The Brussels Musical Instruments Museum was established in 1877 as part of the

Brussels Royal Music Conservatory. Its original collection was already owned by

the Conservatory at that time, but was greatly expanded by its first curator, a

man named Victor-Charles Mahillon. Expanded enough so that it didn’t really fit

into the space that had originally been allocated for it. Buildings were expanded,

and others acquired to make space for storage, display and administration of the

collection, which grew further under succeeding curators. Eventually it was decided

that the museum was too fragmented, and in 1978 two buildings once owned by the Old

England department store were purchased for the museum. One of these buildings was

a neoclassical building on the Place Royale. But the building to be used for

display of the collection had been built in 1899 in the art-nouveau style according

to a design by architect Paul Saintenoy. The building had been vacated in 1972 and

had fallen into a certain amount of disrepair. But it was large enough for the

envisioned display space, and a careful restoration would make for a very attractive

building. This is eventually what happened, but it took awhile. The Musical

Instruments Museum (or "mim") in its present form was opened in the year 2000.

Building Exterior

Musical Notes

The displays in the museum mostly have placards describing them. There is

good news, in that the placards are bilingual. But the bad news is that

the languages are French and Dutch. Fortunately visitors are given audioguides

in chosen languages on entering, which describe some of the exhibits and in

some cases actually play examples of what the instruments sound like (some of

this is also available on the museum’s website).

And a good thing, as the sound and the description are often less than

obvious. We weren't allowed to keep the audioguides, though, so some of the

descriptions and captions below may be imprecise.

As we walked through the displays, we saw exactly what one would expect from a Musical

Instruments Museum – a large number of conventional musical instruments.

Wooden Flutes

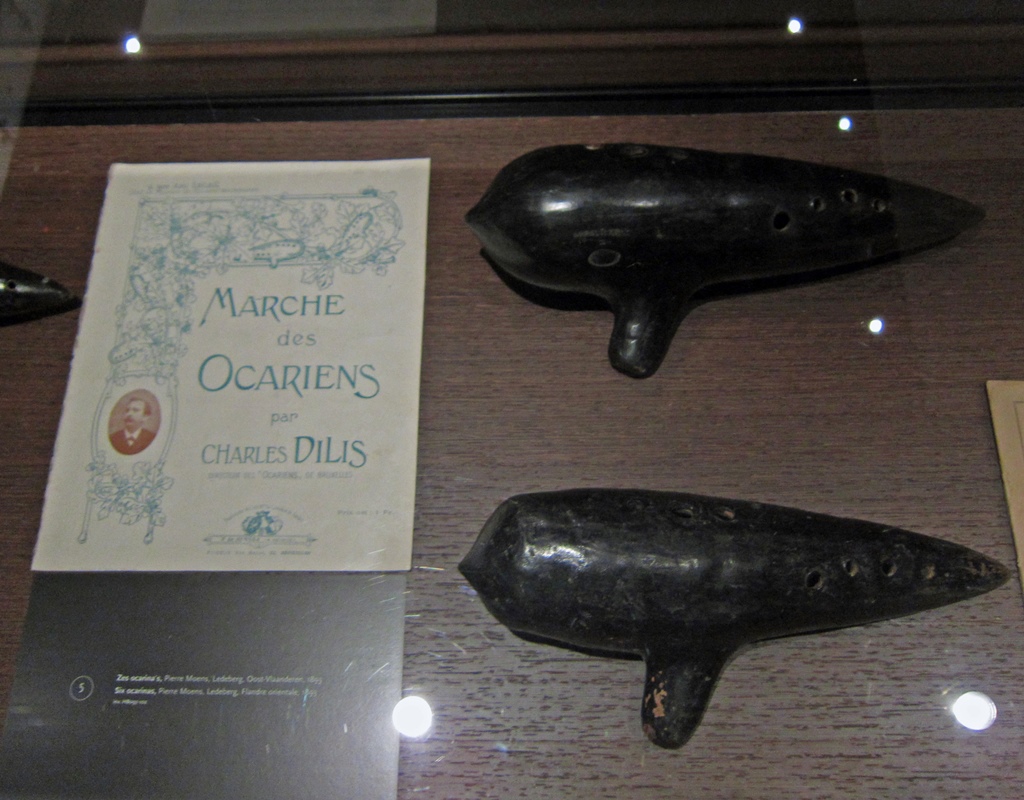

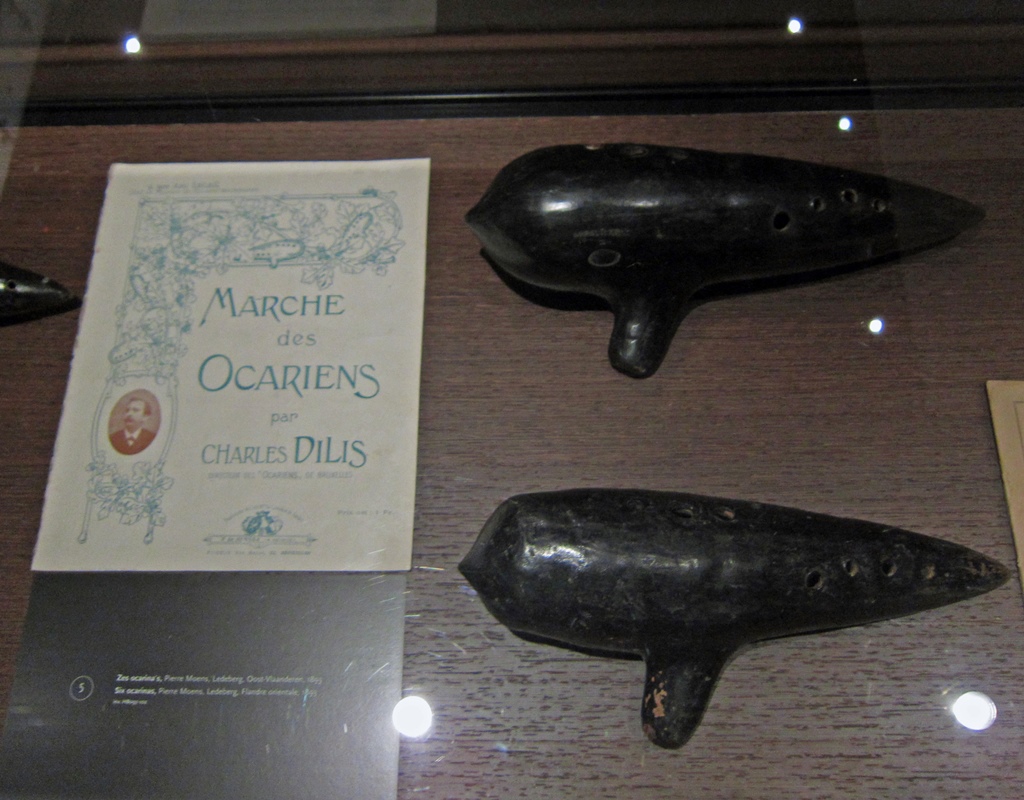

Ocarinas

Accordions

Italian Accordion

Tambourine

Bagpipe

Valved Horns

Connie and Clarinets

Guitars

Guitar

Violins, Violas, Cellos

Elaborate Violin

Instrument Repair Shop

But on closer inspection (and helpful descriptions from the audioguide), some of the

instruments were not exactly what they seemed to be. For example, the instrument

below, known as a "Hardanger fiddle", is a Norwegian instrument that appears to be

an elaborately decorated violin. This is partly true, but beneath the usual set of

strings there is a second set of strings that resonates with the melody strings to

produce a more complex sound (you can hear a short sample on

the website).

Hardanger Fiddle (Norway, 1812)

Some of the displayed instruments were reflective of the technology available at the

times in which they were created.

Synthesizer Equipment

Gramophones (ca. 1900)

Jeu de Trompettes, Paris (1828)

Componium, Amsterdam (1821)

Hurdy-Gurdy (Vielle à Roue, 18th C.)

Some such instruments were used for street entertainment. For example, the following

is a mechanically animated tableau called "The Dentist", that tells a comical and

highly politically incorrect story while music plays from the

barrel organ

on which it is mounted.

"The Dentist", Animated Barrel Organ Display (19th C.)

Other instruments looked unfamiliar, often because they were from another part of

the world or from an earlier time.

Épinettes (17th-20th C.)

Tibetan Instruments

Chinese Instruments

Chinese Bianqing

Yu in the Form of a Tiger (China)

Zither

Korean Zithers

Stringed Instrument with Gourds

Drums

Some instruments ranged from imaginative to just bizarre.

Fishy Guitar

???

Dragon-Fish Instrument

Ceramic Wind Instruments

Glass Horn

Wrap-Around Horn

Triple-Necked Guitar

Beer Can Instruments

One display had us puzzled for awhile, as there didn’t seem to be any possible

way to play it. There were some other instruments nearby called "serpents", which

were roughly tubular wind instruments that were bent in places so as to appear

snakelike. As it turned out, this display wasn’t an instrument at all, but rather

a chandelier made up of repurposed serpents.

Chandelier Made from Serpents (Early 19th C.)

The museum also displayed many keyboard instruments, some of which were also

works of visual art. There were several beautiful harpsichords, for

example. A harpsichord

makes sounds by plucking strings

inside of it when the keys are pressed, rather than striking them, as in

a piano. A virginal is a smaller, simpler variety of harpsichord.

Harpsichord (Hamburg, 1734)

Couchet Harpsichord (Antwerp, 1646)

Harpsichord (Toulouse, 1679)

Rectangular Virginal (Antwerp, 1548)

Harpsichord/Virginal (Antwerp, 1619)

Again we came across an instrument that wasn’t quite what it seemed. In this

case the instrument looked like another harpsichord, but was instead a Spanish

instrument called a Geigenwerk. This instrument is played by two people – the

one playing the keys, and another one who furiously turns a crank to keep wheels

inside the instrument spinning. When the keys are pressed, the strings inside

the instrument are brought into contact with the spinning wheels, resulting in

a violin-like "bowing" sound.

Geigenwerk (Spain, 1625)

There were other beautiful keyboard instruments as well, mainly pianos.

Piano of Queen Marie-Henriette (ca. 1865)

Piano (Brussels, 1840)

Piano (Dresden, 1793)

Piano (Ulm, 1780)

Player Piano (Germany, ca. 1900)

Wrap-Around Piano

Organ (Italy, 17th C.)

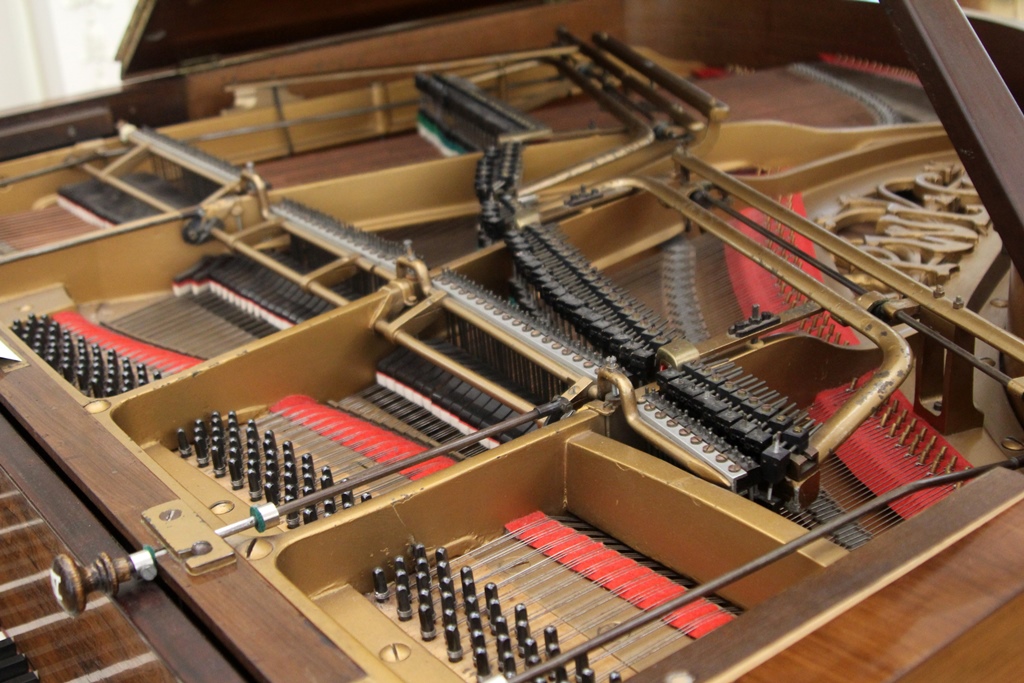

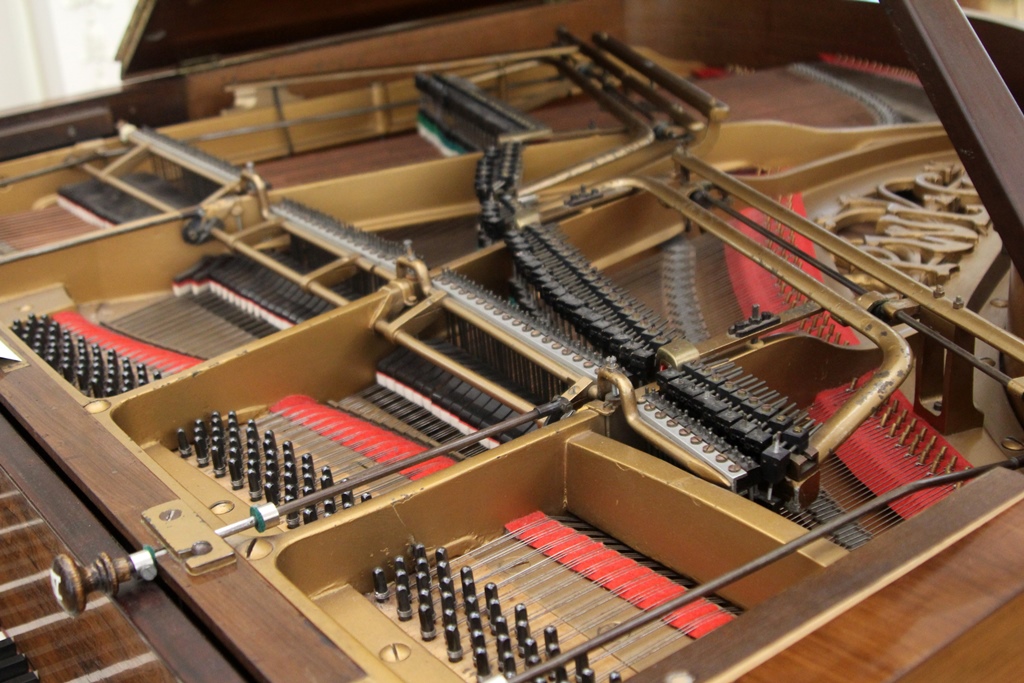

One piano had its top open to display an unusually complicated interior. This

is the only piano in the world that contains a functioning "luthéal" mechanism. The

luthéal mechanism, patented in 1919, can be placed inside a grand piano and adjusted

to change the timbre of the piano’s sound,

making it sound like other instruments

such as a harpsichord or a harp. In this age of electronic instruments this might

not sound that impressive, but at the time it was an impressive feat, being

accomplished solely by mechanical means.

Pleyel Grand Piano (1911) with "Luthéal" Mechanism

Innards of Piano with Luthéal Mechanism

Another piano caught our attention because it had two full keyboards. As it

turns out, the top keyboard is reversed, with low notes on the right and high

notes on the left. The idea was that a musician could play both high and low

notes with the same hand, making certain types of performances easier (if one

could get past the learning curve of mastering a backwards keyboard). Also,

it was possible to get more fingers on high notes or low notes at the same time, yielding

a sound density

usually only available in duets. Again, this is the only one of these in the world.

Double Piano with Mirrored Keyboards (Paris, 1878)

Finally, an instrument known as a "glass harmonica" was on display. This instrument

consists of a set of nested glass bowls, mounted on their side in a wooden cabinet

and free to spin like a lathe (through use of a foot pedal). Those who have run wet

fingers along the rim of a crystal wine glass can imagine the type of sound that is

produced by applying wet fingers to a glass harmonica. Multiple notes can be played

at once, depending on the number of fingers applied. After the instrument was introduced

in the late 18th Century, it was popular for a time, until people decided that it could

cause epileptic seizures. You can hear

a short selection

for yourself on the museum website if you’re so inclined, but don’t say you weren’t warned.

"Glass Harmonica" (Germany, late 18th C.)

After looking at the instruments, we went upstairs, past a small concert hall

to the bar at the top of the building. We weren’t thirsty, but we were

interested in the view of the Lower Town.

Lower Town from Bar

This completed our visit to the Musical Instruments Museum, and we headed back

down the hill to the Lower Town. On the way we passed an interesting looking

clock, to the right of the Albertina Park, known as the Clock of Citizens. This

clock is a Jacquemart clock, meaning there’s a figure at the top that strikes a

bell, and there are twelve other figures mounted in the wall around the clock face,

each pointed to by an hour. The clock was built in 1959 for the Brussels

World’s Fair.

Jacquemart Clock

We returned to the hotel and relaxed for awhile, eventually going out and

getting some dinner. We returned to the hotel by way of the chocolate

store installed in its ground level.

Chocopolis

We tried some of the chocolate but weren’t that impressed. Maybe we selected

poorly. We resolved to resume our quest for Belgian chocolate later. If we

were to find it the next day, we’d have to find it in another city, though,

as we were planning to take a trip to the city of Bruges.