Stonehenge from Northeast

You've undoubtedly heard of Stonehenge – everyone's heard of Stonehenge. And

you probably know a few things about it. It's a group of big rocks somewhere

in England, arranged roughly in a circle, and put there a long time ago by people

unknown, for purposes unknown. And you may have heard some things about Druids

or space aliens having something to do with it. At one time this is mostly what

anyone knew about Stonehenge. But researchers have filled in some of the blanks,

and can make knowledgeable guesses about some of the others. As it turns out,

Druids did not build Stonehenge – they came way too late. It's hard to say

anything for sure about the space aliens – they've been very good about doing

weird stuff and disappearing without a trace. But while it's impossible to prove

that extraterrestrials had nothing to do with it, it is possible to prove that

they weren't necessary, at least from a physical standpoint. As far as the

purposes behind Stonehenge, there have been many theories and few satisfying

conclusions. Your guess might be as good as anybody's. Or maybe not.

Southern England

Stonehenge is located on the Salisbury Plain, named for the cathedral city of

Salisbury, 10 miles to the south. And no, Salisbury steak has nothing to do with

the city or the plain (it's named after a guy). Our drive across the plain from

Bath to Stonehenge took about an hour (the distance was about 35 miles). From

the bus our guide led us to a Visitor Centre, where we were given the necessary

credentials, audioguides, and about an hour and fifteen minutes to explore

Stonehenge and return to the bus. This wasn't as easy as it might seem, as

Stonehenge is just over a mile from the Visitor Centre. The round-trip walk,

plus an exploration of the site (while listening to the interesting discussions

from the audioguide), plus a look at some exhibits around the Visitor Centre

might have made things a little too close for comfort. Fortunately, there was a

shuttle bus from the Centre to the site.

Shuttle Bus

We boarded the next bus and soon found ourselves to the northwest of

Stonehenge, on a path that encircles the site. "Encircles" isn't quite the

right word, as the path is more of an irregular blob shape, mostly a respectful

distance from the stones, but at one point coming within maybe 20 feet or so.

At no point did the path pass among the stones – it was roped off from any

close approach. We elected to proceed in a clockwise direction. The weather

was cold and windy, which apparently isn't unusual.

Stonehenge from Northwest

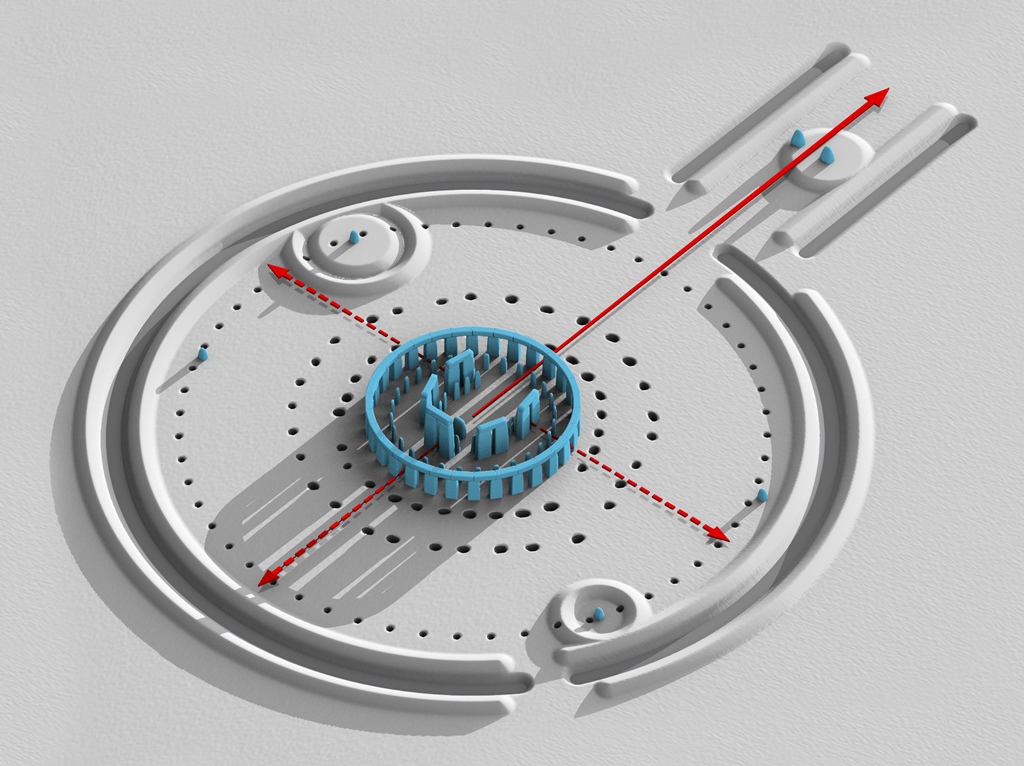

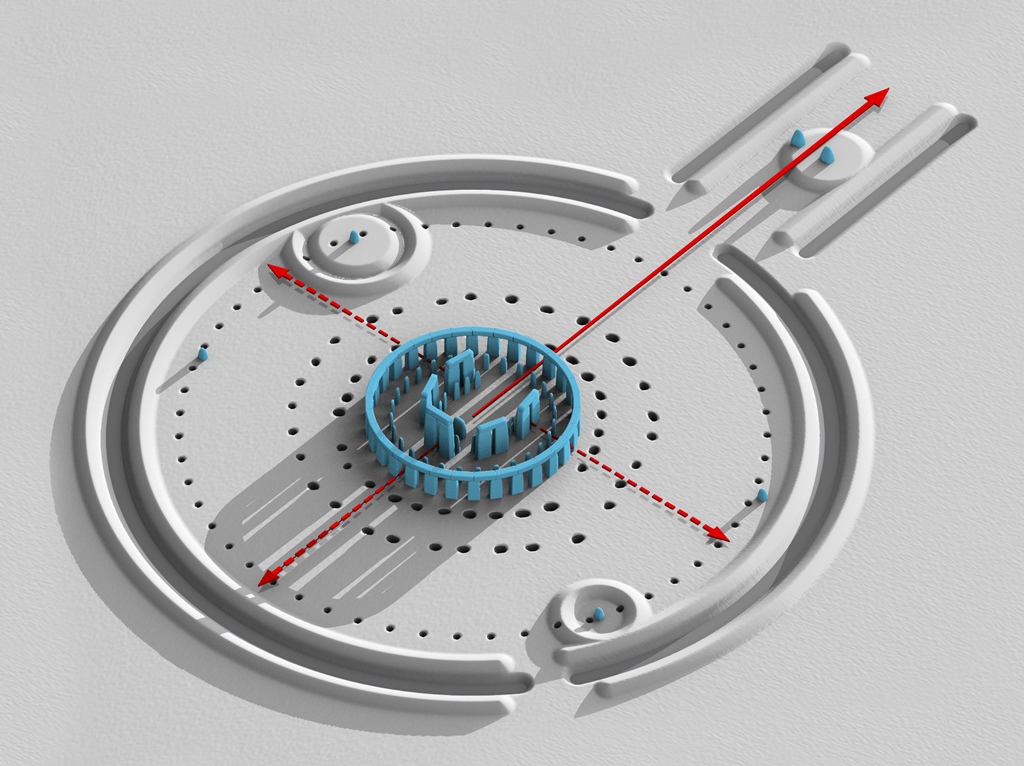

Stonehenge was not built as a single project with a master plan. Part of

the problem with figuring out the purpose of the structure might be that more

than one purpose may have come up over the course of its construction, which

evolved over a period of more than 1,500 years. The first phase of construction

was a large, circular ditch, about 360 feet in diameter, which can still be made

out today. There are two gaps in the ditch, probably to make entrances and

exits to and from the enclosed area easier. One gap is a small one, in the

south part of the circle. The other is larger, in the northeast, and appears to

have been the main access point to the site.

Stonehenge from South with Gap in Ditch

Stonehenge from Southeast with Ditch and Tourists

Stonehenge from Southwest with Ditch

Nella and Stonehenge from Northeast

Digging the ditch must have been a massive effort. The Salisbury Plain is

actually a plateau that is principally composed of chalk, underneath all the

greenery and topsoil. The builders of the ditch would have had to dig through

this using Stone Age tools, made from whatever materials were available. These

would have included things like stone (duh), bone, and deer antlers. Antlers

were apparently a popular tool, as many antler fragments have been found. And

one of the nice things about antlers is that they can be carbon dated. This

first phase of the construction took place around 3100 B.C. The obvious

purpose of such a ditch would have been as a defensive fortification, but

little is known about the people who built it, and this might be jumping to

conclusions. It is known that many human remains from around this period,

both cremated and uncremated, were found buried just within the perimeter

defined by the ditch, so the area seems to have been used as a kind of

cemetery for some period of time.

Around 500 years after the ditch, the builders started doing things with stone

around the center of the circle. The eventual result, accomplished over a

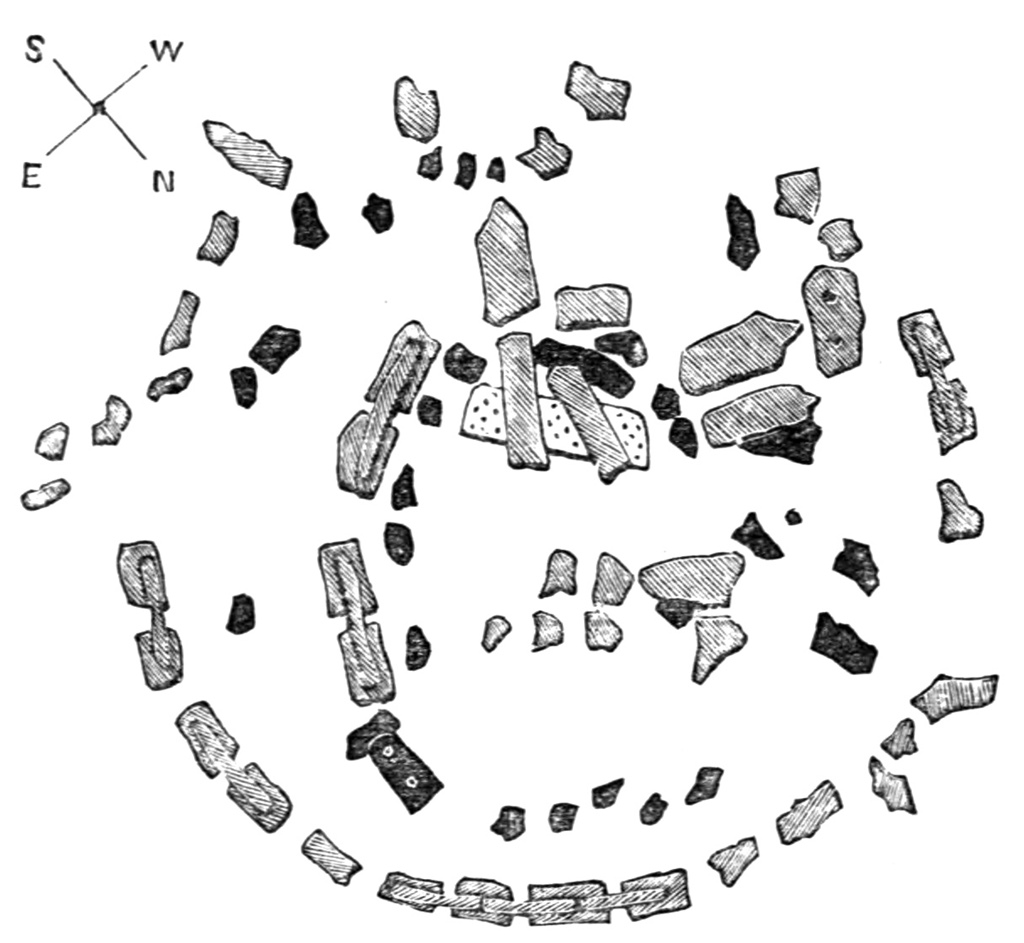

period of 1,000 years, probably looked something like this (viewed from the

south):

Layout of Stonehenge Site

When people think of "Stonehenge", they usually think of the stone construction

in the center of the ditch circle. But "henge" is technically a reference to the

enclosing ditch, though there are many henges in Britain with stone circles inside

of them. Stonehenge actually breaks some of the rules of the henge definition,

and is not considered a "true" henge. But for this page, I'll consider it to be

one anyway, because I find the stone circle much more interesting than the ditch.

Hopefully you feel the same, because most of the rest of this page is details

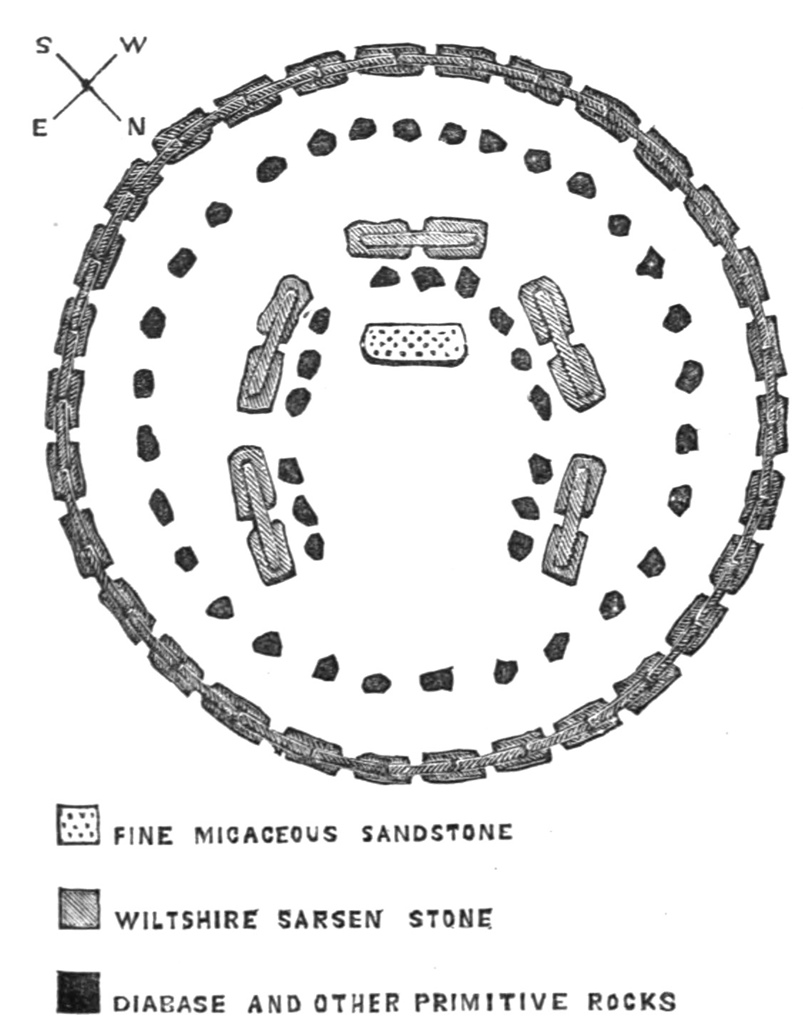

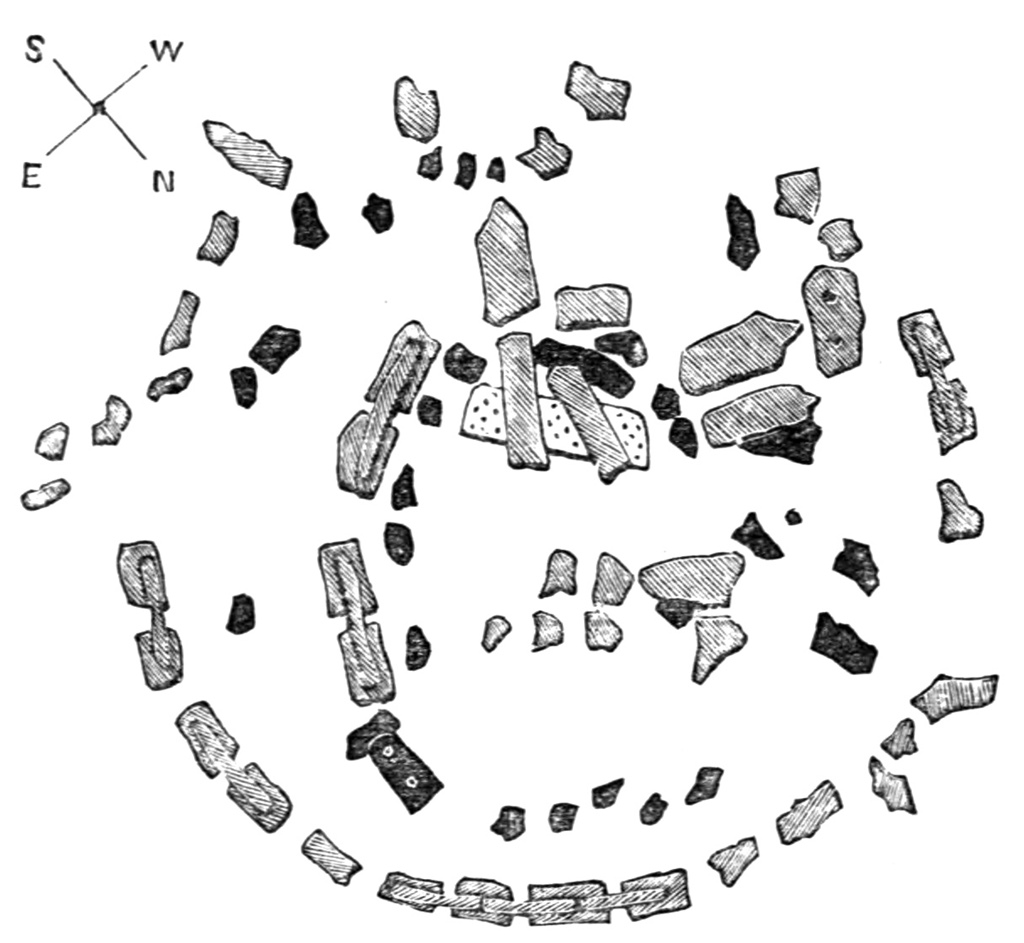

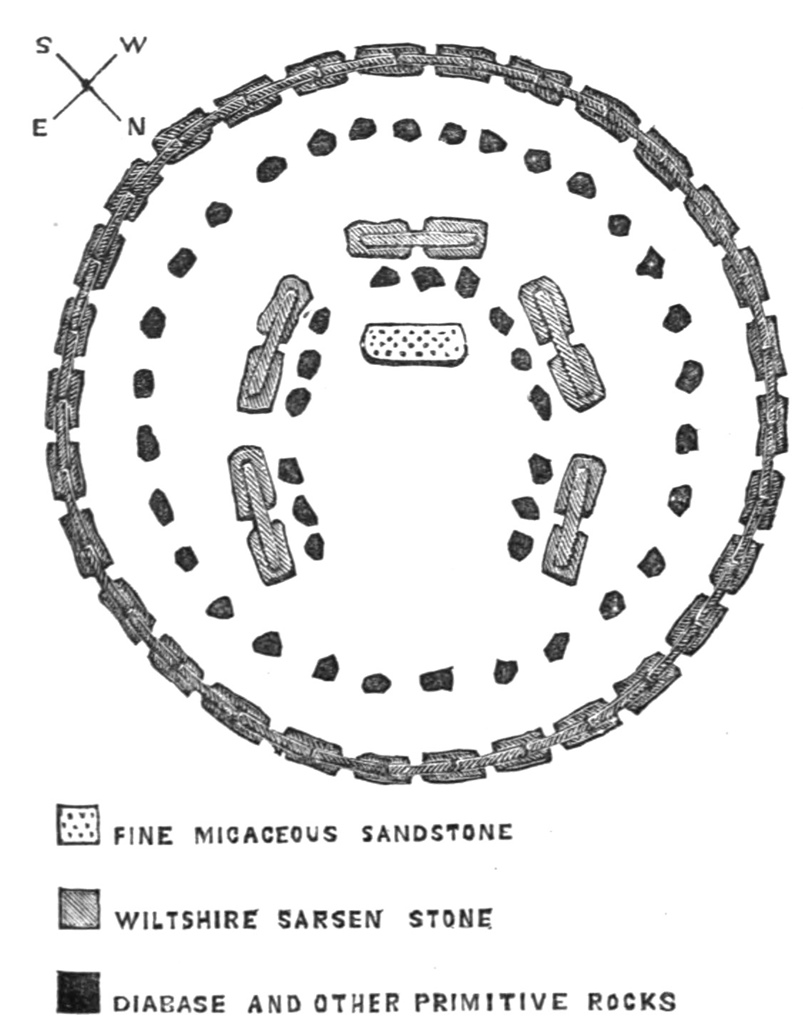

about it. Here's a picture of the probable one-time layout of the stone circle at

Stonehenge, and a picture of what it looks like now.

Original Stonehenge Layout (ca. 1600 B.C.)

Present-Day Stonehenge Layout

As you can see, Stonehenge isn't what it used to be. Over the past 3,600 years,

many of the stones have fallen over or have gone missing altogether (probably scavenged

whole or in pieces, for uses unknown). Stonehenge is made up of two basic types of

rock. The larger rocks, such as the ones that line the outside of the circle, are

called "sarsen stones", and are a type of local sandstone. The builders probably

wished they had been more local than they were, as they seem to have come from a quarry

25 miles away. Each of the stones is about 13 feet high and 7 feet wide and weighs

around 25 tons. There were originally 75 of them. 60 of them made up the outside

circle - 30 standing and 30 more acting as "lintels", bridging from one upright stone

to the next. The lintels were connected to the upright stones using "mortise and

tenon" joints, in which a "bump" (the tenon) is shaped at the top of each upright

stone to fit into a matching cavity (the mortise) which has been carved into a lintel

stone, sort of like a simple (but really heavy) Lego. In addition, the lintel stones

were joined to each other using a "tongue and groove" joint. Inside the stone circle

there were 15 more sarsen stones – ten uprights, arranged into a "horseshoe"

configuration, grouped into five pairs using five lintels.

Outer Sarsen Stones with Lintel

Inner Sarsen Stones with Lintel

Sarsen Stone with a Tenon Bump

Sarsen Stones

Sarsen Stones, Ditch and Highway

The other type of rock found at Stonehenge is referred to as "bluestone". This term

actually encompasses more than one type of rock, but they are all thought to have been

brought from what is now Pembrokeshire in western Wales, 150 miles away. They are

generally igneous rocks (and thus considerably harder than the sandstone sarsen

stones) and smaller and less uniform than the sarsen stones. They didn't appear to be

particulary blue, as far as I could tell, but just seemed as gray as everything else.

They weigh between 2 and 4 tons each, and there are thought to have been 80 of them

originally (43 remain on the site today). The bluestones were actually the first

stones introduced to the site, having been deployed around 2600 B.C. The sarsen

stones were added within the next couple of centuries, and nearly all of the changes

to the site after that consisted of rearrangements of the bluestones, which continued

until about 1600 B.C. Their final arrangement was as seen in the diagram above – a

circle of bluestones within the circle of sarsen stones, and a horseshoe of

bluestones within the horseshoe of sarsen stones. The stones weren't anchored very

well in their last rearrangement, as the bluestones that haven't disappeared

altogether have mostly fallen over.

Stonehenge from Northwest

A Bluestone

There is one stone that doesn't fit either of these categories. It's known as the

Altar Stone, and it's located within the head of the inner horseshoe. It's made

of a purplish-green micaceous sandstone, probably from Wales, and lies broken on

its side with one of the sarsen stones on top of it, having apparently fallen

there. It's not clear when it was introduced, or whether it was originally

upright. It's called the "Altar Stone" because of its location as an apparent

center of attention within the horseshoe, but its actual purpose is not known.

And of course the purpose of the whole apparatus isn't known either. There must

have been something going on – this was a lot of work for a lot of people.

Books have been written making complex astronomical claims about how the rocks

are arranged, and there is an alignment between the center of the circle,

a stone outside the circle (known as the "Heel Stone") and the sun which only

occurs at sunrise on the summer solstice. But additional books have been written

debunking most of the other claims.

The Heelstone

The inner horseshoe arrangement opens toward the henge entrance in the northeast,

making for an impressive approach for visitors. It seems like there must have

been some kind of ceremonial or religious significance, but while there were

three different groups of people involved in building or rearranging the stone

circle (one Stone Age group, two Bronze Age groups), none of them wrote down

anything about any of it. The lack of a written language probably had something

to do with this. And the lack of any definitive answers on these questions makes

it possible for people to come up with theories of their own, and there have been

many.

New Agey Types

Tourists and Stonehenge

Unable to come up with any new theories of our own on short notice, we finished

our loop around the henge and headed back toward the shuttle pickup point.

Stonehenge from Southeast

Stonehenge from Southeast with Tourists

Bob and Stonehenge from West

Nella and Stonehenge from West

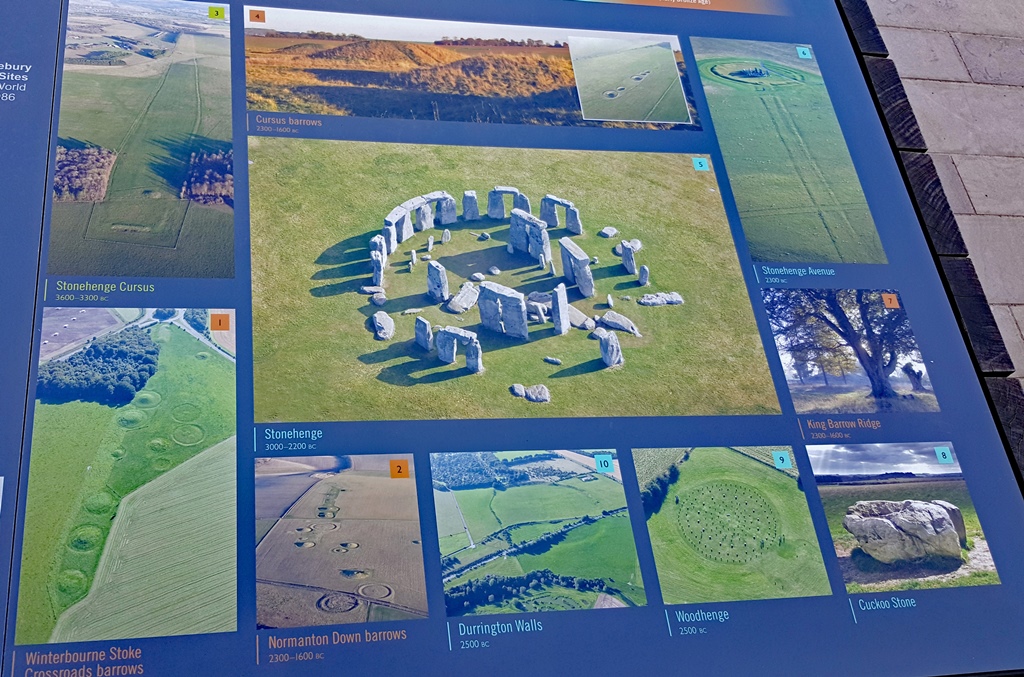

On the way, we had a good look at the adjoining fields, mainly agricultural, and we

could see some little hills in the distance. These were barrows, burial mounds

used by the locals during the period of Stonehenge's construction. There are many

of these in the area.

Fields with Sheep

Fields with Fences and Barrows

Landscape with Barrows

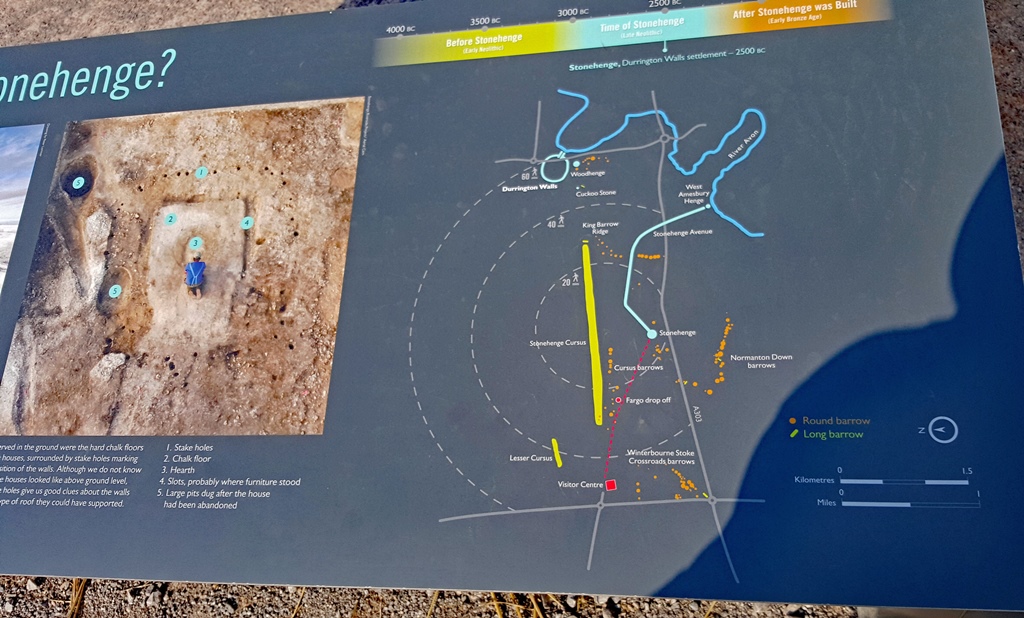

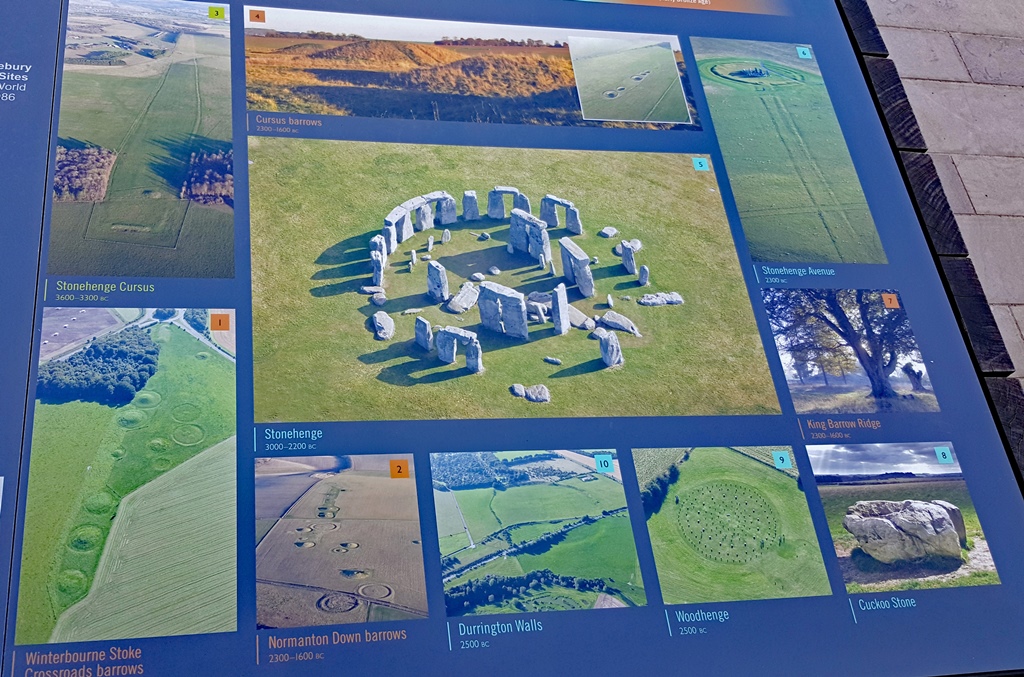

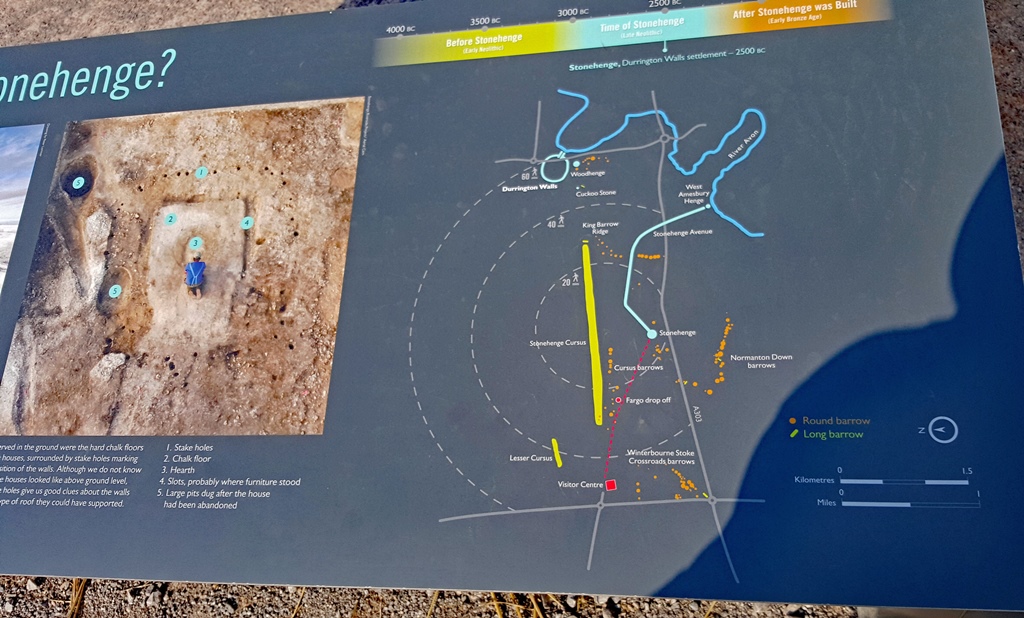

Back at the Visitor Centre, we had time to look at some outdoor exhibits.

Map of Area

Aerial Photographs

One exhibit was a guess at the types of huts the builders of Stonehenge may have

lived in. No remains of such huts have been found near Stonehenge, but these

were based on remains found at other nearby sites.

Reconstructions of Homes for Workers

Reconstructions of Homes for Workers

There were also exhibits attempting to answer the question of how Stone Age people

could possibly have moved all those gigantic rocks all of those miles. While

smaller than the sarsen stones, the bluestones still weighed in the multi-ton range,

and one might think moving them 150 miles would present unsurmountable problems for

people with Stone Age technology. But boats which are known to have existed at the

time could have handled much of the trip from Wales by sailing along the coast or on

the local rivers, and moving the stones overland could have been accomplished with a

sledge-and-roller strategy. In 1995, a group of 100 volunteers actually did move an

exact replica of one of the larger sarsen stones several miles using this

arrangement. And they were even able to set it up vertically in a hole they'd dug

by using an A-frame contraption they'd put together, all with Stone Age technology.

The replica stone is on exhibit outside the Visitor Centre, tied to the sledge and

rollers that were used.

Replica of a Sarsen Stone on Sledge and Rollers

We made it back to our tour bus and we began the long ride back to London, with

one last look at Stonehenge on the way. It's actually pretty close to the highway.

Stonehenge from Highway

We made it back to London in one piece and took the Underground back to our hotel.

We found some dinner and went to bed soon after – it had been a long day. But we

already had plans for the next day. We would be starting with a visit to St.

Paul's Cathedral.