The Vasa (sometimes called Wasa) was a Swedish warship, built between 1626 and 1628

to be the most powerful warship in the Baltic Sea. Sweden, under King Gustavus Adolphus (sometimes

called Gustav II Adolph), was in the midst of three separate conflicts, with Russia, Denmark and

Poland/Lithuania (most actively with the last of these), and demanded a navy that could soundly

defeat any of these enemies.

Gustavus Adolphus

The Vasa was state-of-the-art for its time. It was 226 feet long, 38 feet wide and 172

feet tall, with a draft of 16 feet. It was built to carry 64 guns, including 48 that could fire

24-pound shot, and 300 soldiers in addition to its crew of 145 sailors. It was designed to push

the envelope as far as speed, maneuverability and firepower. Unfortunately, the state of the art

in 1626 wasn’t what it might have been, and this became unmistakably obvious on its maiden voyage,

on August 10, 1628.

Stockholm Harbor

On this occasion the Vasa began from its mooring, near the Tre Kronor Palace on

Gamla Stan (a site now occupied by the Royal Palace), and was warped southward (pulled by an

anchor line, necessary because of the wind coming from the south). On reaching the larger

island of Södermalm, the ship set its sails and turned to the east. On reaching a point where

the sails could catch the full breeze between the bluffs of Södermalm, the ship leaned heavily

to port (the left). The lower row of gunports on that side of the ship, which had been opened

to fire a salute, suddenly found itself below the waterline, and water rushed into the gundeck.

The gunports were ordered closed, but it was too late. The ship was unable to right itself,

and within minutes it had sunk to the bottom of the harbor, in 105 feet of water. Much of the

crew was rescued by the small private boats which had gathered to celebrate the occasion (some

crew members clung to the Vasa’s masts, which were still above the water), or were able to swim

to shore, but 30 crew members were lost (mainly sailors trapped on the lower decks). The full

distance of the Vasa’s first and only voyage was 1,400 yards.

Horrified Spectators

At this point, you might be asking yourself why there’s an entire museum devoted to this ship.

After all, there have been a great number of wars over the centuries, in which thousands of

ships have been lost, in a plethora of scenarios. What’s so special about this one? And not

only is there an entire Vasa Museum, this museum

is the most-visited museum of any kind in all of Scandinavia. Is this some kind of weird

Scandinavian affinity for incidents of extreme haplessness?

The Vasa Museum

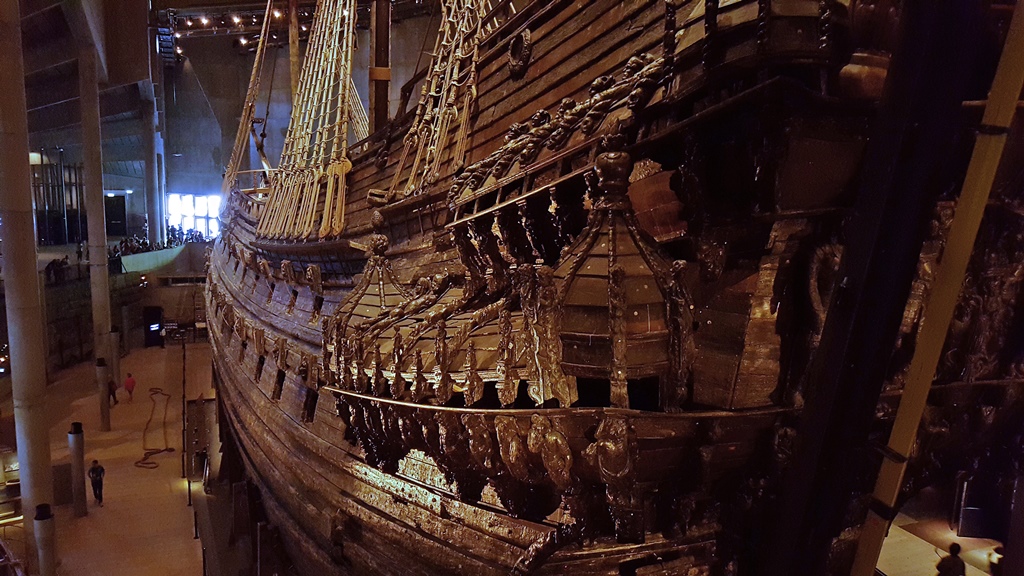

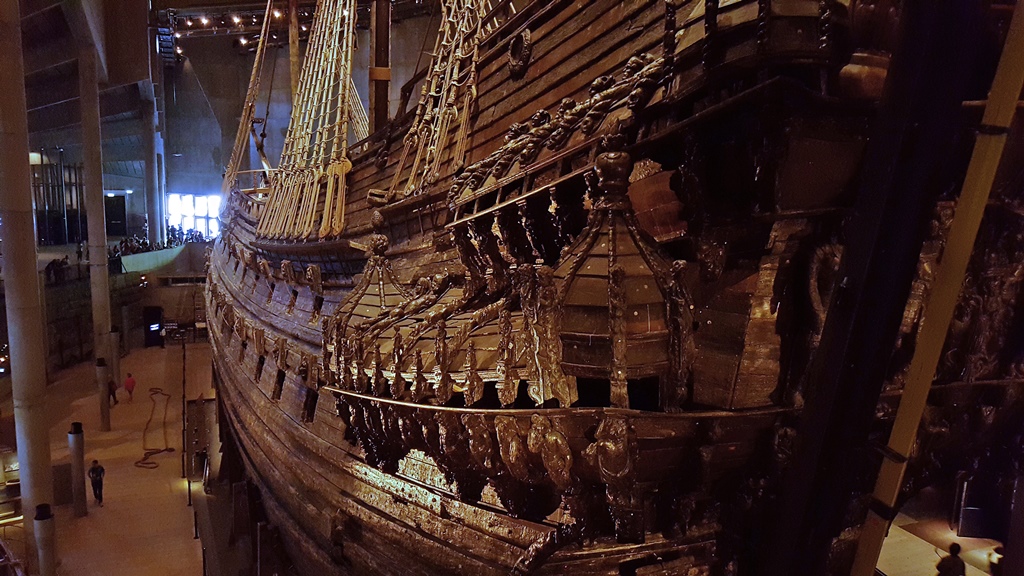

The answer is the presence of the Vasa itself, which is front and center in all its

glory, after having spent more than 300 years at the bottom of Stockholm’s harbor. In the late

1950’s, long after the ship had been largely forgotten, its location was rediscovered by an

amateur archaeologist, and an immense amount of effort, money, bravery and science were thrown

at the ship to fish it out of the harbor, make it float again, restore it to something approaching

its original condition and treat it to keep it from falling apart in place. The result is the

best-preserved 17th Century ship in the world.

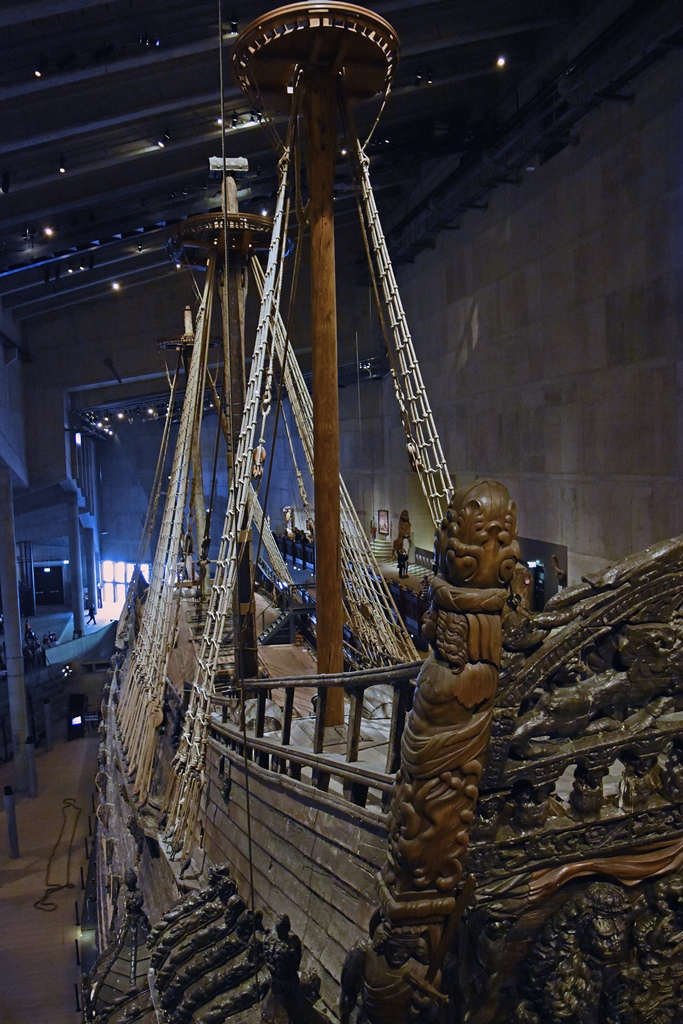

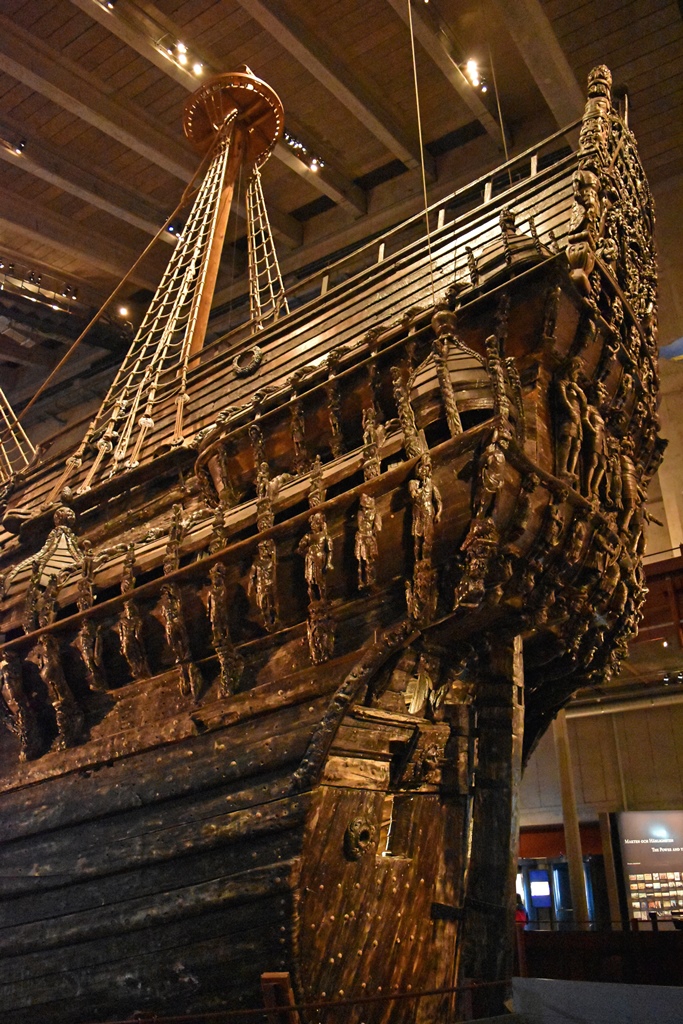

The Vasa, from Port Bow

You might be feeling like there are some interesting stories related to all of this. There

are certainly some stories – you'll have to judge for yourself about the “interesting” part.

We’ll start with the inquest. In the days following the sinking, people were shocked, angry,

depressed and scared. A message was immediately sent to the king, who was in Poland, and by

the time the response came back (basically “Find out whose fault this was and punish them!”),

the inquest was already well underway, with the same goals. One thing that was obvious to

everyone was that the ship had been top-heavy, judging from the amount of tippage in response

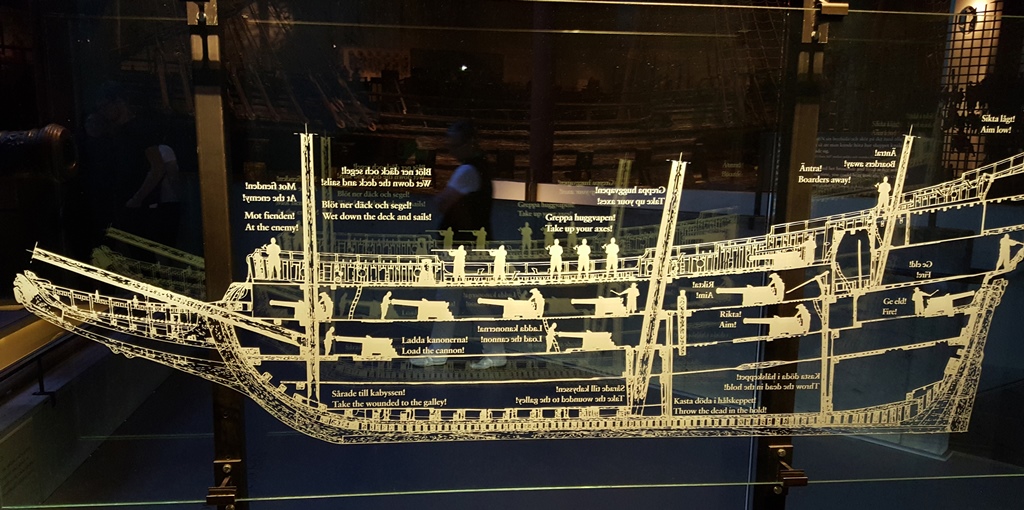

to a moderate breeze. Here are some views of the Vasa’s decks:

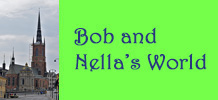

Vasa Cross-Section

Diagram of Decks

Model of Vasa Decks in Use

Gun Deck (Recreated)

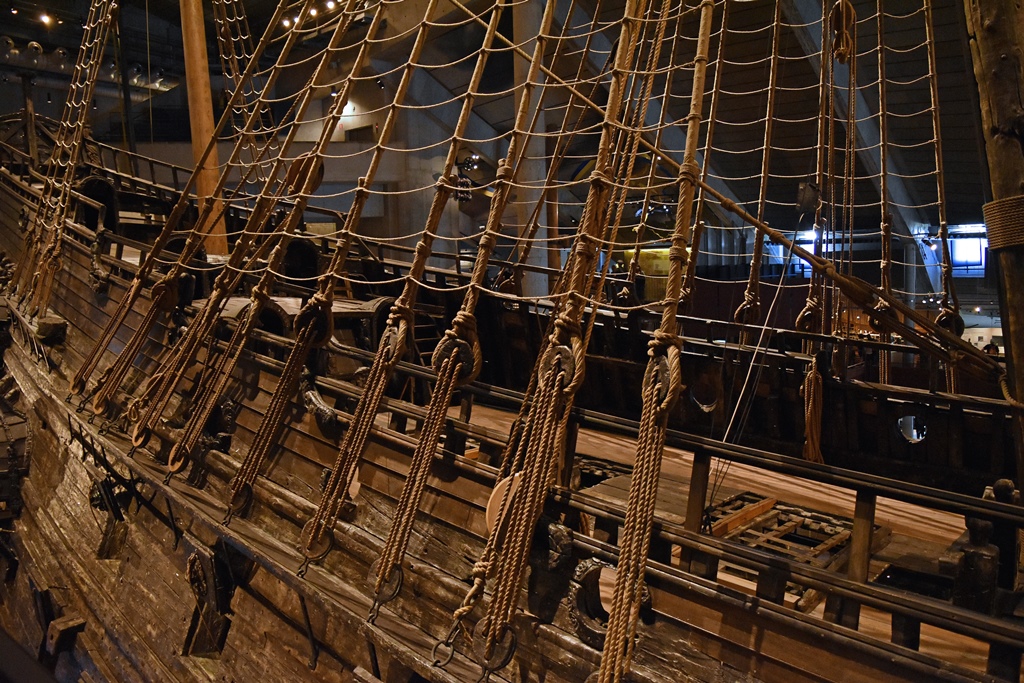

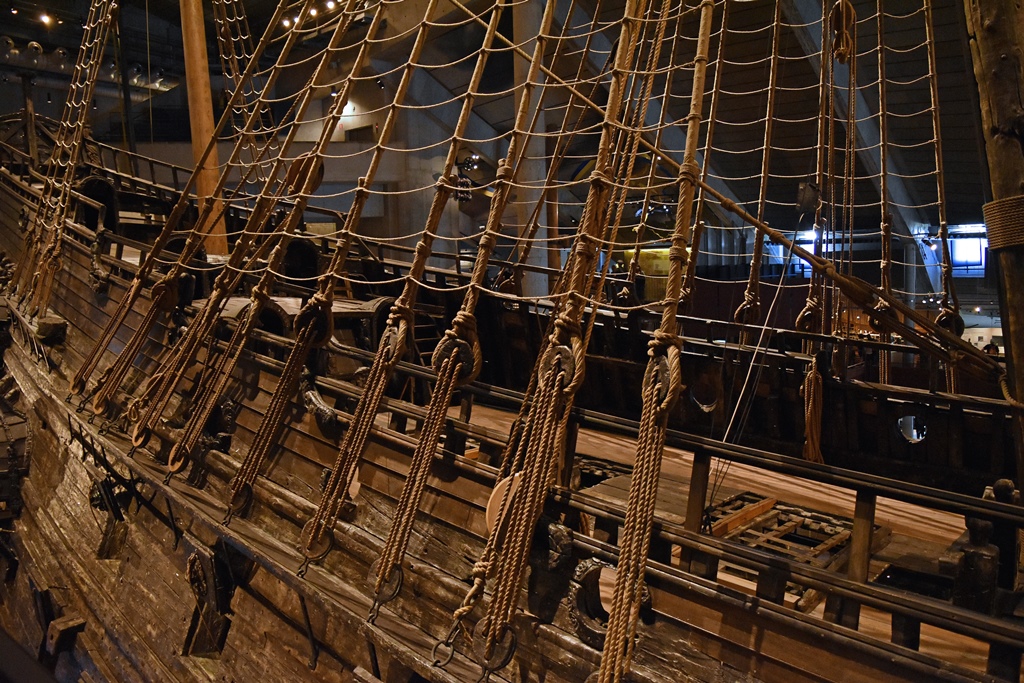

Below the top deck, there are two gun decks (each with several cannons), a deck called the

orlop (used for storage of cordage and spare parts, among other things) and the hold

(used for food and water storage, mainly in barrels, plus the ship’s ammunition and powder

magazine). Below the hold is a slim level filled with rocks. This is ballast, used to lower

the ship’s center of gravity. The Vasa had 120 tons of ballast stone, which might have

been enough for a different ship. But the Vasa’s other decks had more headroom than most

ships – a luxury for the crew, but not good for keeping the center of gravity low. The upper

gun decks were filled with cannons which were larger (and heavier) than usual, to supply

overwhelming firepower. Also, the Vasa had an extremely high sterncastle, a deck at the

ship’s stern that could be used as a firing platform toward enemy ships, or onto the Vasa’s own

deck in case of boarding by enemy combatants. Besides making the center of gravity lower, another

measure that could have been taken in the ship’s design to improve its stability might have been to

make the ship wider. This however, might have had a negative effect on the ship’s speed.

When it came down to it, the principal design decisions of the Vasa were made by two people.

One was the shipwright of the Stockholm shipyard, the Dutch-born Henrik Hybertsson, who would

have to be considered the main designer. Hybertsson had a considerable amount of experience in

shipbuilding, unlike his co-designer, who had several ideas for making the ship a powerful

weapon, many of which had not been tried before. Hybertsson undoubtedly had misgivings about

some of these ideas, but unfortunately his co-designer was King Gustavus Adolphus himself, who

could not be denied. It’s impossible to say what the final product would have been like if

Hybertsson had stayed on the project, but unfortunately he died in 1627, part way through the

ship’s construction. His replacement on the project was even less likely to get into design

arguments with the king, but it was clear that he and many others at the shipyard had grave

concerns over the ship’s stability. At one point they demonstrated this instability to a Vice

Admiral, who ordered the demonstration halted when he became afraid that the unfinished ship

would capsize. The king was informed, but he was off fighting in Poland at the time, and the

only communications they received from him in response were expressions of impatience with the

construction. So the ship was finished and put to sea as soon as possible, and was soon under

the sea. The resulting inquest couldn’t lay fault for the disaster at the feet of Hybertsson,

as he was dead before the project was finished. So the fault was assigned to the only place it

could be assigned: to … nobody. It was just one of those things.

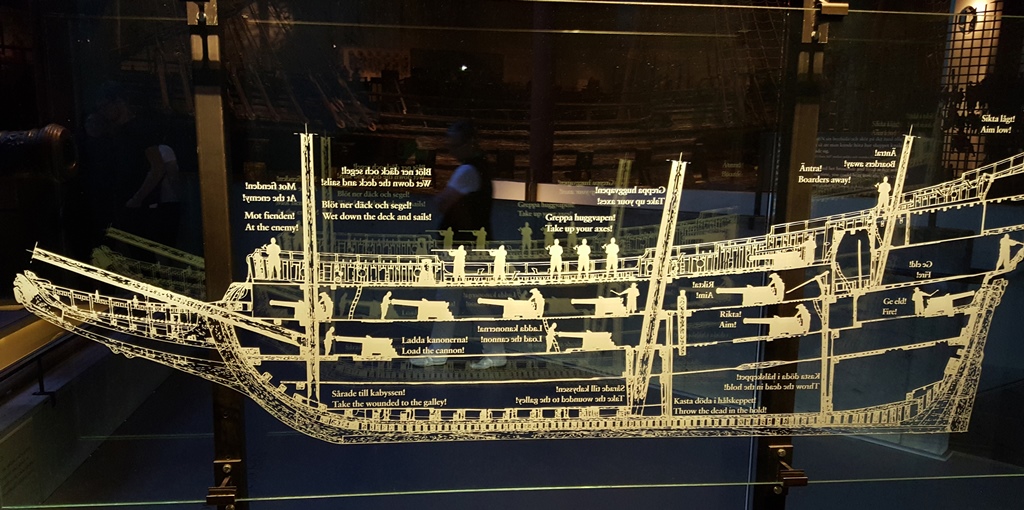

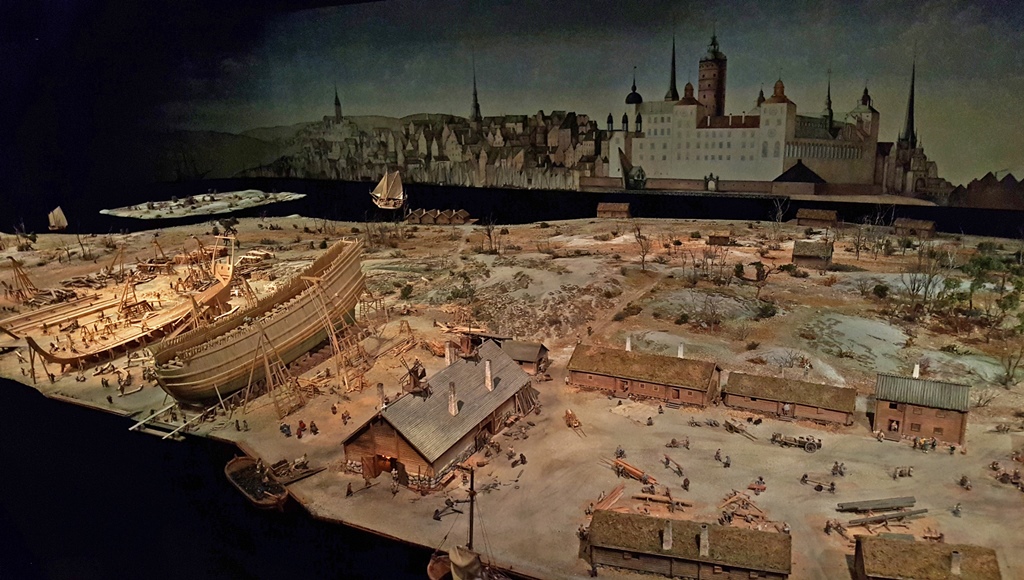

Shipyard Diorama

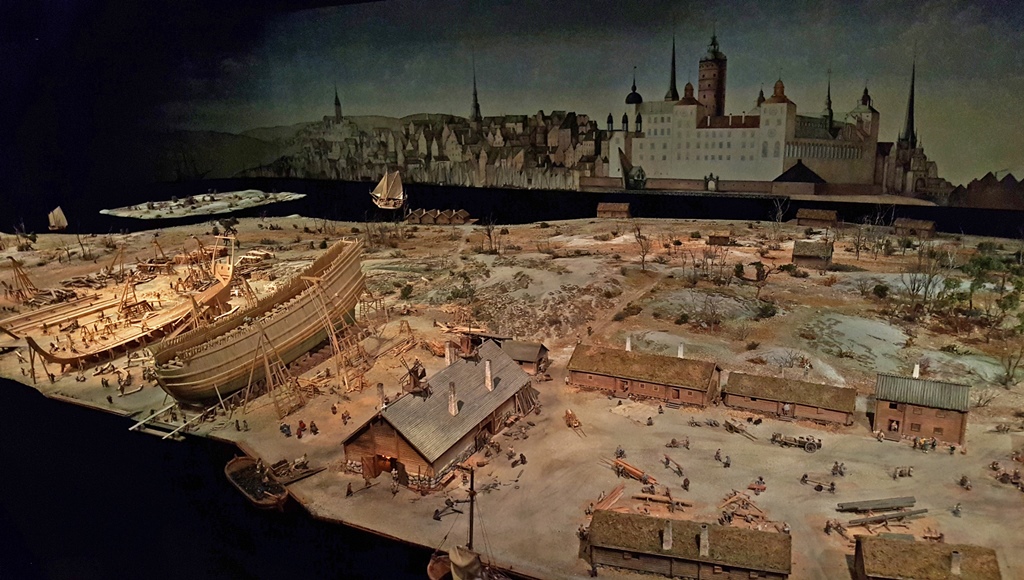

Almost immediately, attempts were made to raise the ship. This was done by lowering several

lines with anchors on them in an attempt to snag the ship. The lines were attached to empty

boats which were filled with water, nearly to the point of sinking. The lines were then

tightened, and the water pumped out of the boats. The idea was that the boats would rise,

and lift the sunken ship as they did so. A clever idea, but the ship was well stuck in the

mud at the bottom of the harbor, and wouldn’t budge. The main effect was to tear pieces off

of the sunken ship. The tactic was soon abandoned.

First Salvage Attempt

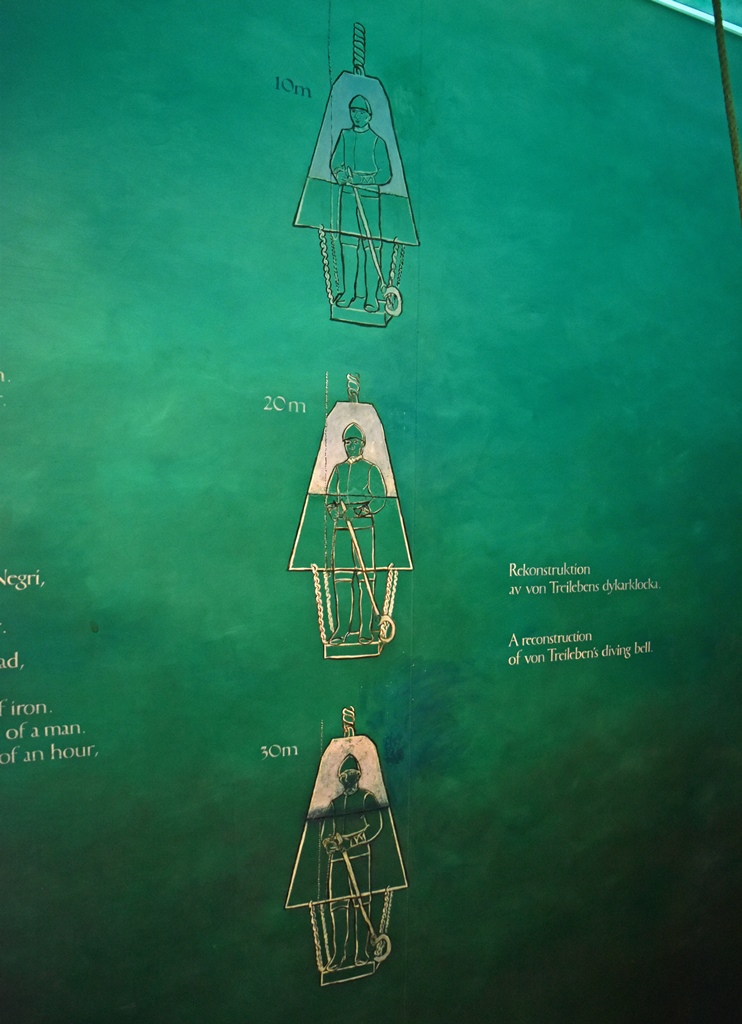

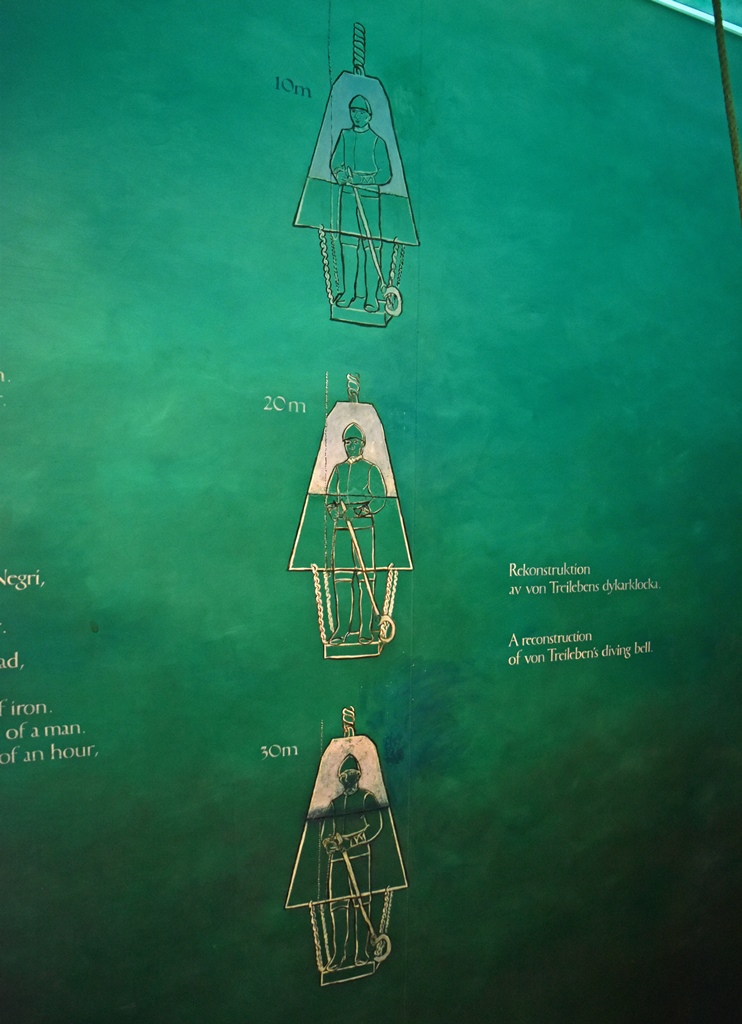

35 years after the sinking, an attempt was made to salvage the ship’s cannons. They wouldn’t

have been usable as cannons anymore, but they were made of bronze, and bronze could be melted

down and reused, and was therefore valuable. A Swede named Albrecht von Treileben used a

diving bell to retrieve more than 50 of the guns, the most successful diving bell assisted

salvage operation performed to date. The diving bell was actually more or less bell-shaped,

and had a lead plate suspended below it, which kept the bell from turning over, and also gave

a diver something to stand on. The diver was equipped with a long tool with a hook on its end.

It was necessary to tear through the upper deck to get to the guns, and as they were found

divers attached lines to them which were used to pull them up. Divers could only stay down

about 15 minutes per dive, due to the cold water.

Diving Bell

Diving Bell in Use

At the time of the Vasa’s rediscovery in 1956, by an amateur archaeologist named Anders

Franzén, the ship in many ways was in excellent condition for a 300-year-old wreck. There were

a few reasons for this. First, because of the harbor’s location near the outflow of Lake

Mälaren, the harbor’s water is almost more fresh water than salt water, making for an unsuitable

environment for certain sea creatures (particularly shipworm, which is actually a type of clam)

that normally feast on wooden shipwrecks. Second, the harbor water was polluted for centuries

because of the large populace and the amount of industry in its vicinity, and this also kept

sea creatures away. And third, parts of the ship and many of its decorations became buried in

the mud at the bottom of the harbor, and were thus protected from erosion by particulate matter

suspended in the prevailing current. On the other hand, much of the ship was not buried, and

was thus subject to a certain amount of this erosion. And any fasteners made from iron (like

nails) rusted away within a few years after the wreck, and many affixed decorations (and some

of the ship’s structure) quickly became separated from the main body of the ship.

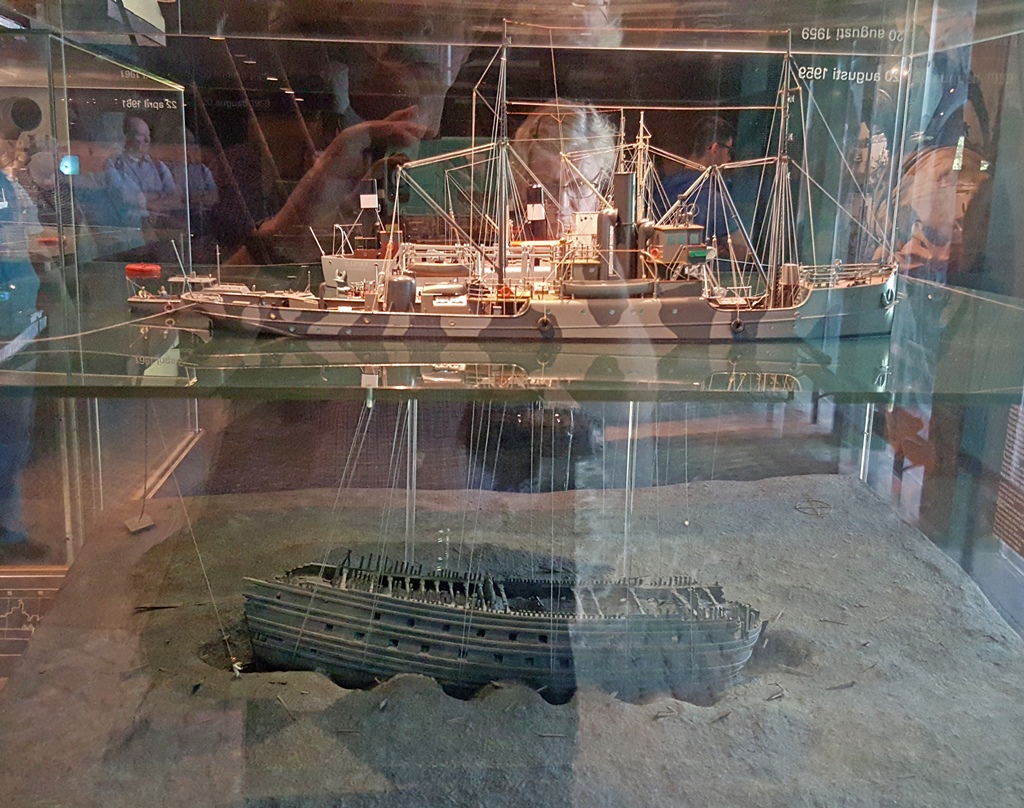

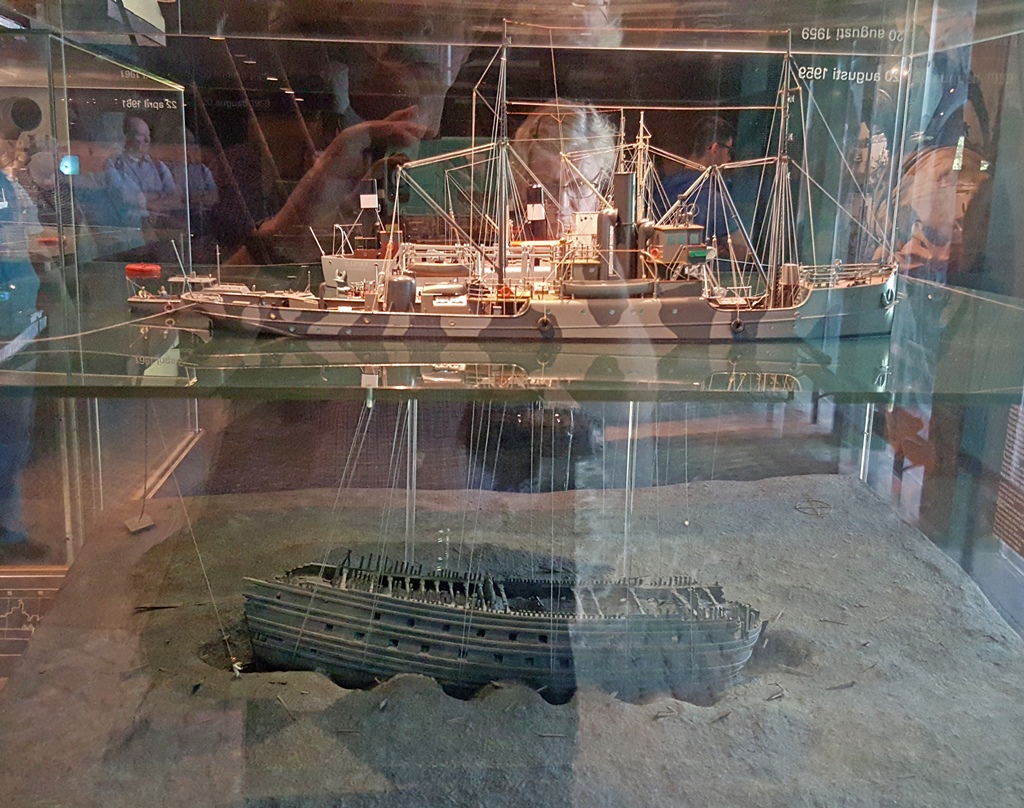

So how was this monster of a ship exhumed from its watery grave and brought back to the light

of day? Actually, the general idea wasn’t that different from what was tried immediately after

the sinking. Except for the part about blindly trying to snag parts of the ship from above.

In the 20th Century, there were divers and electric lights and high-pressure water jets for

digging, and all of these things were used to dig six tunnels underneath the wreck, through

which steel cable slings were threaded and attached to pontoon ships on the surface. This was

done very carefully, as the danger to both the ship and the divers was extreme – both the ship

and the tunnels were fragile and subject to collapse. This part of the operation took two

years by itself, and fortunately there were no serious accidents. Next, the ship was lifted

gradually, through the filling and pumping out of the pontoon boats while tightening the

cables.

Model of Salvage Operation

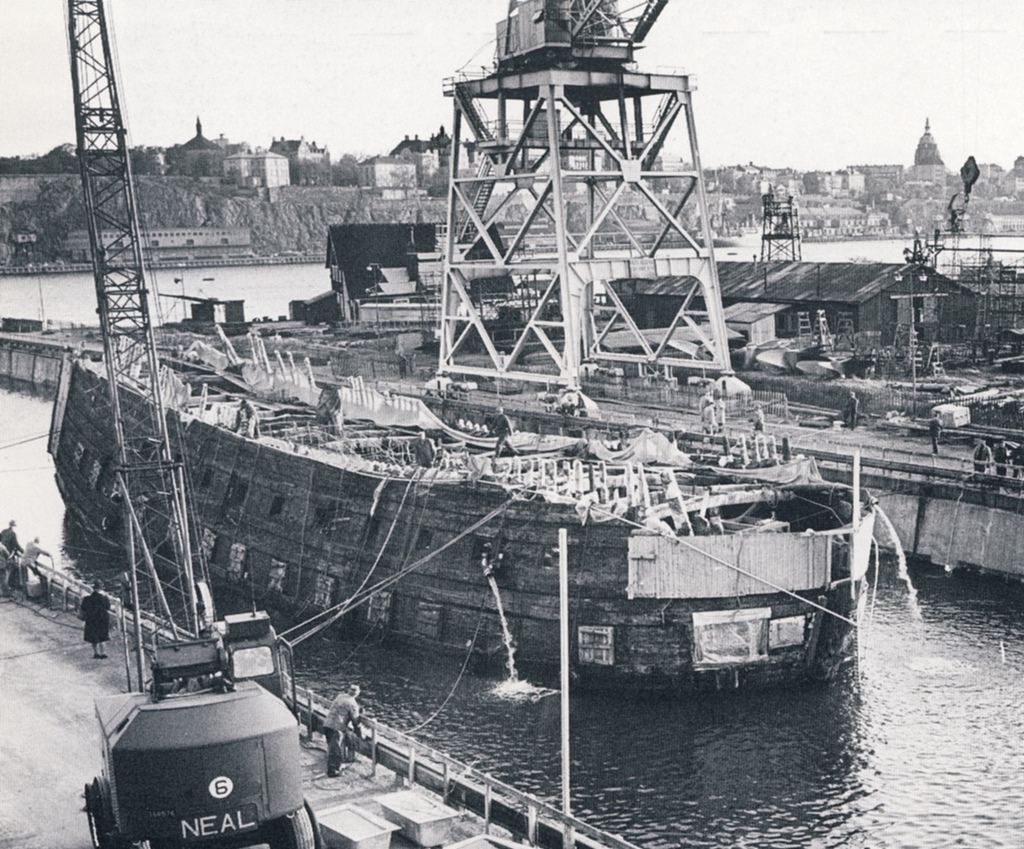

Once free of the mud, the ship was towed to a less vulnerable part of the harbor while still

underwater. Divers cleared remaining mud to reduce the weight and attached temporary lids

and temporarily plugged holes to make the hull mostly watertight (this part took a year and a

half), and the ship finally broke the surface in April of 1961.

Recovered Vasa, 1961

Once the Vasa was in a drydock, restoration work began. First, missing bits and

pieces had to be found. The original sinking site was combed for decorations and other

pieces that had fallen from the ship. Some bits were bigger than others – the entire

sterncastle had come loose, for example. In the end, the vast majority of the ship was

recovered, but there were parts that had to be recreated from new materials. A structure

was built around the ship so people could view it. Analysis of the wood in the ship

showed that there had been chemical reactions that contributed to the wood’s decay. It

was decided that the ship needed a bath. A nice, long bath. Like 17 years. Of

polyethylene glycol, to retard the chemical reactions, which had accelerated in the

presence of oxygen. Followed by a long period of drying, which is still in progress.

But it’s been determined that harmful reactions are still taking place (primarily

formation of acids which lead to a breakdown of the cellulose forming the wood).

Research is ongoing, but as of now, the clock is ticking. In the meantime, you can visit

the Vasa at the Vasa Museum, which was completed in 1990. It’s not possible to

actually board the ship, but it’s possible to view it from a variety of vantage points.

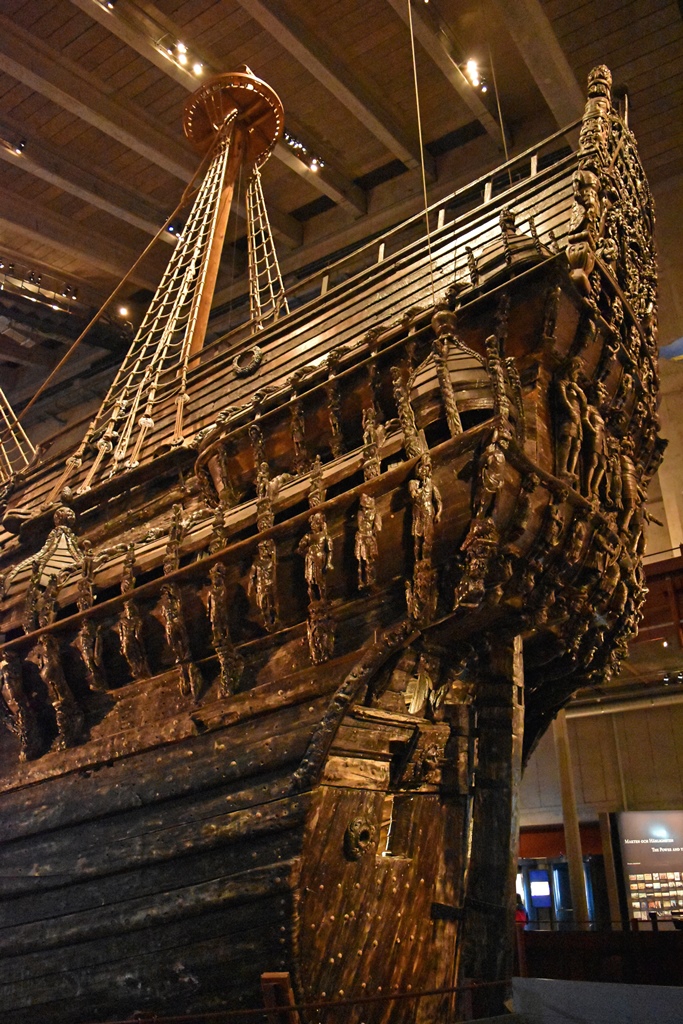

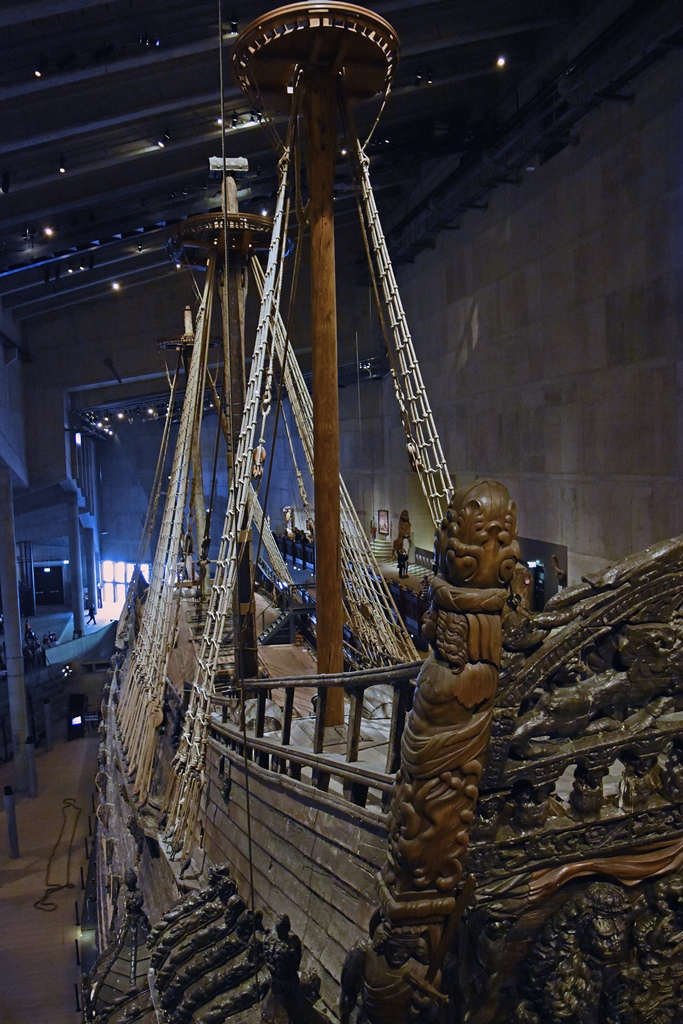

The Vasa, Beakhead

Vasa, Bowsprit and Beakhead

Vasa, Port Side Gunports

Vasa, Port Side

Vasa, Port Side

Vasa Sterncastle

Vasa, Upper Stern

Vasa, Lower Stern

Vasa Rudder

Vasa, Starboard Side

Vasa, Hull and Longboat (also recovered)

Under the Vasa

From the pictures, it should be obvious that the Vasa was intensely ornamented. The

ship is covered with little wooden sculptures, though many of them are at least somewhat

eroded. At least six sculptors (plus assistants and apprentices) are thought to have worked

on the Vasa, though none have been explicitly identified. The figures depict a variety

of subjects. There are biblical, historical, mythological and nationalistic sculptures.

Lions are a recurring motif. 20 figures lining the beakhead are thought to depict Roman

emperors. And the sculptors weren’t above a little propaganda. As the Vasa was being

built, Sweden’s principal adversary was Poland, and a figure near the front of the ship

depicts a Pole (identifiable from characteristic hairstyle, clothing and moustache) cowering

under a bench, apparently terrified at the sight of the mighty Swedes.

Vasa Beakhead, with Emperors

Humiliated Pole (reproduction)

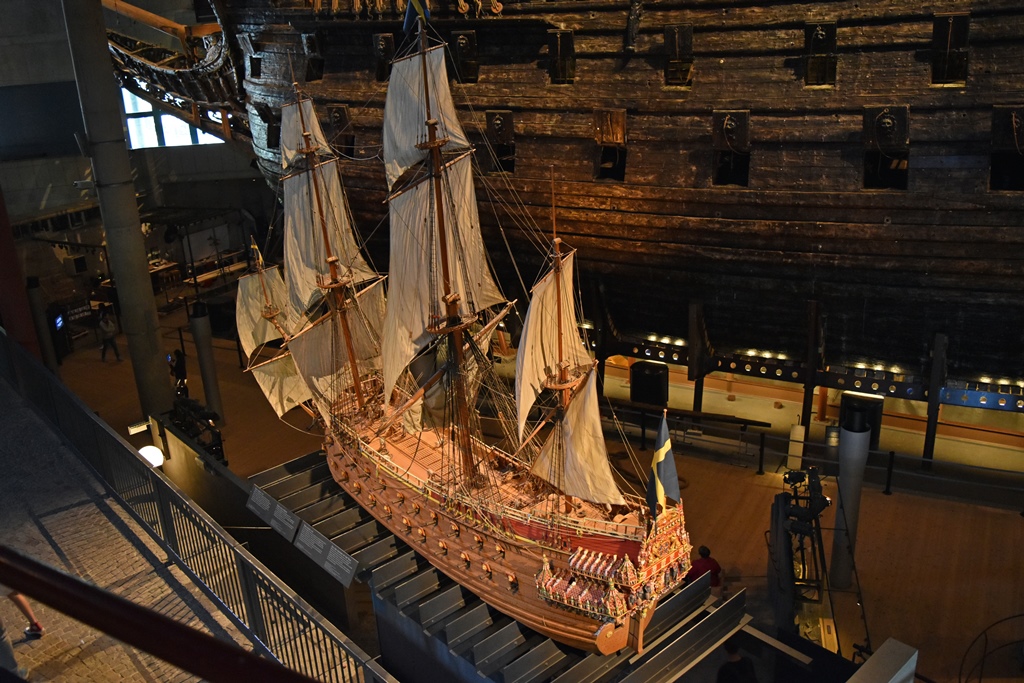

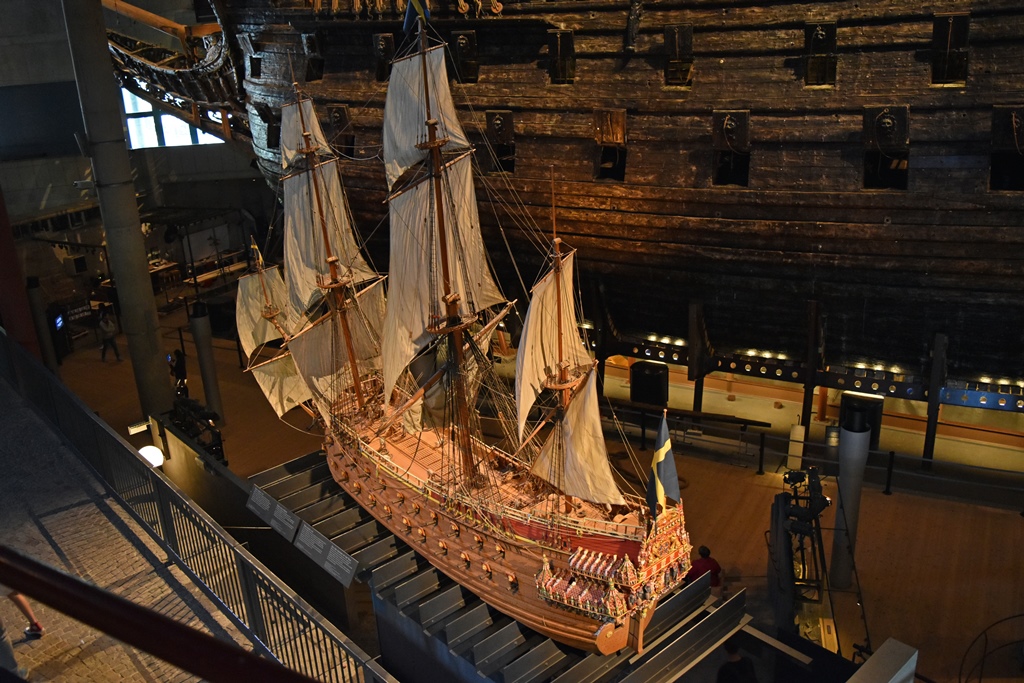

As it was making its way through the harbor back in 1628, the Vasa must have been an

inspiring sight. Not only were all of the little sculptures uneroded, but they were also gilded

and painted in vivid colors. Many of the sculptures recovered from the mud still had paint

residue on them. In the museum, there is an impressive scale model of the Vasa as it’s

thought to have looked back on that day.

Vasa Model Next to Vasa

Model of Vasa, Stern View

Model of Vasa, Gunports

Model of Vasa, Port Bow

Reproductions of Stern Figures

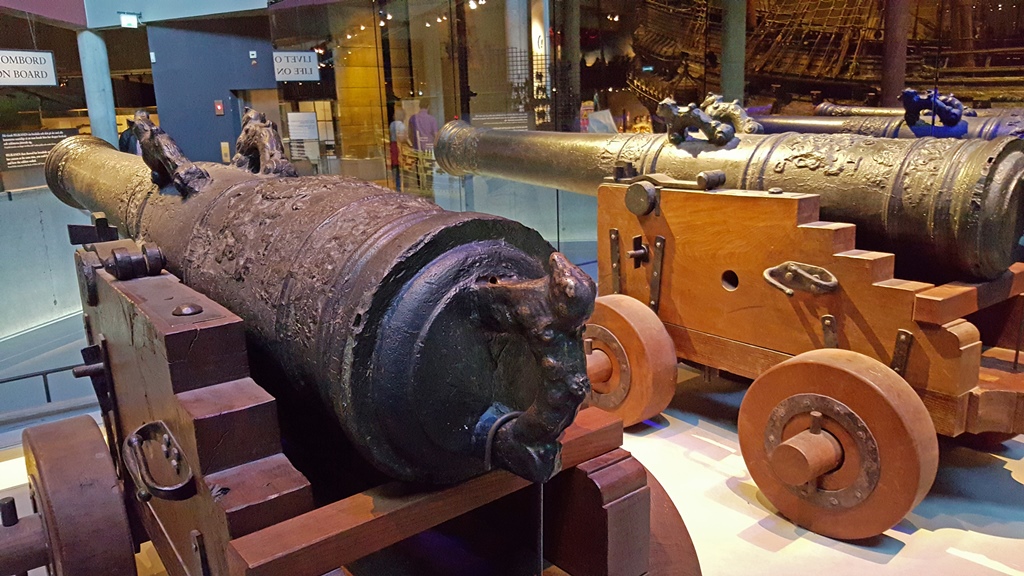

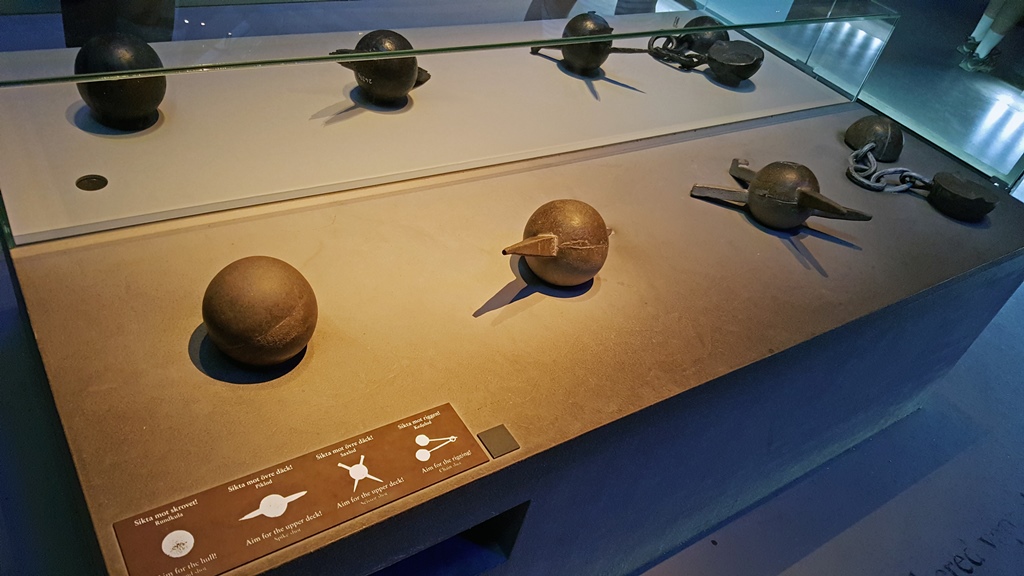

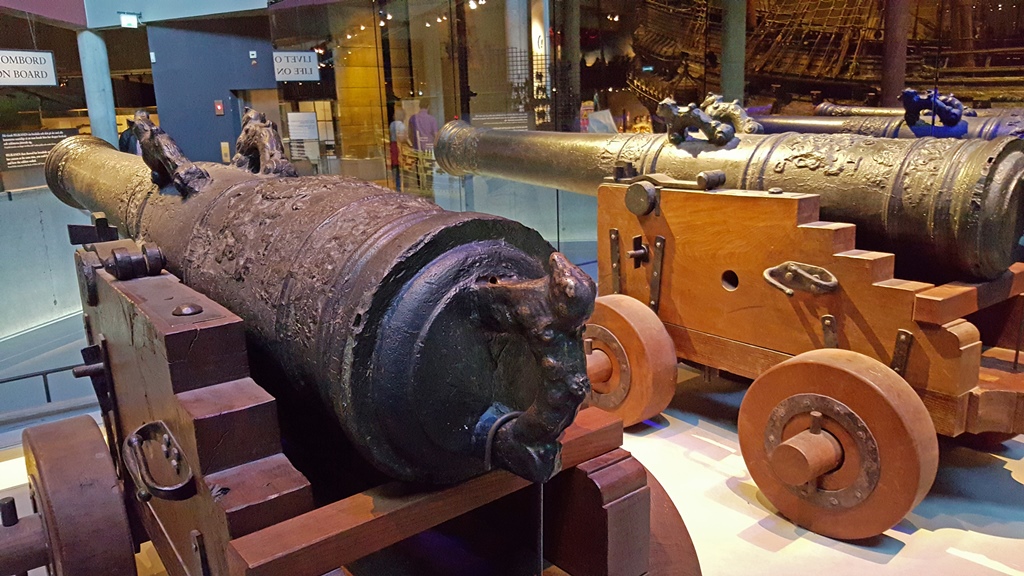

The museum has many exhibits related to the ship, some of which appear in photos above.

Here’s another, all about cannons.

Bob and Cannon

Cannon

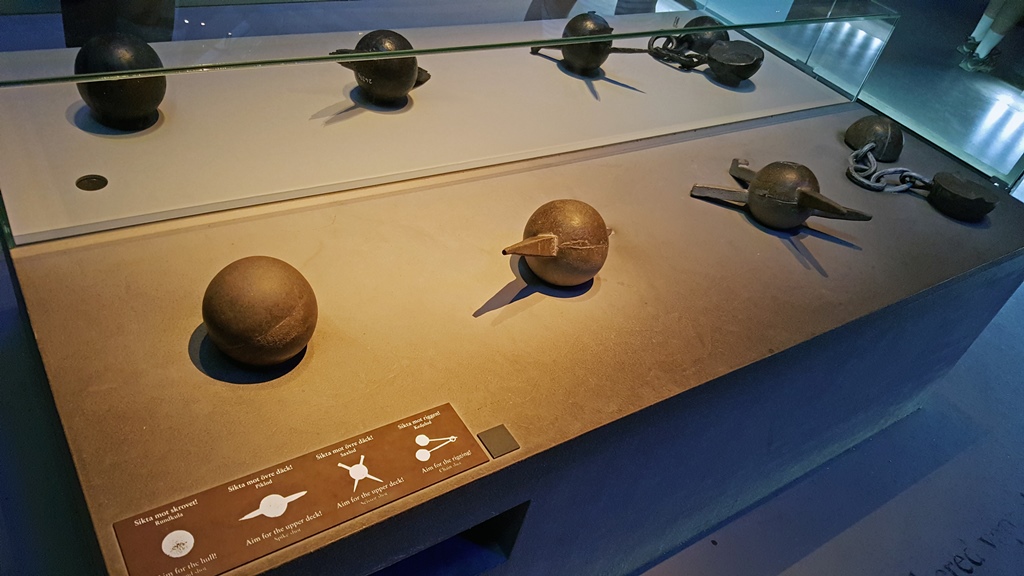

Types of Ammunition

Cannonball Damage

Having had our fill of the Vasa tragedy, we left the museum and headed for a more

peaceful one, the nearby Nordic Museum.