On our last full day in Prague, we planned on visiting museums. We hadn’t really made the rounds

of Prague museums yet – there were a couple of small ones at Prague Castle, but those were the

only ones we’d seen so far. Mostly we’d been looking at churches. First on our museum itinerary was the

Museum of Medieval Art,

located in the northern part of the Jewish Quarter. We took tram 6 from Wenceslas Square to the

Dlouhá třída stop, which was a short walk from the museum.

Hanging Sculpture at Dlouhá and Rybná

Buildings at Kozí and Haštalská

Entrance to Convent of St. Agnes

In some ways, visiting the Medieval Art Museum was a lot like visiting another church. Not

only were nearly all of the items on exhibit religious in nature, but the museum itself was

located in the buildings of the former Convent of St. Agnes. The convent was founded by St.

Agnes herself, then known as Agnes of Bohemia, around 1231. Agnes was the daughter of King

Ottokar I and the sister of King Wenceslaus I. Her father had tried more than once to marry

her off to European royalty, including to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, but when Ottokar

died in 1230, she decided (with the support of Pope Gregory IX) to devote her life to prayer

and spiritual works. Around this time, Agnes heard about Clare of Assisi and her Order of

Poor Ladies and decided to establish a “Poor Clare” community of nuns at a new convent she

was founding. She corresponded with Clare herself and was able to have her send five nuns

to get the community started. Agnes became a Poor Clare nun herself in 1236 and tended to

lepers and paupers in a hospital attached to the convent, even after she became abbess in

1237. Agnes died in 1282, at which time she was already considered a saint by her followers,

but she didn’t formally become a saint until she was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1989.

She is revered by the Czechs, and they have put her on their money.

St. Agnes on a 50 Koruna Note

After Agnes died, the convent diminished in importance, as King Wenceslas II established a new

monastery in Zbraslav, which became the focus of royal attention. Some new work was done on

the convent as part of Charles IV’s rebuild of the city in the 14th Century, but the convent

otherwise began a long and steady decline. During the Hussite Wars of the 15th Century, the

convent was pressed into duty as an armory and a mint. The convent was dissolved by Holy

Roman Emperor Joseph II in 1782, and for a time it was used as housing for poor people,

workshops and storage. Early in the 20th Century, a group came together to renovate the

convent, and work proceeded until World War I broke out. In 1963, the National Gallery

acquired the convent and continued the renovation work. The convent opened as a gallery of

19th and 20th Century Bohemian art in 1978, but in 2000 it was converted to a museum of

medieval Bohemian and central European art, mostly using a collection that had been kept in

the monastery attached to the St. George Basilica at Prague Castle.

The Convent of St. Agnes

On entering the convent, we decided to look at the convent part before getting started on the

art collection. There are two church buildings in the convent. One is devoted to St. Francis,

and is the oldest church in the convent. It once had a dome, but the dome collapsed and a new,

somewhat modern-looking slanted roof was added. It is sometimes used for concerts, but it was

closed off during our visit. On the way to discover this, we passed a room that was once used

as a refectory (dining hall), among other things.

Bob in Convent Hallway

Convent Refectory

Door to Church of St. Francis

The other church is called the Church of St. Salvator, or the Church of Christ the Savior.

It was built between 1270 and 1280 in the French Gothic style, and is relatively intact.

Nella and Church of Christ the Savior

Church of Christ the Savior

Nella in Church of Christ the Savior

It’s thought that St. Agnes and her brother Wenceslas I are both buried somewhere on the

grounds, but the locations of their tombs are unknown. A funerary marker that looks like

an indicator for the tomb of St. Agnes has been found, but not near anything that looks

like a tomb.

Funerary Marker of St. Agnes

This seemed to be most of what there was to see in the non-museum part of the convent,

so we headed over to the museum entrance to see the medieval art on display.

Bob Inspecting Medieval Paintings

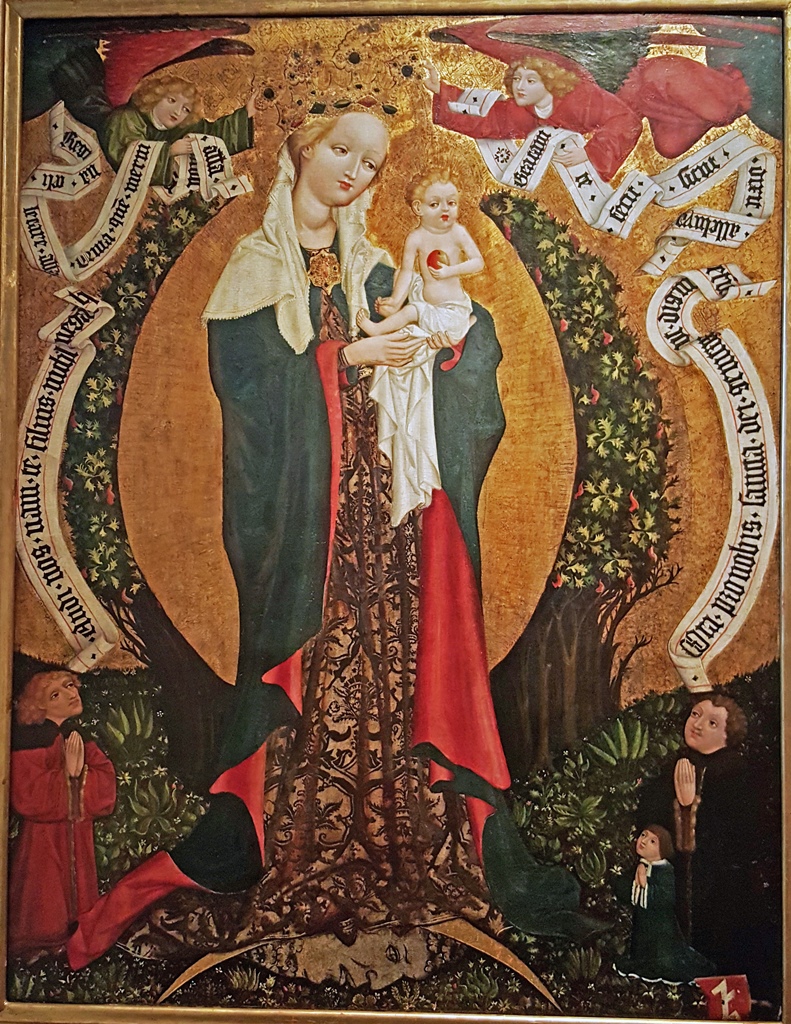

The artworks displayed in the Museum of Medieval Art mainly include paintings, sculptures and

woodcarvings. They are mostly from the 14th and 15th Centuries and are stylistically

pre-Renaissance. Record keeping during that time appears not to have been very

good, so the posted dates of the artworks are nearly all approximations, and the artists are

generally not known. Most of the works are attributed to a city and church, though some are

attributed to the “Master of x”, where x is the name of the artwork (e.g. “the St. George

Altarpiece”). This is a cute way of attributing the creation of an artwork to the person who

created it (hard to argue with, but not exactly informative). Virtually all of the artworks of

the time depicted religious scenes, of which a few are obvious favorites. Some might find this

apparent lack of variety uninteresting, but others might find interest in the different

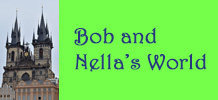

approaches of the anonymous artists to well-worn subjects. For example, here are several works

involving the Virgin Mary:

Madonna from the Franciscan Monastery (Prague, ca. 1350)

Madonna of Žebrák (ca. 1380)

Variant of the Madonna of Ceský Krumlov

Seated Virgin Mary (1475-80)

St. Anna with the Virgin and Child (ca. 1520)

Madonna of Roudnice (ca. 1385)

The Assumption from Deštná (ca. 1450)

Assumption from Bílá Hora (ca. 1440-50)

Annunciation (ca. 1460)

Altarpiece from Velhartice (ca. 1500)

The Roudnice Altarpiece (ca. 1410)

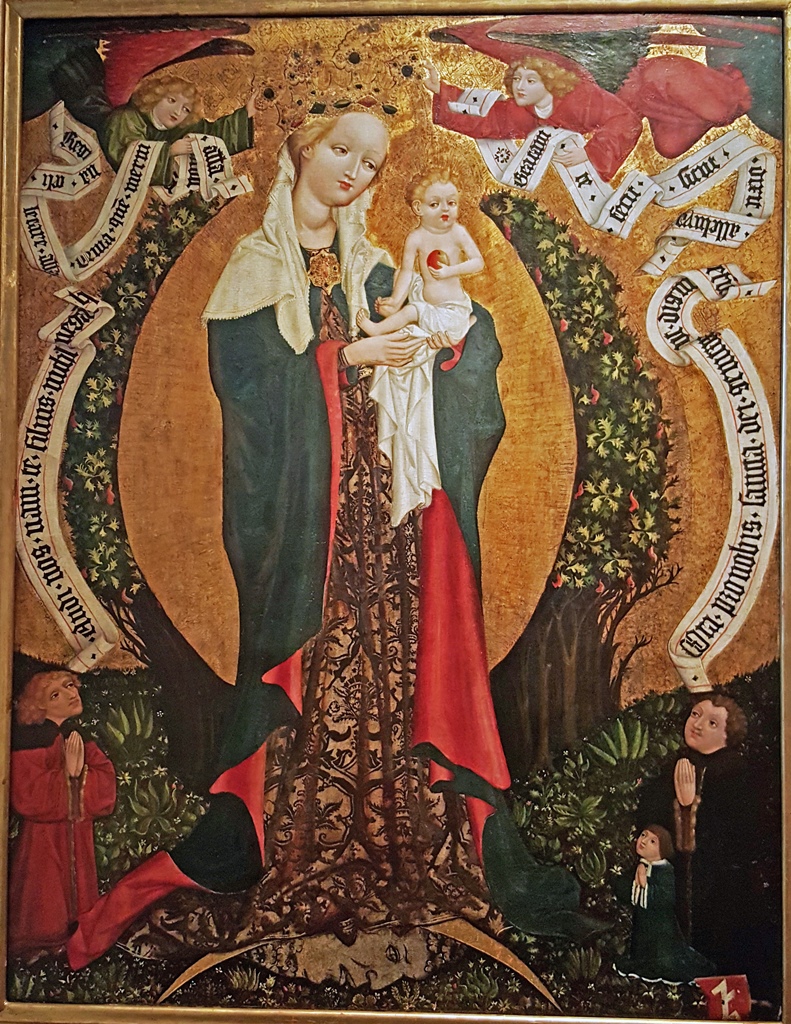

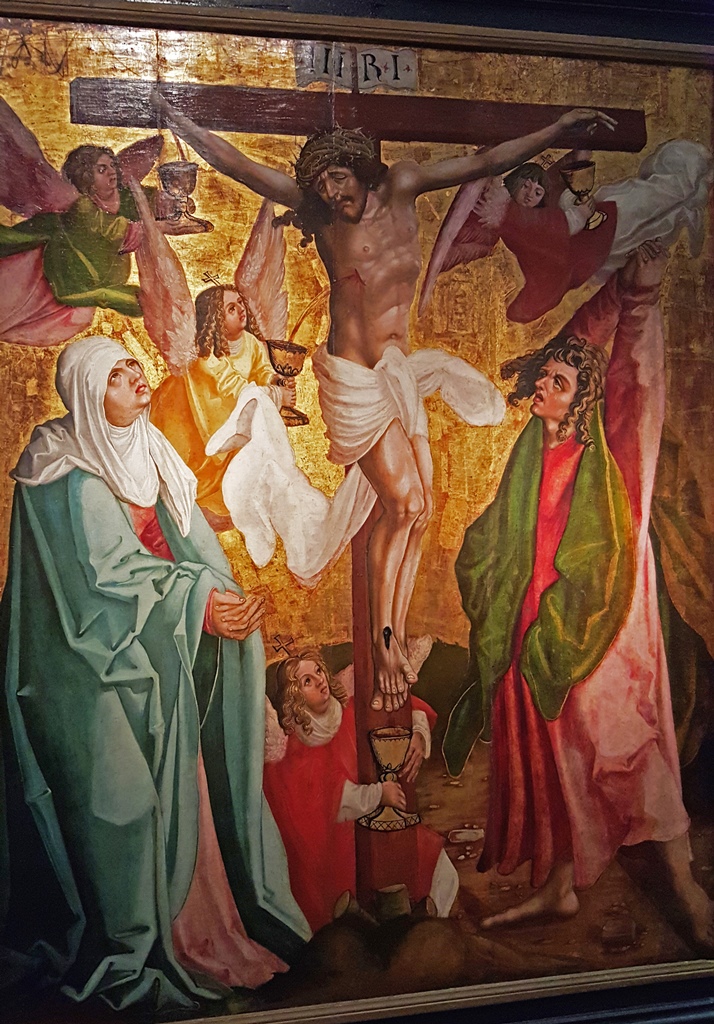

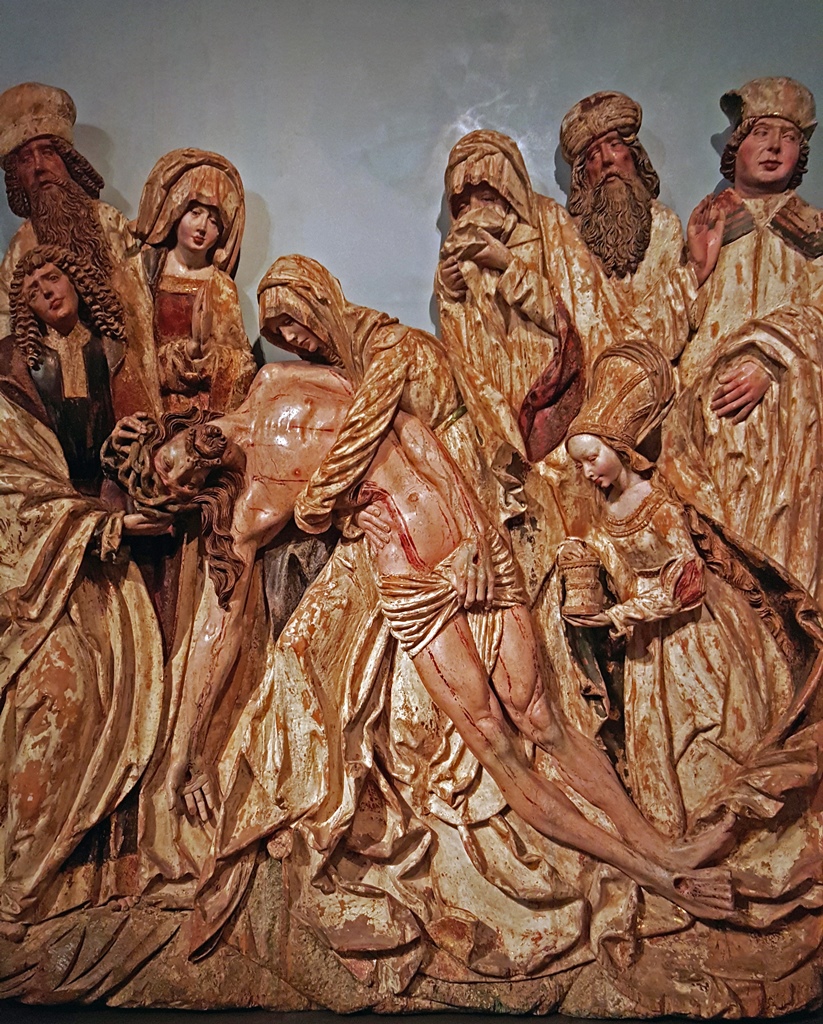

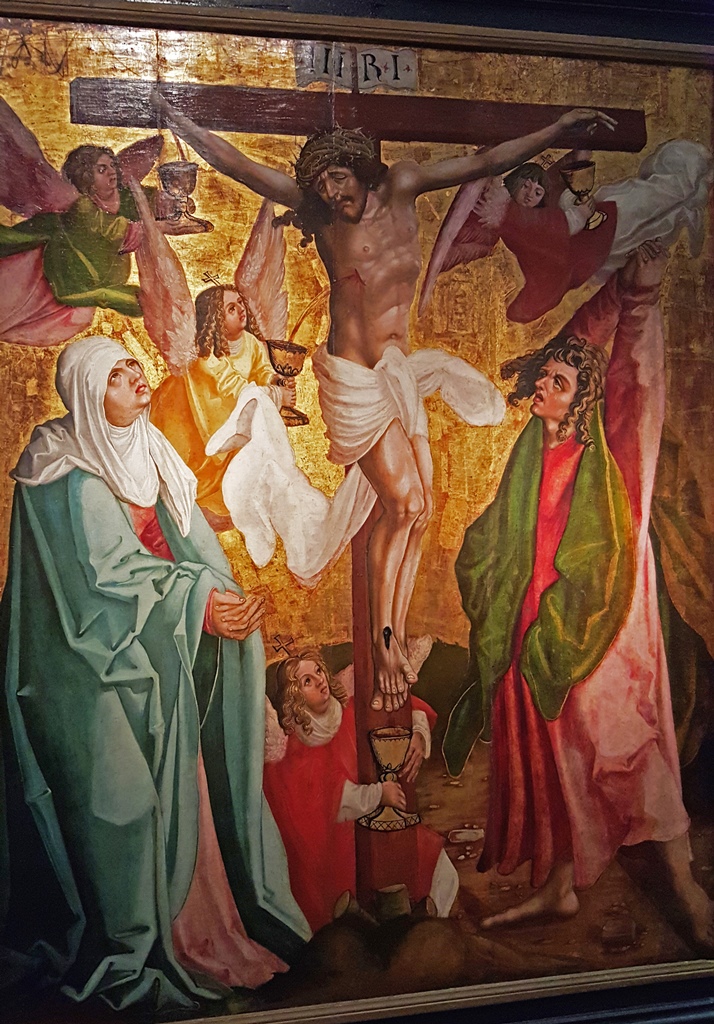

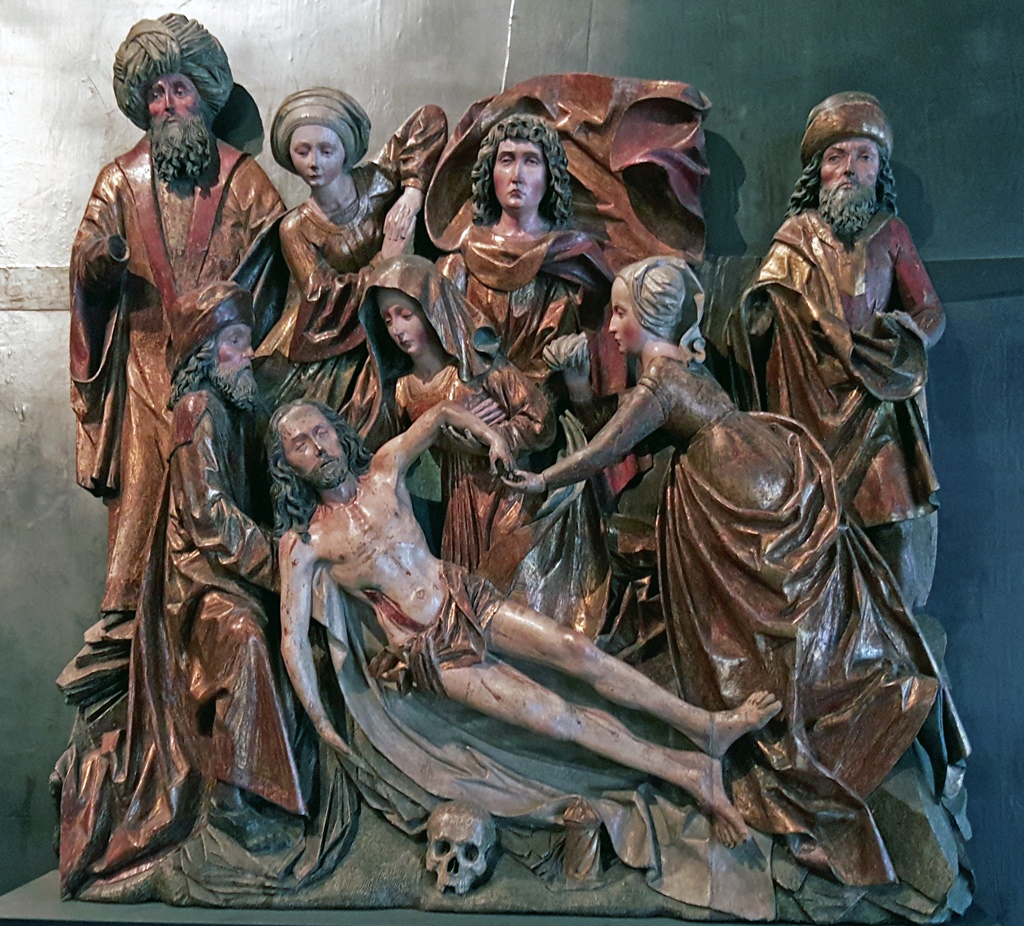

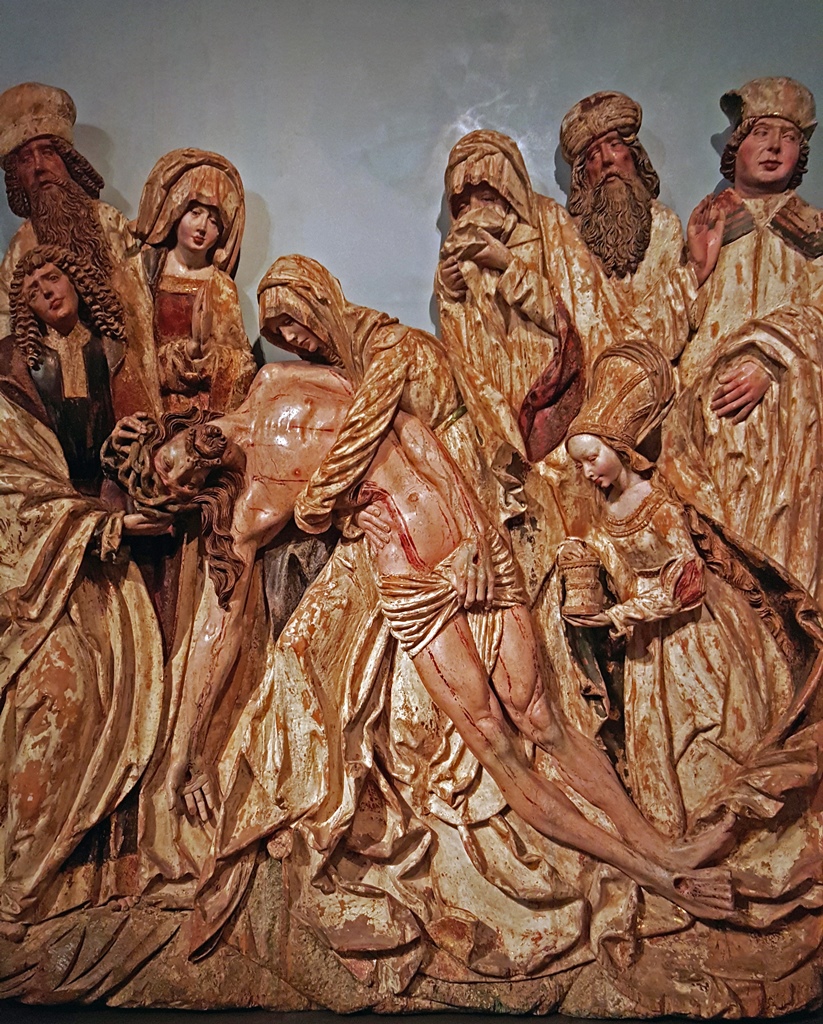

Here are works related to the Passion of Christ:

Christ with Crown of Thorns (ca. 1475)

The Melník Crucifixion (ca. 1510)

Reininghaus Altarpiece (ca. 1430)

Altarpiece from Záton (ca. 1430)

Lamentation (ca. 1480-90)

Lamentation from Žebrák (ca. 1500-10)

Altarpiece (ca. 1480) and Nicodemu/Christ Sculpture (ca. 1510-20)

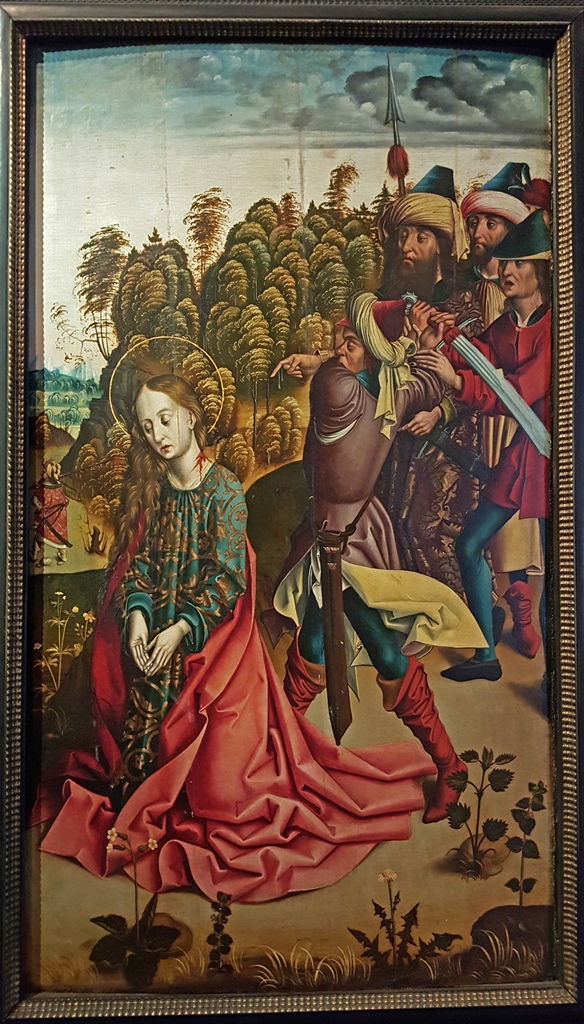

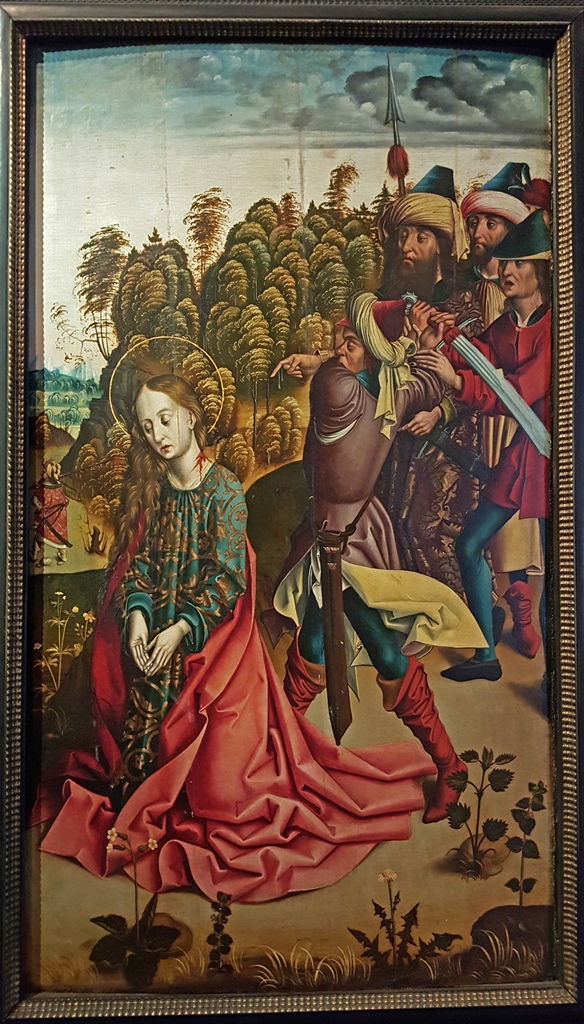

Other favorites involve saints, frequently alluding to their martyrdoms. Here are a few saint works:

St. Cunigund of Stanetice (ca. 1365-70)

St. Ulrich (ca. 1380-90)

Beheading of St. Barbara, Hans Pleydenwurff (ca. 1470)

Beheading of St. Barbara (ca. 1480-90)

There are also some random religious articles on display:

Orators - Fragments of Madonna the Guardian (ca. 1500)

Chasuble with Figure of St. Adalbert (ca. 1400)

There was one painting that seemed out of place. It’s more Renaissance in style, and does

not depict a religious subject – it seems to just be a portrait. A glance at its distinctive

style reveals it to obviously be a work of Lucas Cranach the Elder, but more than a glance

(using technological tools) contradicts this assessment, as the preparatory work detected by

a thorough examination does not match up with Cranach’s known methods. For this reason, the

portrait is attributed to a follower of Cranach.

Portrait of a Young Lady with a Fern, Cranach Follower (ca. 1538)

After getting through the museum’s collection, we left the convent and moved on to our

next museum for the day, the Veletržní Palace, where we started by spending some time

going through Alphons Mucha’s monumental series of paintings known as The Slav Epic.