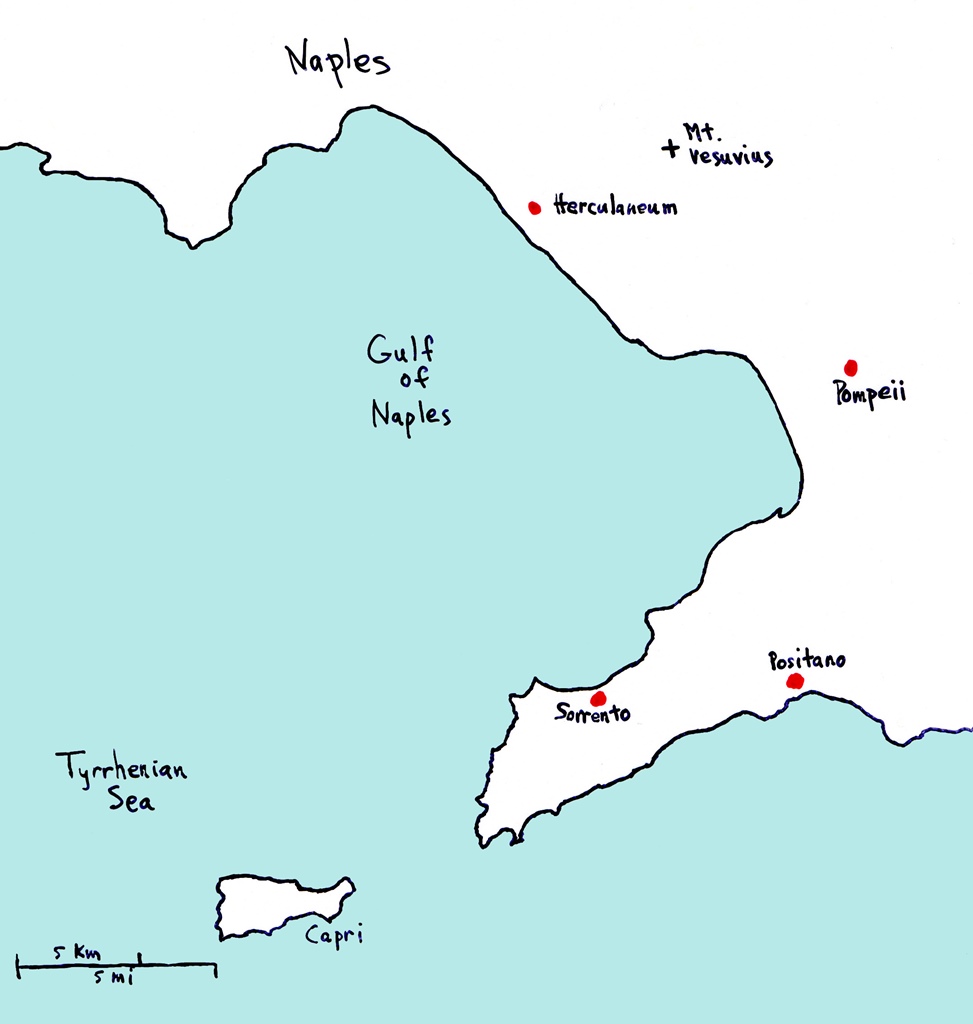

Gulf of Naples Area

The city of Pompeii was a bad place to be on August 24 in the year 79 AD. Things started out

pleasantly enough, with the citizens of this Roman city of 20,000 going about their business

as usual. Establishments such as bakeries and restaurants were serving their customers, and

carts wheeled up and down the paved streets, making their deliveries. Other businesses, such

as public baths and brothels, were also supplying their popular services. Around the city,

repairs were still ongoing from a devastating earthquake which had struck the area seventeen

years earlier. But there was light at the end of the tunnel, and many of the industrious

residents had even found the time to decorate their homes with colorful paintings and

mosaics. But then the mountain blew up.

Mt. Vesuvius

Mt. Vesuvius, located a short distance to the northwest of Pompeii, is now known to be a volcano

of frightening potential. It is considered to be the only active volcano on the European continent

(two other volcanoes, Etna and Stromboli, are on islands). All three volcanoes were formed hundreds

of thousands of years ago as a result of the subduction of the African tectonic plate beneath the

Eurasian tectonic plate. Vesuvius has been erupting off and on for several thousand years, but it

had been quiet for hundreds of years before 79 AD, apparently pausing to build up pressure. But

because of this prolonged period of inactivity, Vesuvius was not generally considered to be

anything other than a garden-variety 6500-foot mountain, though it did have some remarkably

fertile soil on its slopes.

So one can easily imagine profound surprise among the Pompeiians in the early afternoon of August

24 when a humongous blast was followed by the appearance of a thick column of ash, pumice and

other volcanic debris rising several miles into the sky. Unfortunately for Pompeii, the prevailing

winds in the area blow toward the southeast, and August 24 was not atypical in this respect. So

when gravity took over and the material blown skyward began to fall earthward, it did not land on

Naples, which was about the same distance from the mountain but to its northwest, but instead

started falling onto communities to the southeast. Like mainly Pompeii. To the unfortunate people

in this afflicted town, this meant the blotting out of the sun and the beginning of a continuous

snowstorm of choking dust. The dust was really pumice, and unlike snow, it was not going to melt

and go away, in warm weather or at any other time – it just accumulated, and quickly. Roofs began

to collapse under the weight, and Pompeii was being buried. This layer of pumice would eventually

exceed ten feet in thickness. Most Pompeiians took the hint, scraped together some belongings and

began to leave the city. But for reasons of their own, there were some who did not leave.

A pyroclastic flow can occur when the pressure of an eruption abates somewhat, and the

superheated, poisonous gases coming from the volcano can no longer be blown very far upward. This

leads to great clouds of volcanic material travelling rapidly down the sides of the volcano

instead of up into the sky. These flows can move very fast (up to hundreds of kilometers per hour,

depending on the slope) and can travel for several miles, and are instantly fatal to anything that

breathes. Early on August 25, after about 18 hours of dustfall, pyroclastic flows started making

their way toward Pompeii. The early flows struck the north wall of the city and were pretty well

stopped. But as they spent their energy, they dropped the debris they were carrying at the base of

the wall. This had the effect of contributing material to a "ramp" which was eventually high

enough to lift a flow over the wall and into the city. The first such flow was enough to ensure

that anyone still in the city would not be leaving. But there were more. And other volcanic

deposits continued for a considerable period.

After all the commotion was over, the now-lifeless city of Pompeii found itself buried under 30

feet of volcanic deposits and mudflows. Evidence has been found of nearly 2000 people who lost

their lives in the city. Many more undoubtedly perished outside the city, trying to escape, but

this number is unknown, and estimates vary widely. The shoreline which had bordered the city was

now a considerable distance away, thanks to all the deposits. Mt. Vesuvius had lost about 2000

feet of its elevation, probably because of the collapse of the peak into the now-empty magma

chamber beneath it. The Romans showed no interest in unearthing or rebuilding the city.

Centuries passed, and knowledge of and interest in the city faded to almost nothing. Until much

later, in the 18th Century, when accidental discoveries led to a painstaking excavation that

extended well into the 19th Century.

Early in the 21st Century, we were walking around the central train station in Naples, trying

to figure out how to get to Pompeii and into the excavated area for the fewest Euros. And we

found it when we located the booth that sells the Campania ArteCard. There are different flavors

of this wonderful discount card, and we settled on the Tutta la Regione version, which is

somewhat expensive at 27 Euros, but includes three days of all public transportation throughout

the area (as far south as Pompeii), admission to any two points of interest on a long list

(including both Pompeii and Herculaneum, normally more than ten Euros each), and 50% off on

admission to anything else on the list. We bought four, but unfortunately they didn't take

credit cards. We paid cash, which instantly wiped out most of the cash we'd just withdrawn from

the elusive ATM near our hotel, and we were immediately on the lookout for another ATM. Again,

we didn't find one at the train station, but we found our train by following signs to the

Circumvesuviana (this is the name of the train that follows the shoreline of the Bay of

Naples to the southeast, toward Pompeii). We boarded the train headed toward Sorrento (the end

of the line toward the south).

Circumvesuviana Sign

Pompei Scavi Station

Pompeii is more than 20 miles from Naples, and a traveler must pay attention to the stops

so as not to miss the one for Pompeii. This stop is called "Pompei Scavi" (the Italian

spelling for Pompeii only uses one "i"; scavi is Italian for "diggings" or

"excavation", and can also be found on signs at road construction sites). On exiting the

train station, one turns right to go toward the entrance to the ruins. On the way are a

number of places selling food and souvenirs, and across the street from these is the

Porta Marina entrance (and, thankfully, an ATM). Despite having ArteCards, we

still had to stand in the short line for the ticket office, where we showed the ArteCards

and were given Pompeii admission tickets. A short way downhill from the ticket office we

found turnstiles, where we used our tickets to enter the city.

Porta Marina Entrance

Porta Marina Area

Strictly speaking, we weren't quite in the city just yet, as we were still outside the Porta

Marina (or Sea Gate) to Pompeii. 2000 years earlier we'd have been standing in the Bay of

Naples, but in 2009, a mile away from the bay, we were looking at a walkway heading uphill

toward a well-preserved tunnel through a well-preserved city wall. We took some touristy

pictures and entered the city.

Outside the City Wall

Climbing the Hill

Approaching the Gate

Entering the Gate

When visiting the city of Pompeii, it is best to have a plan of what there is to see and

which of those things you're most interested in seeing. It's a very large place (once a city of

20,000, after all), and though there are a number of places that are roped off or behind

fences, for the most part you can go where you please. This being the case, it's very easy to

use up your time and energy wandering aimlessly and missing major points of interest. We

started out with the intention of following this advice – we'd downloaded a walking tour from

the Rick Steves web site, and began by following it carefully. But we lacked a couple of things

which we found to be important: one was a map, as we'd forgotten to pick one up on the way in,

and the other was the self-discipline to stick with the plan for more than ten minutes. Nella

eventually went back and found a map, but we never were able to locate the self-discipline.

Unfortunately, in Pompeii you're constantly surrounded by interesting things, and the urge to

explore them can be irresistible, especially if you're young and adventurous, like Philip and

Connie (or at least they were until the jet lag asserted itself). So we ended up missing some

of the major sights (the House of the Faun, the Amphitheater, the Gladiator School, the

brothels, etc.). But that being said, we did see a lot of cool stuff, as shown in the

following pictures. Starting with what was left of the Temple of Apollo, a short distance

past the city gate.

The Temple of Apollo

Colonnade and Statue of Apollo

Continuing down the path, we soon reached the city's Forum area, a large open area that

was once the center of the city. Adjoining the Forum there was a structure used for storage

of artifacts (mostly pottery). Also in this structure there were figures appearing to be

sculptures of eruption victims. But these weren't sculptures – they were formed by pouring

plaster into the cavities in the earth left after the bodies of eruption victims decomposed

over the centuries. They can be both fascinating and disturbing.

Nella and Forum Area

The Temple of Jupiter

Forum and Storage Area

Eruption Victim

Continuing Northward from the Forum, just across from the ruins of the Temple of Fortuna

Augusta, we found a mostly-intact building that we could enter, which once held the Forum

Baths.

Calidarium, the Forum Baths

Tepidarium, the Forum Baths

The Forum Baths

The Temple of Fortuna Augusta

Northward past the area of the Baths, we entered into residential Pompeii. Some houses

had obviously been large and luxurious, while others appeared to be working-class row

houses.

Via delle Terme

Columns, Casa di Pansa

Residential Area

Connie Crossing the Street

House of the Small Fountain

The Small Fountain

Torre di Mercurio, North Wall

The House of Apollo

Large Pool

After a while, the ruins started looking the same to us, so we retreated to the Forum

to plan out what to do next.

The Forum Area

The Forum Area

After looking at our map, we decided we'd visit the Villa of the Mysteries, on the

outskirts of town to the northwest. This involved a walk down a street with many funerary

monuments, called the Via dei Sepolcri. We found the Villa to be a large house in

pretty good condition, but we were never very clear on exactly what the mysteries were.

It seemed to have something to do with some well-preserved frescoes which appeared to

depict religious or cultish rites. Anyway, the whole thing was pretty mysterious to us.

Via dei Sepolcri

Massive Tomb

Mt. Vesuvius

In the Villa of the Mysteries

Connie and Bob with Tree, Villa of the Mysteries

Fresco, Villa of the Mysteries

Tourist Tableau - Philip, Bob and Connie

By this time, we'd been walking around a lot and we were jetlagged and hungry and we were

about ready to leave. We made our way back up the Via dei Sepolcri to the Forum and through

a ruin called the Basilica to the exit, from which point we had a nice view of modern-day

Pompeii.

Approaching Herculaneum Gate

Forum Area and Mt. Vesuvius

Colonnade and Tour Group

Nella and Basilica

Modern Pompeii

After exiting the grounds, we crossed the street to get lunch at one of the arrayed eating

establishments. Most of us had pasta, but Philip introduced himself to a proper pizza

margherita, consisting of a thin crust, tomato sauce, mozzarella and basil, and nothing else.

Pizza margherita is one of the specialties of the Naples area and is considered patriotic,

as it features all three colors of the Italian flag. The Campania region produces the best

mozzarella in the world, and Philip was well pleased. Then we walked back to the train

station and caught the next train back to Naples.

Concessions Near Entrance

Nella and Giant Lemons

Philip's Pizza Margherita

The Sorrento Train

You might be thinking this was enough activity for one day, less than 24 hours after

crossing a continent and an ocean, and this thought had crossed our minds as well. But

we were determined to become acclimated, and were willing to kill ourselves in the

process, if necessary. So we decided to visit one more destination for the day, and

we were going to go large. We would next visit the National Archaeological Museum.