Slavic languages, from the 9th

Century. By this time the Slavs had established the Moravian Empire, which covered the

present-day Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, and Christianity was catching on

throughout the empire, thanks to the efforts of German missionaries. A Slav Prince named

Rastislav engaged two monks, brothers named Cyril and Methodius, to translate the Bible

into Old Church Slavonic. German bishops opposed this move, insisting that Latin be used

exclusively. Methodius travelled to Rome to defend the translation idea and was able to

procure the approval of Pope Adrian II, who also made Methodius an archbishop. In the

process of the translation, the brothers devised the Glagolitic alphabet from which modern-day

Cyrillic (named for Cyril) is derived. Mucha’s painting shows the return of Methodius

(the bearded figure at center-left) to Moravia from Rome. A priest (at center-right) is

reading the pope’s letter to Rastislav’s successor, Svatopluk, who is seated on a throne.

The foreground figures floating at the right are the rulers of Bulgaria and Russia at the

time, who also supported Slavic Christianity, along with their wives, and the youth holding

the circle symbolizes the strength of the Slav people.

The next painting, from 1924, shows King Přemysl Otakar II of Bohemia:

King Premysl Otakar II of Bohemia (1924)

Otakar ruled Bohemia from 1253 until 1278, and spent much of that time forging alliances

among the Slavic monarchs who sat on various thrones at the time. This painting is set

during a wedding celebration between Otakar’s niece and the son of Hungary’s Béla IV, and

shows Otakar greeting two guests.

The next painting, from 1916, depicts Milíč of Kroměříž:

Milíc of Kromeríž (1916)

Jan Milíč of Kroměříž was a 14th Century Czech Catholic priest who held a number of influential

positions in the church, including within the Imperial Chancery of Charles IV. In 1363 he

resigned all of his positions so he could preach full-time. He could address followers in

Latin, Czech or German, and acquired a following in Prague, where he transformed a neighborhood

of ill repute into a benevolent institution called New Jerusalem. He also preached daily in

the Týn Church between 1369 and 1372. He started a Czech tradition of calling attention to

perceived evils in the Catholic Church, which did not endear him to some of the Church’s

authorities. He did, however, manage to avoid the fate that would later befall Jan Hus (see

below). In Mucha’s painting, Milíč is preaching to penitent prostitutes from atop the

scaffolding of New Jerusalem, and the prostitutes are trading in the garb of their profession

for nuns’ habits.

The next painting, completed in 1916, is called Master Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem

Chapel: Truth Prevails:

Master Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel: Truth Prevails (1916)

You may recall from earlier Prague pages that Jan Hus, like Jan Milíč, was a preacher who

questioned some of the practices of the Catholic Church and who gained a large following in

Prague by speaking to his audience in their own language. You may also recall that the

Catholic Church was less tolerant of this sort of thing in the early 15th Century and burned

Hus at the stake in 1415. The Czechs didn’t respond well to this and continued to promote

Hus’s teachings. The Holy Roman Emperor sent forces to Bohemia to suppress this behavior,

but the Czechs were able to resist these attempts in what came to be called the Hussite Wars.

All of which illustrates the fact that Jan Hus was the major ideological figure in a movement

known as the Czech Reformation, 100 years before Martin Luther. Mucha’s painting shows Jan

Hus preaching at his favorite place in Prague, the Bethlehem Chapel. The Chapel still exists,

sort of, in the southwestern part of the Old Town. It “sort of” still exists, as it had

fallen into disrepair and was turned into an apartment building in the 19th Century. It was

returned to its original state in the 1950s, but only some of the exterior walls are from the

original structure.

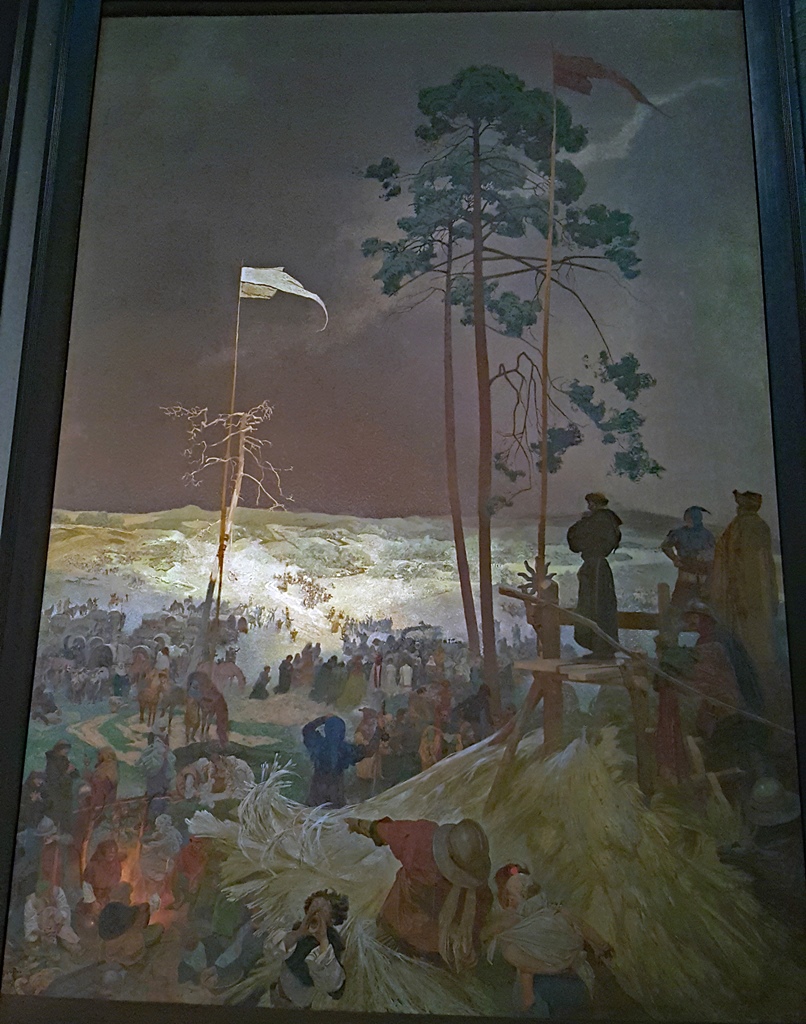

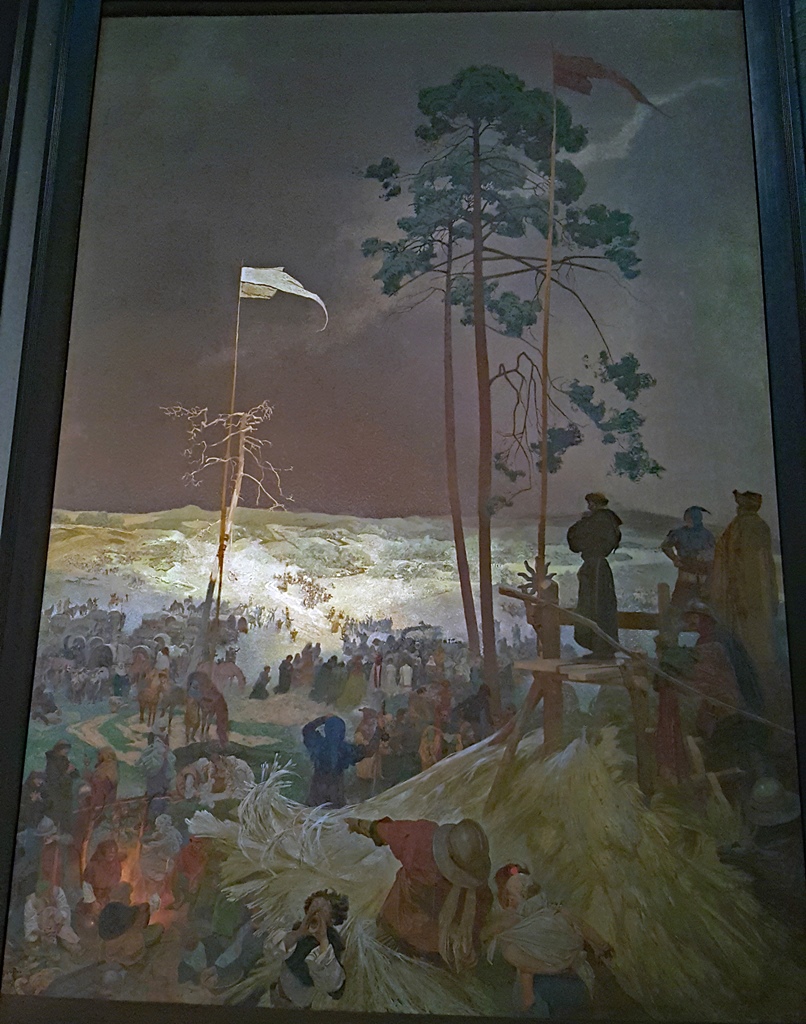

The next painting is called The Meeting at Křížky, and also dates from 1916:

The Meeting at Křížky (1916)

The painting depicts an episode from the beginnings of the Hussite resistance following the

execution of Jan Hus. The attempted suppression of the movement mentioned above was at

first largely confined to Prague, so in 1419, a large group of Hus’s followers gathered in

the town of Křížky, south of Prague, and a Hussite leader named Václav Koranda spoke to them,

encouraging rebellion.

Next up is a painting of Petr of Chelčice, from 1918:

Petr of Chelčice (1918)

This painting depicts a sad episode from the Hussite Wars. It seems that the town of Vodňany,

to the south of Prague, was attacked and conquered by the Hussite commander Jan Žižka around

1420, and refugees took their dead and injured to the nearby town of Chelčice. Petr of

Chelčice was a pacifist who lived there, and in the painting he is shown near the center with

a Bible under his arm, offering comfort to the victims and encouraging them not to seek

vengeance.

Continuing with the Hussite Wars, the next painting is The Hussite King Jiří z Podĕbrad,

from 1923.

The Hussite King Jirí z Podebrad (1923)

A break in the Hussite Wars began in the 1430’s, when Rome yielded (to a point) and decided to

allow the largest contingent of the Hussites (known as the Utraquists) to practice Christianity

in their own way (the major concession seems to have been allowing the laity access to

sacramental wine when celebrating the Eucharist). This was formalized in an agreement called

the Basel Compacts, finalized in 1437. In 1458, Bohemia elected a native Czech to be their king,

a man named Jiří z Podĕbrad (or George of Podĕbrady). In 1462, King Jiří sent a delegation to

Rome to get confirmation of his election and of the Basel Compacts from Pope Pius II.

Unfortunately, the Pope refused to recognize the agreement and sent a cardinal to Prague to

demand that the King outlaw the Utraquists. Mucha’s painting depicts the moment when the

cardinal (Cardinal Fantin, in the red robe left of center), made this demand. King Jiří, on the

right, is standing, as he has kicked over his throne in anger.

The next painting is called The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivančice, and was

painted in 1914:

The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivančice (1914)

The Bible of Kralice was a Czech translation of the Bible produced in the second half of the

16th Century by a small Hussite group known as the Unity of the Brethren. The first edition

was created in the town of Ivančice (also Mucha’s home town), but most of the printing was

actually done in the nearby town of Kralice, giving the translation its commonly-used name.

This was an important event in the preservation of the Czech language, and the Bible has been

the most popular Czech translation until the present day.

The next painting is called The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree, and was

last worked on in 1926. This painting was never completed – one can see that many of the

background characters’ faces have not been filled in yet:

The Oath of Omladina under the Slavic Linden Tree (1926, unfinished)

The event depicted in this painting depicts members of the Omladina organization, which was

founded in the 1890’s. Omladina was a nationalist youth organization that favored Czech

independence from Austria-Hungary. In the painting, Omladina members are pledging their

allegiance to the goddess Slavia, who is a symbol of Slavic unity and is sitting in the

linden tree in the background. Two of the children in the foreground are modeled after

Mucha’s children.

Moving to paintings set in areas outside the Czech homeland and depicting non-Czech Slavs,

we’ll start with this one, called The Celebration of Svantovít, finished in 1912.

The Celebration of Svantovít (1912)

As Slavs migrated west from their original homeland, they broke up into different groups. One

such group was known as the Rani, and they headed farther north and west than the other

groups, ending up settling in the 9th Century on an island just off the Baltic coast of present-day

Germany, now known as Rügen (this is actually Germany’s largest island). The Rani were able to

become highly influential, through a combination of a strong navy and a strategic location. But

eventually their neighbors caught up with their military capabilities, and the Rani were conquered

by Denmark in 1168. They were forced to renounce their pagan beliefs and embrace Christianity, and

over time they were “Germanized”, with their culture and language disappearing by the 15th Century.

Mucha’s painting depicts a scene from the Rani empire at its height, when pilgrims would come to

Rügen to celebrate an annual autumn festival dedicated to the pagan god Svantovít. The figures

floating at the top are some of the pagan gods, preparing for a struggle against the wolf pack

representing the Danes and their culture.

The next painting is The Holy Mount Athos, completed in 1926:

The Holy Mount Athos (1926)

Mount Athos, located on a peninsula in northern Greece, was the center of the Greek Orthodox

Church, the branch of Christianity that resonated most with southern Slavs. Mucha’s painting

depicts a scene in a Greek Orthodox Church where a procession of Russian pilgrims is waiting

for a chance to touch one of the holy relics being held by the four priests in the background.

The figures hovering above the procession are angels, holding models of Slavic monasteries

which were nearby.

The next painting depicts Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria, and was completed in 1923:

Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria (1923)

In the Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy in Great Moravia painting above, the

translation of the Bible into Old Church Slavonic had been approved by Rome in the 9th Century,

and work proceeded on the project in Moravia, under Archbishop Methodius and Prince Svatopluk.

However, Methodius eventually died, in 885, and at that time Svatopluk withdrew his support

from the project and evicted the scholars who’d been working on it. This put the project (and

the future of Slavic languages) in doubt, but the scholars were able to find support in

Bulgaria, under Tsar Simeon I, and the project was able to continue.

Next, we move on a few centuries to The Coronation of Serbian Tsar Štěpán Dušan,

completed in 1926:

The Coronation of Serbian Tsar Štěpán Dušan (1926)

Štěpán Dušan was a Serbian king who conquered a big piece of southeast Europe in the 14th

Century. He enacted a constitution for his empire (with its capital in Skopje, now the capital

of North Macedonia) and built monasteries, and his reign is considered to be the peak of the

Serbian Empire. After his death in 1355, the empire pretty much collapsed beneath the forces

of the advancing Ottoman Empire. Mucha’s painting shows an episode in 1346 in which Štěpán

elevated himself from King to Tsar. The procession following the coronation is depicted.

Moving on another century and northward up to Poland, the next painting, completed in 1924, is

called After the Battle of Grunewald:

After the Battle of Grunewald (1924)

The Battle of Grunewald was fought on July 15, 1410 between a Polish/Lithuanian alliance and

the German Order of the Teutonic Knights. The Knights were a crusading military order which had

been spreading Christianity for 200 years. Conversion to Christianity was not an immediate

factor in the battle, as all of the forces involved were already Christian by this time

(Lithuania had been the last pagan country in Europe, but had converted in 1387 after their

Grand Duke Jogaila had married Queen Hedwig of Poland; at this time Jogaila had become King

Władysław II of Poland). The battle was based more on territorial claims and trade disputes.

In any case, the battle was won by the alliance, and the Teutonic Knights would never enjoy

their former power again. Mucha’s painting is set the morning following the battle and depicts

Władysław reacting in horror to the battle’s casualties (casualty estimates vary, but there

were certainly several thousand).

The next painting is set in the 16th Century, and is entitled The Defense of Sziget by

Nikola Zrinski (completed in 1914):

Nella with The Defense of Sziget by Nikola Zrinski (1914)

Szigetvár is a town in southern Hungary which in 1566 held a fortress that stood in the way

of the Turkish army under Suleiman the Magnificent, which was advancing with the intention of

attacking Vienna, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. The vastly outnumbered defending

forces were commanded by a Croatian-Hungarian nobleman named Nikola Zrinski. The defenders

were able to hold off the invaders during a siege that lasted about a month, but eventually

the fortress was overwhelmed, with great casualties on both sides (including both commanders).

But while the Turks won the battle, their advance toward Vienna was stopped, and they would

not threaten again until 1683’s Battle of Vienna (which they would lose, essentially ending

their threat to the Christian world). Mucha’s painting shows an incident that took place in

Szigetvár, in which Zrinski’s wife Eva (on the right), seeing that the Turks had captured the

city, set fire to the city, resulting in the deaths of many Turkish soldiers (and of many of

the city’s inhabitants).

The next painting was completed in 1914 and depicts The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia:

The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia (1914)

In 1861, Emperor Alexander II of Russia issued an edict which emancipated Russian serfs who

lived on private land. Under serfdom in Russia, 23 million peasants (approximately 38% of the

population) were not allowed to leave the property on which they were born, and were obligated

to make regular payments in labor and goods (about a third of their income) to the owner of the

land on which they lived. They were also not allowed to marry without the landowner’s permission.

Under the edict, the serfs were relieved of these obligations and acquired the rights to own

property and to run their own businesses. They were also given the right to buy land from the

landowners. Mucha’s painting depicts a crowd in Moscow (with St. Basil’s Cathedral and the

Kremlin in the background) who have just heard this announcement and who are reacting with

uncertainty as to what it means for the future (still in doubt when this painting was completed;

the monarchy wouldn't be abolished for another three years).

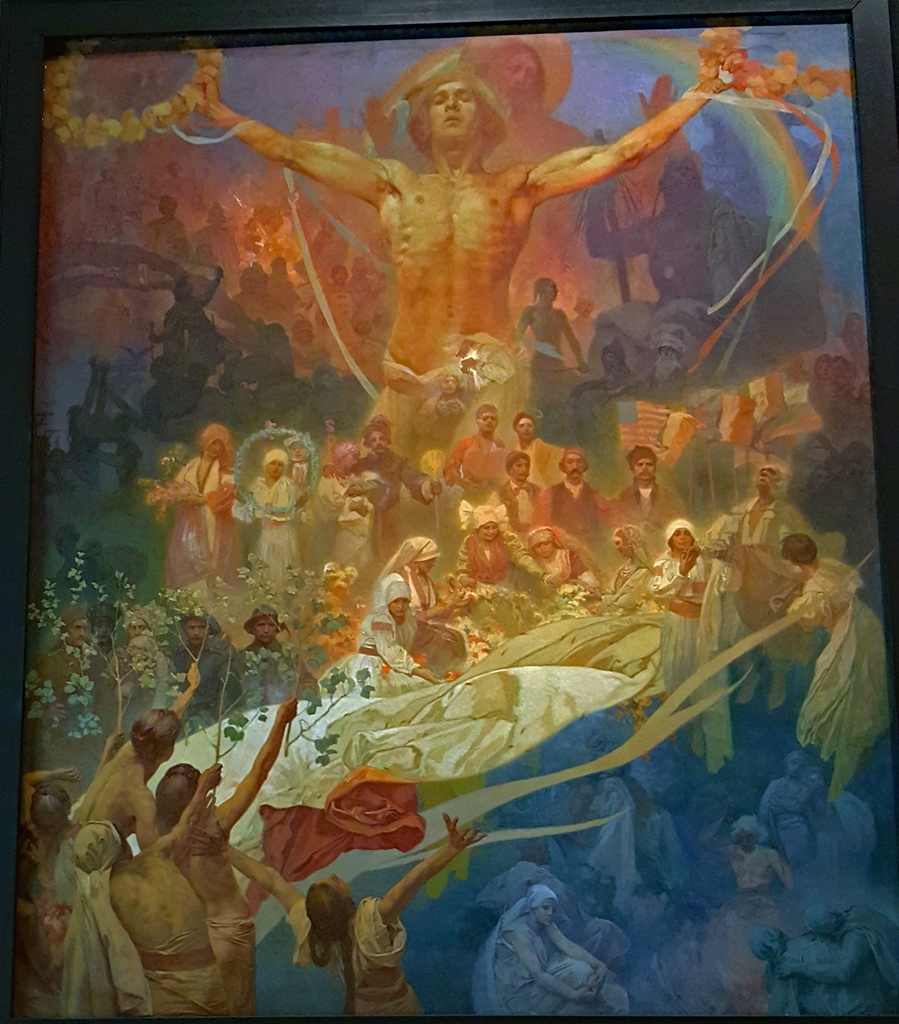

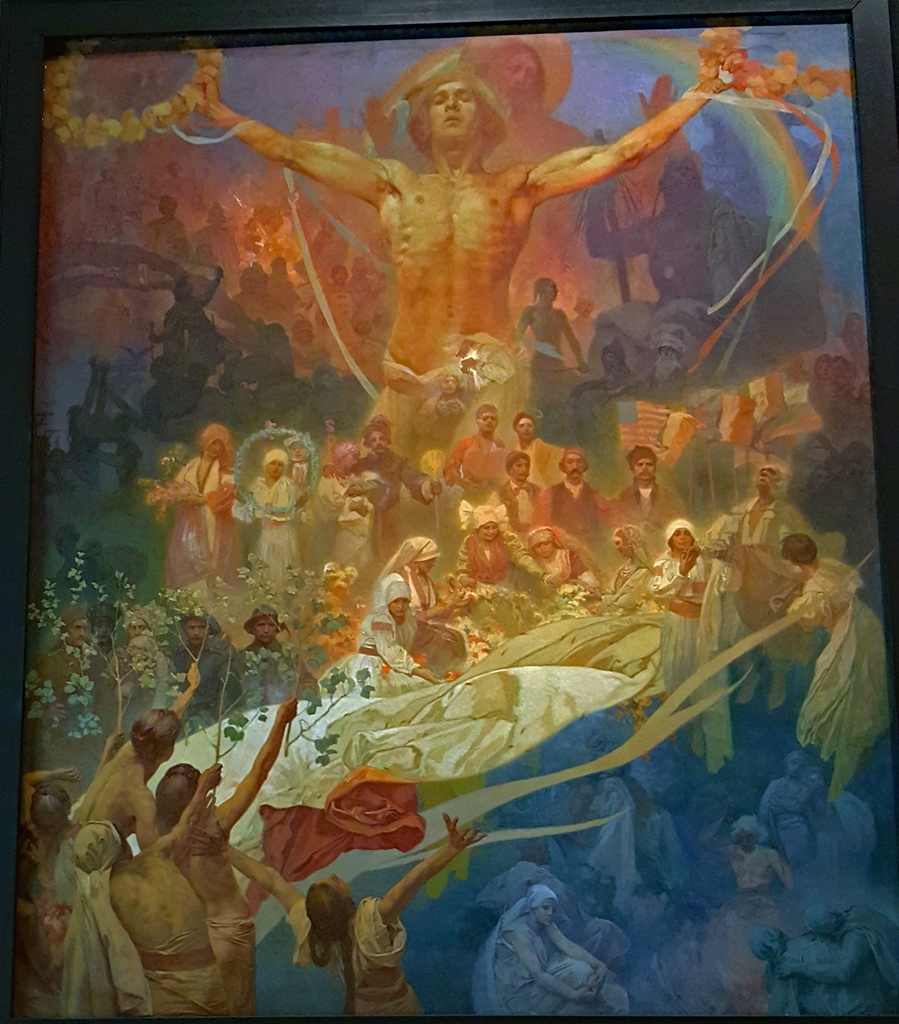

The last of the paintings in Mucha’s series is The Apotheosis of the Slavs: Slavs for

Humanity, completed in 1926:

The Apotheosis of the Slavs: Slavs for Humanity (1926)

In this painting, Mucha brings together the themes from all of the other paintings and

presents hope for the future of the new Czechoslovak nation. In the bottom right, there are

scenes from the early years of Slav history. In the top background, the struggles of the

Slavic peoples are alluded to. In the brightly-lit middle are figures of Czechoslovak

soldiers, returning to their homes from World War I. And the bare-chested guy in the middle

represents the new nation, with a Christ figure guiding from behind.

After having our fill of the Slav Epic, we headed for the Veletržní Palace’s regular

collection. It was easy to find, as it was just upstairs. And we already had tickets.