The problem is that the Alhambra is in the city of Granada, and the trip between Seville and Granada is three hours each way (I swear they looked pretty close together on my map of Europe). So six hours of your day will be devoted to staring at the Spanish countryside, doing crossword puzzles, sleeping, or doing whatever you do on a train. And that’s if your train isn’t delayed (as ours was – we spent a half hour in an immobile train at a small station in a small town for unknown reasons), and doesn’t include the time spent going between the train stations and the points of interest in the departure and arrival cities. For this reason we can’t help but recommend staying in Granada for one or two nights if you want to visit the Alhambra, or at least somewhere a lot closer than Seville. For an Alhambra visit there’s the additional pressure of having to hit a timeslot: When you make a reservation on their website (highly recommended in the busy tourist months), you need to specify a portion of the day (before or after 2 PM) and a half-hour time range for your entry to the Nasrid palaces. If you miss your half-hour, you will be denied entry to the palaces, a rule about which they are very strict. There are other things to see, but the Nasrid palaces are unquestionably the highlight.

So what’s a Nasrid palace, and why would you want to see it? For that matter, what’s this Alhambra thing, and is it worth all the trouble? You’ll have to answer that last bit for yourself (our answer would be an unqualified yes), but read on for answers to the rest.

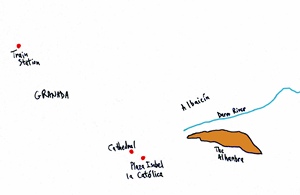

Granada Med Lrg |

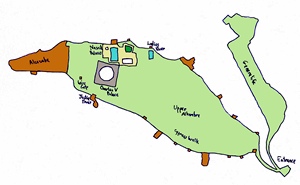

The Alhambra Med Lrg |

The Alhambra is a fortress/palace complex perched on a hill in Granada. It was originally built by the Moors in the 14th Century, after the reconquista had reduced their dominion to a small part of Spain centered on Granada. Prior to this time the hilltop had been used as a defensive fortification, with greater and lesser degrees of success, at times going back to the 9th Century. Around this time it acquired the Arabic name al-Qal’at al-Hamra, meaning “the red fortress”, referring to the red-colored clay prevalent on the hill. Late in the 13th Century plans were laid out for an extensive complex on the flat top of the hill. The existing fortifications at the west end (known as the Alcazaba) would be augmented, and an area east of the fortifications was reserved for palaces. Since the rulers of Granada at the time were members of the Nasrid dynasty, these have come to be known as the Nasrid Palaces. They were built in the 14th Century under multiple rulers, and as the original plan was short on details, the placement of the palaces developed in what appears to be a haphazard manner, dependent on the tastes of the individual rulers. But the palaces were connected to each other, and each featured a central courtyard surrounded by rooms, extensively decorated. They were all dedicated to a theme of “paradise on earth”. The Nasrid rulers were only able to enjoy their palaces until 1492, however, as a resurgent reconquista under Ferdinand and Isabella confronted King Boabdil with overwhelming force at this time and demanded that they leave Spain, along with their followers (the alternative no doubt being annihilation). It is said that Boabdil wept as he departed and was comforted by his mother, who said, “Don’t cry as a child over what you could not defend as a man”. Harsh.

Over the ensuing centuries the complex suffered from abuse and neglect, and fell into a general state of disrepair. After some towers were destroyed during the French occupation in 1812 and further damage was caused by an earthquake in 1821, a restoration project was begun in 1828. The Alhambra’s cause was greatly helped with the publication of a book called Tales of the Alhambra by the American author Washington Irving, who visited and stayed in the fortress in 1829. The book, published in 1832, consisted of a series of essays and short fiction, and brought the Alhambra and its plight to the attention of the reading public in Europe and America. This added impetus to the restoration effort, which (as we were to discover) continues to the present day.

Our train ride to Granada was pleasant enough, considering. The landscape is attractive and dotted with the occasional wind farm. Apparently Spain is the world’s number one producer of olive oil, so there were lots and lots of olive trees.

Sunflowers and Hills Med Lrg Xlg |

Town with Hill Med Lrg Xlg |

Eventually we left the train at the Granada train station, which isn’t very close to the Alhambra. There are three main choices at this point: one can take the long walk (slowest but cheapest), take a taxi (fastest but most expensive) or take the bus. We opted for the bus. There is a bus stop just up the hill from the train station, on Constitución. Any bus numbered from 3 to 9 stops at the Cathedral, which is easy to recognize. The square next to the Cathedral is the Plaza Isabel la Católica, and minibuses with the number 32 leave from this square to climb the hill to the Alhambra (a normal-sized bus would probably have trouble with the switchbacks). After some initial confusion we found the minibus stop and rode the next bus to the top of the hill, where we were dropped off by the ticket office at the east end of the Alhambra complex.

If you arrive at the Alhambra without a reservation, you will need to wait in line to buy a ticket. If they are sold out (as they often are during the busy tourist season), you will have to leave and come back another time. If you have a reservation, you will need to print out your tickets at a ServiCaixa terminal, using the same credit card you bought the tickets with online. ServiCaixa terminals are scattered around Spain, but just in case there are some off to the right from the ticket line. We were a little nervous about how well this would work with American credit cards, but as it turned out we didn’t have any problems.

And despite our delayed train and our bus confusion, we were also right on time – our Nasrid Palaces reservation was for 12:30, it was recommended to arrive an hour earlier, and it was almost exactly 11:30. As if we’d planned it. We passed through the gate and almost immediately saw a sign pointing right to the Generalife. The Generalife is a palace separate from the other palaces which apparently has especially beautiful gardens. I say “apparently” because we didn’t go that way, resolving to return if we had time following our appointment with the Nasrid Palaces, and as it turned out we didn’t. Instead we went straight, passing through some nicely maintained gardens along what is called the Cypress Walk.

Secano Garden and Friary MP4-Sml MP4-Med WMV-HD |

Pink Flower Med Lrg |

Off to the right were some small buildings and a former friary which is now a hotel, and eventually we passed through a gate, giving us the uncomfortable feeling that maybe we’d just left the grounds without actually seeing anything. But things were fine after all, and we continued past some buildings, including a church on the right, eventually coming to a big gray bunker of a building on the right, known as the Palace of Charles V.

Just ahead was an archway called the Wine Gate, and if you turn right after the Palace but before the Gate, you will reach the gathering place for people with Nasrid Palace reservations. But we had more than a half hour to kill, so we continued through the Gate to the Alcazaba.

As mentioned above, the Alcazaba is the main defensive portion of the complex (and the oldest), and as of now it consists of several towers (with names) and walls between them. Inside the walls is an area called the Plaza de las Armas in which can be seen concrete outlines representing structures that once stood here.

Nella and Alcazaba MP4-Sml MP4-Med WMV-HD |

The Keep, Cracked Tower and Alcazaba Fortification Med Lrg Xlg |

In keeping with its function as a defensive fortress, fine views of the surrounding area are to be had from the walls and towers of the Alcazaba. The views these days are mainly of the city of Granada, and the invading armies come armed with digital cameras.

The Keep and the Arab City Wall Med Lrg Xlg |

Nella, Albaicín Area and St. Nicholas Church MP4-Sml MP4-Med WMV-HD |

The view is particularly good from a tower called the Watchtower, which also has flags and a bell. The bell is used to sound the alarm when necessary. This was impossible for awhile after 1882, when the bell was struck by lightning. Its replacement appears to have a lightning rod.

The Keep, Bob and Watch Tower MP4-Sml MP4-Med WMV-HD |

Watch Tower (Torre de la Vela) Med Lrg Xlg |

Granada and Cathedral from Watch Tower MP4-Sml MP4-Med WMV-HD |

Bell on Watch Tower Med Lrg Xlg |

After a few minutes spent crawling around on walls and towers (well, Nella wasn’t really interested in much of this, but at least she got some reading done) the time for our Palace appointment was drawing near, so we headed for the Alcazaba exit by way of a garden along the outside of the south wall.

Palace of Charles V and Nasrid Palaces MP4-Sml MP4-Med WMV-HD |

Nasrid Palace (Palacio Nazaríes) Med Lrg Xlg |