St. Patrick's Cathedral

The

National Cathedral and Collegiate Church of Saint Patrick

is the largest church

in Ireland and the National Cathedral for the Church of Ireland. It is situated in

a fork of the River Poddle (now underground), and is thought to be next to a well

used for baptisms in the 5th Century by St. Patrick. During the 1901 construction

of the garden next to the cathedral, six Celtic grave slabs dating to the 10th

Century were found. One of the slabs was covering the remains of an ancient well,

and it's thought that this may have been the very well used by the Saint.

Garden Fountain

9th-11th Century Grave Marker

The church was founded in 1191, but the building from which the present one

evolved was built in the early-mid 13th Century. Over the centuries there have

been additions and collapses and fires and even floods (the water table is only

7 feet below the floor of the cathedral, making a crypt out of the question).

In the 17th Century, Oliver Cromwell stabled horses in the cathedral nave. But

all the periods of deterioration have been followed by restorations, with the

most recent big one coming courtesy of the Guinness family – mainly Benjamin

Lee Guinness, whose badly-needed 1860-65 restoration was done under the condition

that it not be interfered with. Many things were done during this restoration,

including the addition of a ceiling (separate from the underside of the roof) and

the removal of wooden partitions which separated parts of the church from each

other. Eventual reviews of the work were not unanimous, but the cathedral board

must not have been too upset – the cathedral was reopened in 1865 with an

elaborate ceremony, and a bronze statue of Sir Benjamin was put up outside the

south side of the cathedral in 1875.

The south side of the cathedral is also where we found the entrance. We paid the

admission fee (regular maintenance is now done with the help of these fees) and

walked in. To our left we couldn't help but notice a tall, dark-colored monument

against the wall (the Boyle monument – more on this later), and, in front of us,

a small gift shop (also to help with the maintenance expenses, no doubt).

Bob, Boyle Monument, Gift Shop

To the right was the bulk of the cathedral. We set off to explore.

The Nave

Main Altar and Choir

Pulpit

Staircase to Organ Loft

Main Altar

Near the front of the church, looking to our left up the north transept,

we noticed several flags hanging from the wall. Apparently the north

transept was set aside in the 19th Century to commemorate Irishmen who

died in the service of the British army, and the flags are regimental

flags representing some of the soldiers. Some of the flags are more than

100 years old.

Regimental Flags, North Transept

There were also flags hanging from the walls of the choir, in front

of us. These flags are family heralds representing membership in the

Most Illustrious Order of the Knights of Saint Patrick. This was an

order of chivalry founded in 1783 under King George III. In 1869,

ceremonies related to the order were moved to Dublin Castle, and the

flags above the choir stalls in St. Patrick's represent the order's

membership at that time. The order pretty much faded away after

Ireland gained independence from Britain, though technically Queen

Elizabeth II is still a member.

Choir

Choir

Behind the high altar we could see into a large chapel that was not open

for visitors. There were two men in the chapel who seemed to be brainstorming

something. We found out afterward that this was the Lady Chapel – a chapel

dedicated to the Virgin Mary (a Lady Chapel is apparently a common practice

among large Northern European cathedrals). For a while the St. Patrick's

Lady Chapel was known as the "French Chapel", as it was long used by French

Huguenots who had fled France for Dublin to escape persecution. As it turns

out, the Lady Chapel was closed for a major renovation shortly after our

visit – the two men may have been discussing the plans for the project. The

Lady Chapel is now open to visitors, and appears to be gorgeous, based on

pictures posted on the Internet.

Lady Chapel

As with most European cathedrals, St. Patrick's is filled with burial

places and monuments to the departed. One such monument, shown above, is

the Boyle Monument, put up in 1632 by Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork.

It was originally set up against the east wall of the choir, but some were

offended by its conspicuousness (including Lord Deputy Wentworth and

Archbishop William Laud), and it was taken down in 1634, to be rebuilt

against the south wall of the chancel. This was not taken well by the

Earl, who already despised Wentworth for other reasons (e.g. property

confiscation). But he must have felt somewhat vindicated when Wentworth

was later tried, convicted and beheaded for treason following the Irish

Rebellion of 1641. In 1863, during the Guinness renovation, the monument

was moved again, this time to the west end of the cathedral, where it

remains to the present day. As an aside, one of the many figures depicted

on the monument (the one in the middle, on the lower level) is a rendering

of the Earl's youngest son Robert (the Earl and his wife, Lady Catherine,

had 14 children), who grew up to publish a fundamental law dealing with

the pressure and volume of gases (now known as Boyle's Law) in 1662. This

law is so significant that the younger Boyle is sometimes referred to as

the Father of Modern Chemistry.

Not far from the Boyle Monument is the stylistically similar memorial to

Thomas Jones, who served, among other positions, as Dean of St. Patrick's

Cathedral, Archbishop of Dublin and Lord Chancellor of Ireland. He died

in 1619.

Memorial to Thomas Jones

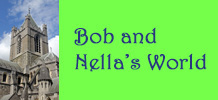

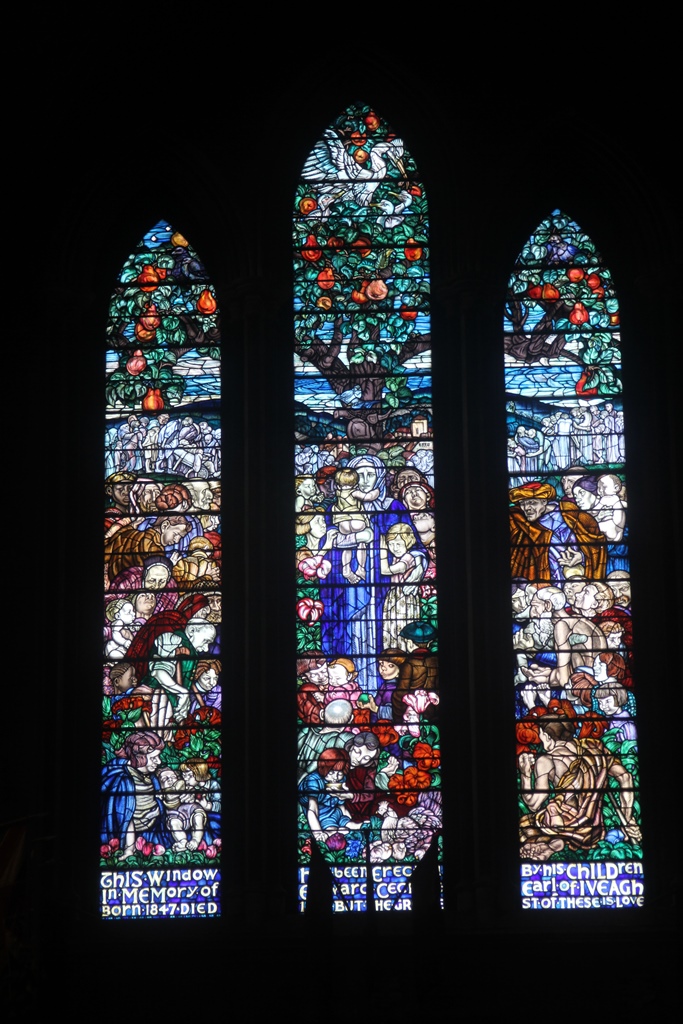

Not all of the memorials in the cathedral involve statuary. For example, the

memorial to Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh (1847-1927), consists of a set

of stained-glass windows. Edward was the third son of Sir Benjamin Guinness

(the Guinness behind the 1860-65 restoration), and had an active and rewarding

career of his own. He was the chief executive of Guinness from 1868 until

1889, during which the output of the brewery increased enormously. He took

over sole ownership of the company in 1876 by buying out his brother, and when

he floated two-thirds of the company in 1886, he became the richest man in

Ireland. He was a generous philanthropist, contributing heavily to slum

clearance (including one just to the north of St. Patrick's, which he

transformed into the park seen there today) and housing projects, in addition

to medical research and the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-09 (Mount

Iveagh in Antarctica is named in his honor). He acted as High Sheriff of

County Dublin in 1885 and attained a seat in the British House of Lords in

1891. He participated in the 1917-18 Irish Convention that tried

(unsuccessfully) to find a moderate solution to the demands of Irish

nationalists, and was a personal friend of W.T. Cosgrave, who became the first

leader of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Windows in Memory of Edward Guinness

Another non-statue is a cross which was put up in memory of Sir Samuel

Ferguson (1810-1886), a barrister, antiquarian (he studied megaliths and

other archeological sites) and keeper of public records. He married into

the banking branch of the Guinness family, but is probably best

remembered as a poet, in which capacity he is considered an important

forerunner of such poets as William Butler Yeats.

Cross in Remembrance of Samuel Ferguson

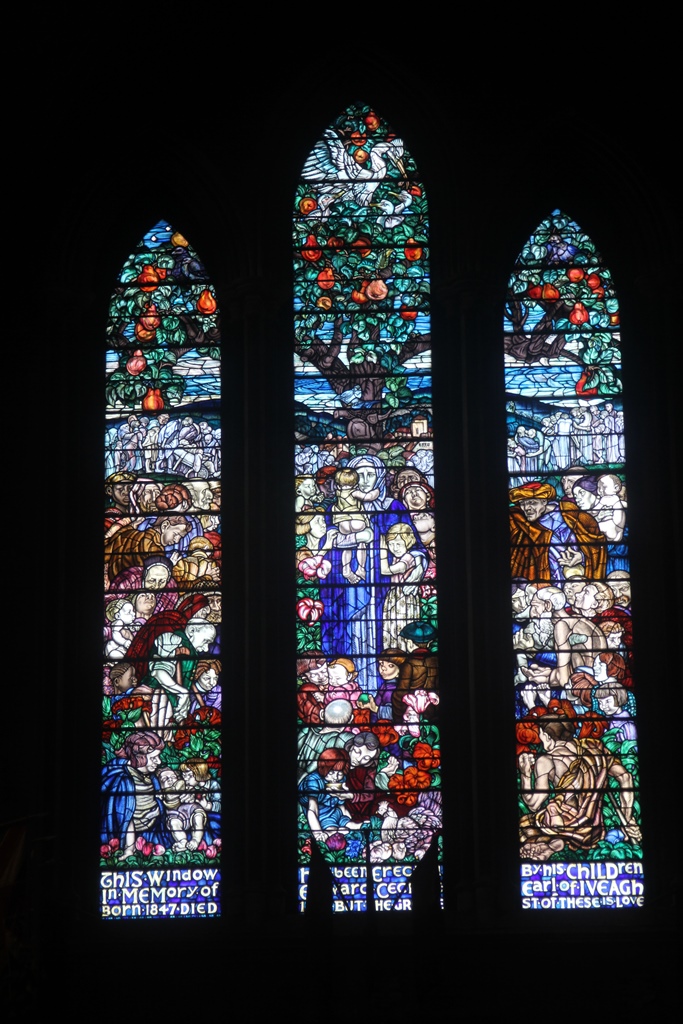

But getting back to statues, the northern gallery of the cathedral is filled

with them. The most elaborate one is probably the memorial to George Nugent

Temple Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham (1753-1813). George was a political

creature, attaining a seat in the House of Commons at an early age and being

briefly appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1782. While Lord Lieutenant, he

supported increased legislative independence for Ireland, and it was he who

created the Order of Saint Patrick. He returned to British politics at the end

of 1783 but returned to the Lord Lieutenant office in 1787, which he held for

two years. But this second tour of duty was much less successful than the

first, as he made some missteps which made him thoroughly unpopular. When he

left office in 1789, he pretty much stayed out of politics for the rest of his

life. He didn't know any Guinnesses.

Side Gallery with Statues

Row of Statues

Statue of George Grenville Nugent Temple

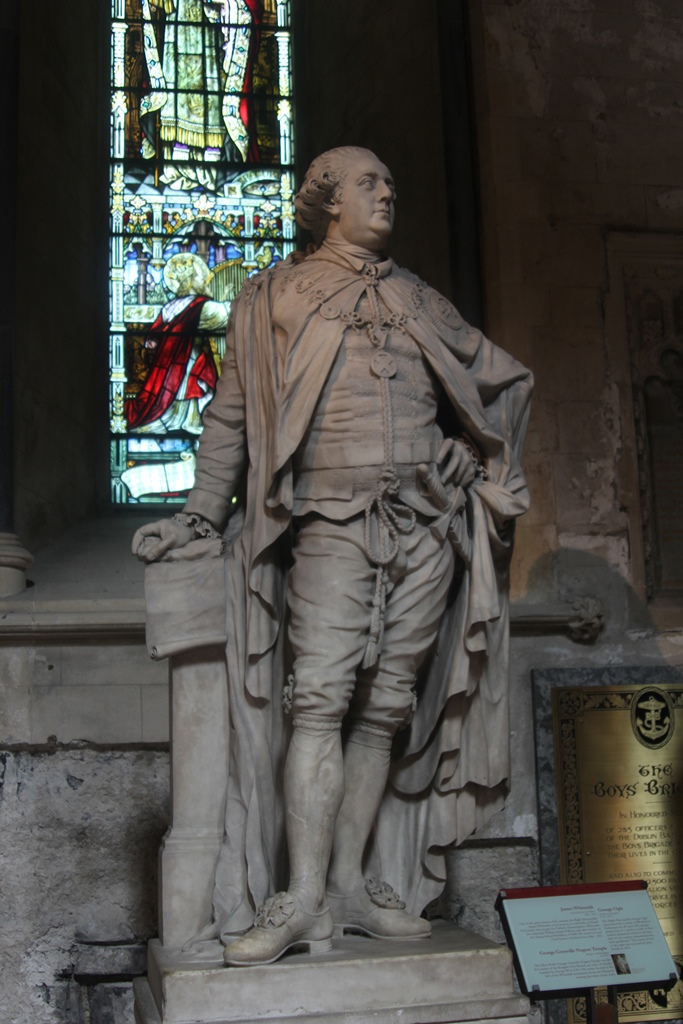

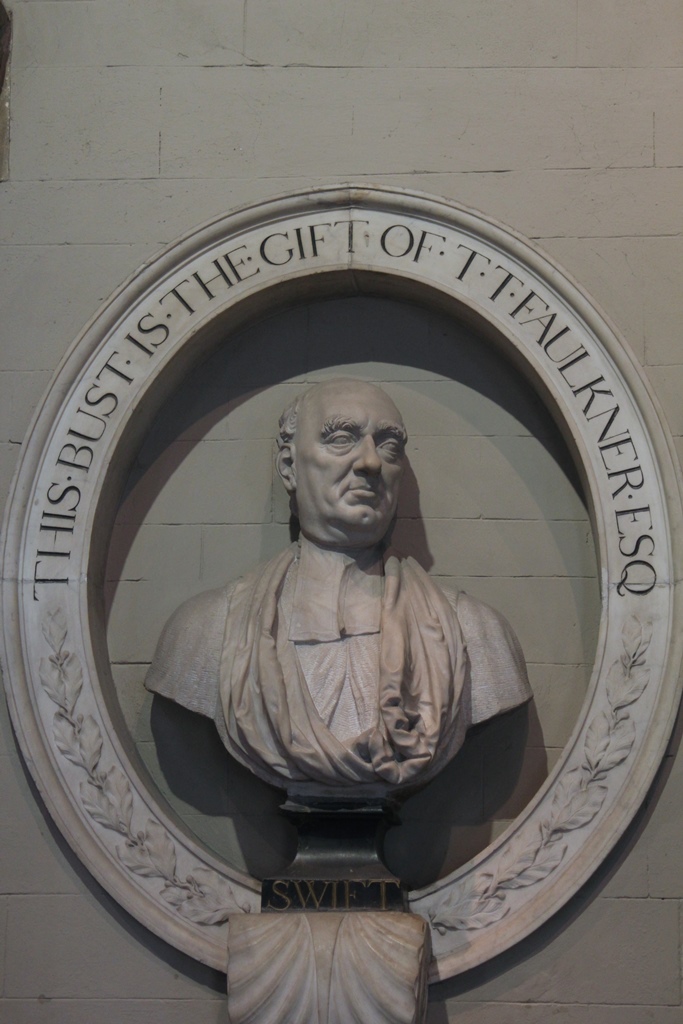

The most well-known person buried in the church is probably Jonathan Swift, who

served as the cathedral's Dean from 1713 until his death in 1745. Swift was a

prolific writer of prose, poetry, political tracts and miscellaneous

correspondence. Among his output were several works of satire, the most famous

of which was (and is) Gulliver's Travels, published in 1726.

Gulliver's Travels, written under the pseudonym "Lemuel Gulliver" (many

of his works were published under pen names), is about a young man who travels

(mostly accidentally) to many amazing places. Among these places are Lilliput

(where the people are under six inches tall), Brobdingnag (where the people are

above 70 feet tall), Laputa (a flying island), Glubbdubdrib (where Gulliver

talks to ghosts of historical figures), and the Country of the Houyhnhnms

(intelligent, talking horses, who rule stupid, deformed humans called Yahoos).

Oh, and Japan. Swift's satirical works tend to be difficult for modern-day

readers to understand as satire, as they often relate to now-obscure incidents

specific to the time in which they were written. But Gulliver's Travels

can be taken at face value as an imaginative fantasy, and people continue to

read it (and make movies of it) into the 21st Century.

Jonathan Swift is not buried alone in St. Patrick's Cathedral. He apparently

never married, but through much of his life he had a strong connection with a

woman named Esther Johnson. Swift first met Esther when he was a young man

working in England as a secretary. Esther was then eight years old, the

daughter of a woman who was acting as a companion to Swift's employer's sister.

Swift acted as Esther's tutor and mentor, and conferred upon her the nickname

"Stella". Years later, when Swift was working in Ireland and Esther had

reached the age of 20, Swift took a trip to England and brought back Esther

and Rebecca Dingley, another friend he had made while working for his former

employer. It's not clear exactly what the relationship was between Swift and

Esther. Some thought they'd been secretly married, but others thought the idea

preposterous. Esther lived with Rebecca throughout her years in Ireland, and

Swift formed and broke attachments with other women. But throughout this time,

Swift was a frequent visitor (always with Rebecca present) and correspondent

to Stella, and there is one incident in which Swift tried to discourage a

friend who was interested in marrying Esther (it's not clear whether the friend

went through with a proposal, but he ended up marrying someone else two years

later). Esther eventually died at the age of 47, and Swift was inconsolable at

this time. When Swift himself died 17 years later, he was buried next to her

in St. Patrick's Cathedral, at his request.

Bust of Jonathan Swift

Grave Markers of Jonathan Swift and "Stella"

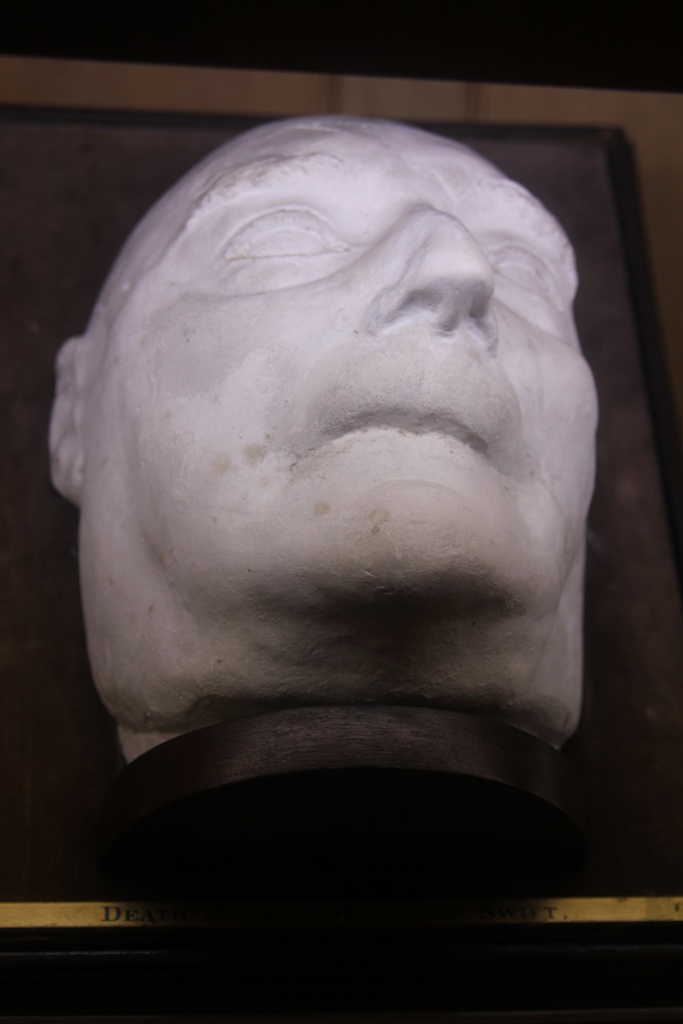

Death Mask of Jonathan Swift

We exited St. Patrick's Cathedral and headed in an eastward direction.

Our next destination for the day was to be the archaeology facility of

the National Museum of Ireland.