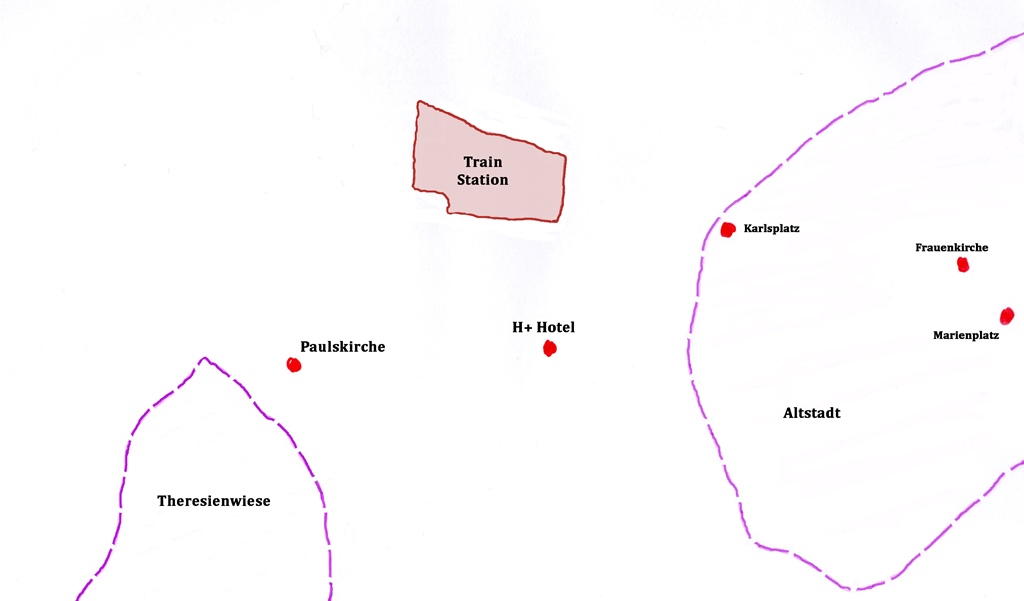

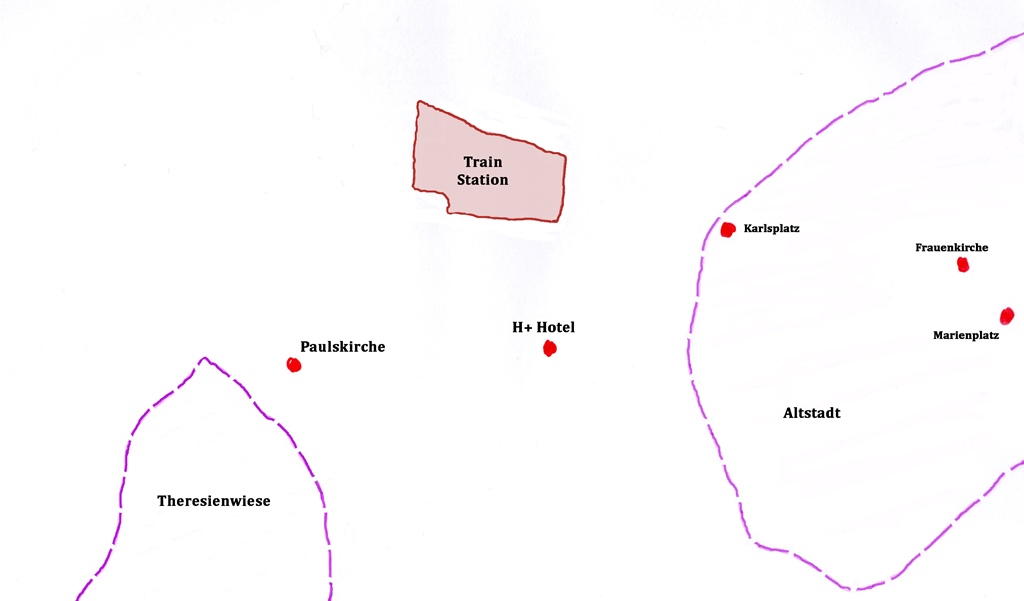

Southern Germany

Munich is the capital and most populous city (more than 1.5 million) of the German state of Bavaria.

It’s considered to have the strongest economy of any city in Germany, with major contributions coming

from manufacturing (BMW and Siemens AG are headquartered here, among other large companies), finance

(second only to Frankfurt in the country, with strength coming from banking and insurance) and media

(the largest publishing city in Europe). Munich is also a cultural center, with many respected art

museums and musical venues which have played host to many well-known composers and conductors over

the centuries.

Going back many more centuries, to the Bronze Age, evidence has been found that Munich’s river, the

Isar (which flows northward through Munich on its way to meet the Danube), was used as a trade route,

along which trade goods were floated on rafts, and that the area around present-day Munich was one of

the largest raft ports in Europe.

Moving forward a couple of thousand years, a small monastic settlement had established itself on the

Isar, and in the 8th Century it had acquired the name zu den Munichen (to the Monks), which

eventually was shortened and modernized into its present-day German name of München. But

Munich was not founded as an actual city until around 1158, when Henry the Lion, Duke of Bavaria,

made it so. Henry (who was born around 1129 in Ravensburg, of all places), a member of the House of

Welf (sometimes called Guelf), acquired the territory of Bavaria in 1156 through a decision

by Friedrich Barbarossa (Italian for “red beard”), the Holy Roman Emperor. Or rather reacquired the

territory, which had been taken away from his father (Henry the Proud) by King Conrad III of Germany.

It’s complicated.

Henry the Lion

Friedrich Barbarossa

Anyway, Henry (the Lion) loyally supported Barbarossa in various battles to maintain the

Imperial Crown, and remained in good standing with him. Until 1174, that is, when preoccupation

with securing his own borders led to Henry not supporting Friedrich in an invasion of Lombardy.

This invasion ultimately failed, and Barbarossa was royally displeased with Henry. Various

German princes who were unfriendly to Henry gleefully poured fuel on this fire, and eventually

Henry was stripped of his lands by the Emperor for insubordination, in 1180.

Barbarossa replaced Henry as Duke of Bavaria with Otto VI, Count Palatine of Bavaria. As Otto

was the first from his family to be Duke of Bavaria, he was now called Duke Otto I, from the

House of Wittelsbach.

Duke Otto I Wittelsbach

Otto would not be the last Wittelsbach to rule Bavaria, though. Over the ensuing centuries,

Wittelsbachs became members of royal houses all over the European continent, becoming kings,

dukes, electors, and even a couple of Holy Roman Emperors. But in Bavaria, Wittelsbachs ruled

as dukes, electors and kings (Bavaria became a kingdom in 1806 with the dissolution by Napoleon

of the Holy Roman Empire) from 1180 all the way until the closing days of World War I, with the

abdication of King Ludwig III in 1918 (738 years of Wittelsbachs, for those keeping score).

Ludwig III

And most of them made Munich their home. There are still several Wittelsbachs living in

various places across Europe, and the head of the family (currently Franz, Duke of Bavaria,

Ludwig’s great-grandson) still uses the Nymphenburg Palace in western Munich as a home and

office.

Nymphenburg Palace

If the Wittelsbachs thought that resigning the Bavaria monarchy in 1918 would calm things down,

they miscalculated rather badly. It may have rescued them from being treated like the Romanovs

in Russia, but resulted in political chaos in Munich. An attempt at a republic failed when its

leading proponent was assassinated. Then an attempted seizure of the government by a Communist

group also ultimately failed when the Communists were unable to deliver on any of their

promises and irreconcilable factions broke out in their ranks. Eventually a more right-wing

republic took hold which was more in tune with the Weimar Republic which had been established

in Berlin. In 1923 a group of members of the new National Socialist (i.e. Nazi) party, led by

Adolf Hitler, attempted an armed takeover of the government in a Munich action known as the

“Beer Hall Putsch”, which failed and landed much of the Nazi leadership in jail.

Beer Hall Putsch

In a well-publicized trial, Hitler was sentenced to five years but only served nine months,

during which time he dictated his book Mein Kampf. On his release, he resolved to

pursue his goals from within the existing political system. In a badly damaged post-war

Germany, his scapegoating of Communists and Jews found a receptive audience, and the rest is

an exceptionally ugly piece of history.

Munich played some key roles in this history. For one, this was the place where the

accurately named but not very effective Munich Agreement was concluded in September of 1938.

In this agreement, the United Kingdom and France agreed that Germany could annex the

Sudetenland (the ethnically German portion of Czechoslovakia) in exchange for Hitler’s

promise that he would not exercise any further territorial ambitions.

Munich Agreement Participants

However, within six months Germany had absorbed the rest of Czechoslovakia, and six months

later had invaded Poland (along with the Soviet Union), and World War II was off and running.

Ever since, the Munich Agreement has been synonymous with “appeasement” and has been used as an

argument for the futility of pursuing agreements with dictators.

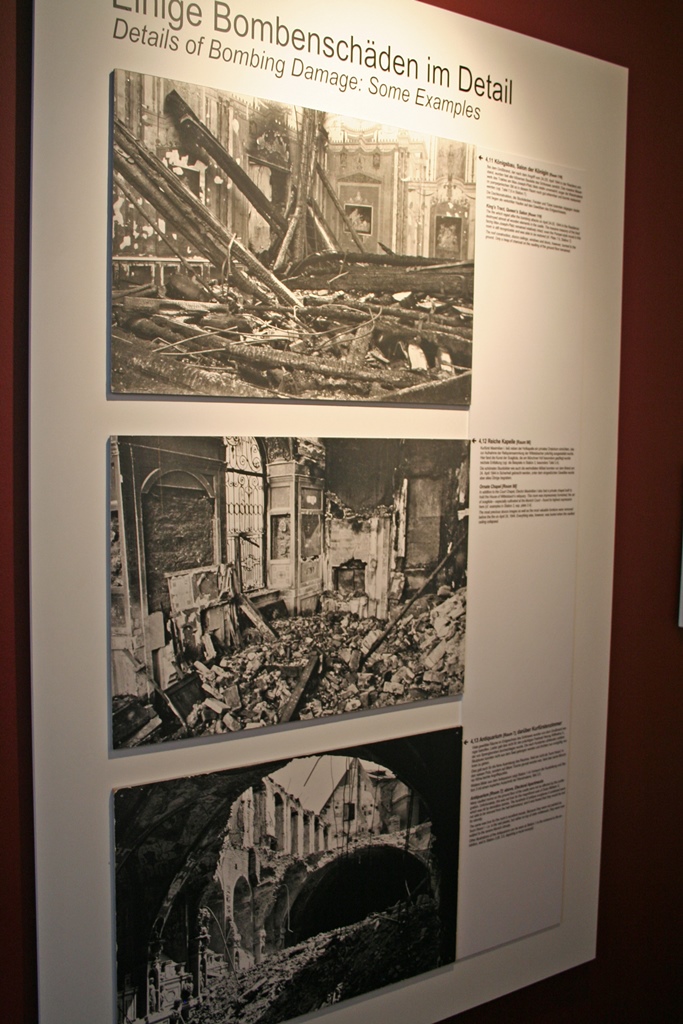

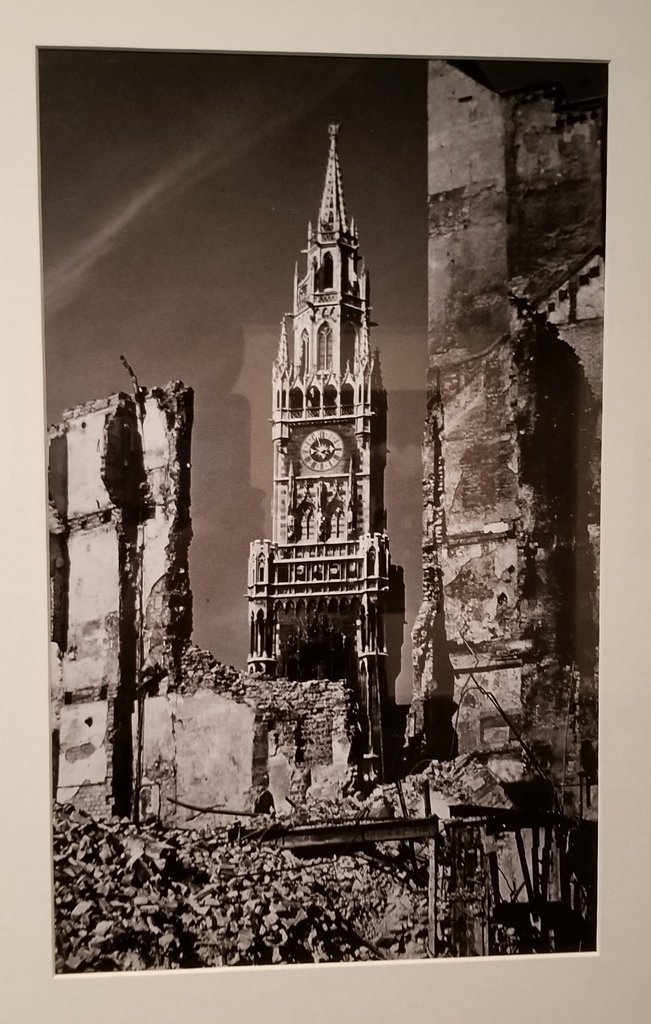

In addition, Munich remained the headquarters for the Nazi Party and for a number of

governmental administrative functions, and the site of a certain amount of manufacturing, and

when they were able (mostly after 1943), the Allies made a point of bombing Holy Hell out of it.

More than 70 air raids were conducted against Munich, resulting in more than 22,000 people being

killed or wounded and more than 81,000 homes being damaged or destroyed. About 90% of the

city’s Old Town area was severely damaged.

Bombing Damage

Bombing Damage

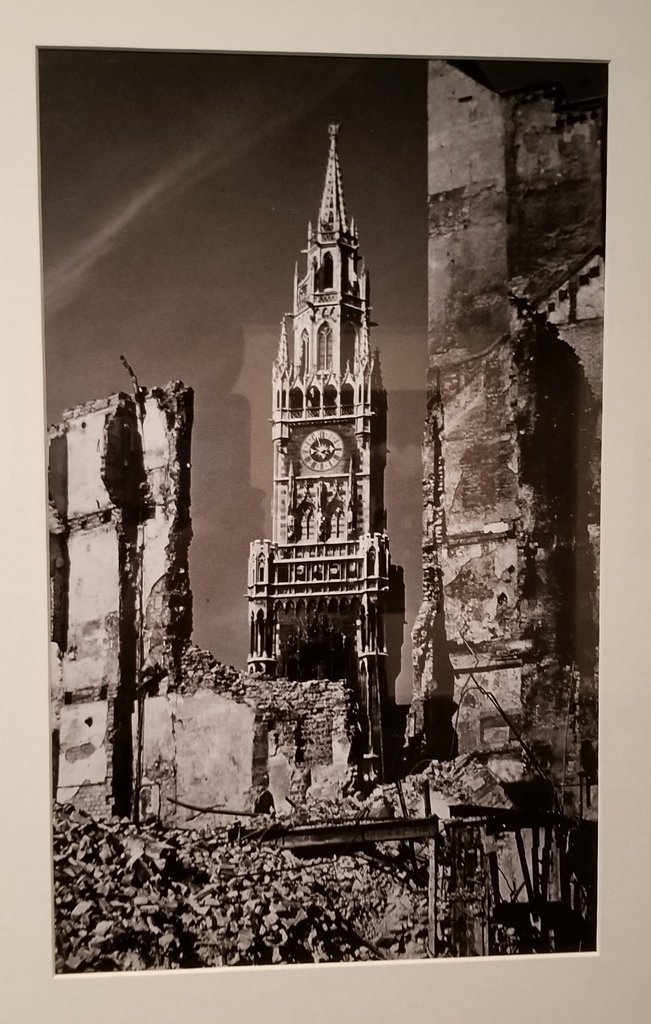

After the war, Germany was divided into occupation zones which were occupied for a time by

armed forces of assigned Allied countries, and most of Bavaria (including Munich) was part of

a U.S.-occupied zone. In 1949, after a great deal of haggling, all of the zones except those

under Soviet occupation were combined into the Federal Republic of Germany (AKA West Germany),

while the Soviets maintained control of their zone as the German Democratic Republic (East

Germany). This division remained in place until 1990, when Germany was reunified as a single

country.

Occupation Zones

Post-war recovery began soon after the end of the war, both in Germany and in many other

European countries (both Axis and Allied), but was faster in some places than in others.

Economies had to be rebuilt, both in terms of infrastructure and in modernization of business

practices. Cooperation among some of the countries materialized, with trade barriers being

reduced and a certain amount of aid being provided by countries which had received less

damage (particularly the U.S. and Canada). Reconstruction was begun, with some cities

modernizing areas which had been devastated and others opting to rebuild some of these areas

much as they were before the war. Munich did some of both, but resolved to rebuild the Old

Town area to recapture its former grandeur.

The rebuilding of Munich was slow, meticulous and expensive, but by the 1960’s the city felt

it had recovered enough to make a bid to host the 1972 Summer Olympics. The bid was

successful, and in 1972 the world’s best athletes and hordes of spectators (and media)

converged on Munich.

1972 Olympics

As usual, the 1972 Olympics were memorable from an athletic standpoint (this was the

Olympics when U.S. swimmer Mark Spitz won seven gold medals, for instance), but will sadly

always be remembered for the Olympic Massacre, in which 11 Israeli athletes and a German

policeman were murdered by Palestinian terrorists.

Worldwide reactions to this crime were various and complicated, but Munich and the Olympics

mainly responded by improving their security measures for future events. In Munich, the

post-war recovery continued, and has been generally successful. Munich has become a popular

tourist destination – for the most part, visitors are not so concerned about security, but are

far more interested in things like Oktoberfest.

Oktoberfest, of course, is the widely-copied folk festival that takes place in Munich each

year. It runs from mid-September or so until sometime around the first Sunday in October,

and is centered around several tents (currently 34 of them) which are annually put up in a

fairground called the Theresienwiese. The Oktoberfest began in 1810, when there was

a big party to celebrate the wedding of Wittelsbach Crown Prince Ludwig (later King Ludwig I)

to Princess Therese of Saxe-Hildburghausen on October 12 (the fairground is named for the

Princess – her first name, not the Saxe-Hildburghausen part).

King Ludwig I

Queen Therese

There have been ceremonies and festivities of various types over the years (there was a

horse race until 1960), and the cuisine has evolved over time as well. Mainstays these

days include sausages, gigantic pretzels (with mustard, please), and lots and lots of beer

(6.7 million liters served in 2013, for example). All of the beer served must conform to

the Reinheitsgebot quality standards and must be brewed within Munich’s city limits.

Munich Signpost

Our visit to Munich happened in May, so we missed Oktoberfest by a wide margin, but the basic

cuisine can be found in Munich throughout the year. We enjoyed it very much, but only Connie

sampled the beer, as Nella and I don’t drink the stuff. Connie seemed to give it an

enthusiastic thumbs-up.

Connie with Beer and Pretzel

If you’re a reader of a particular priority-set, you might be asking yourself the question,

“Why would you go to Munich if you don’t drink beer? Whatever would you do with yourself?”

You also might be pointing out that that’s actually two questions. Regardless, the

question(s) is/are outnumbered by the answers, some of which will appear in this page and

others in the pages to come. It’s probably best to begin at the beginning, which in this

case is in Ravensburg.

The day started with our hosts in Weingarten, the Nuhns, taking us and our luggage for the

short drive from their house to the train station in Ravensburg. We’d had a great time

with them (see Weingarten pages for details), but it was time for us to move on to Munich

and let them get back to their regular lives.

Green Tower En Route to Ravensburg Station

In Ravensburg we caught a regional train up to Ulm, where we transferred to a faster and

cushier Intercity train which took us the rest of the way to Munich.

On the Train to Munich

On our arrival at Munich’s main train station (or Hauptbahnhof) we went looking for lunch.

There are many places that serve lunch at the train station, and they’re used to customers

walking in with piles of luggage. We found some Thai food for lunch and a Nutella crepe

for dessert.

Thai Curry, Munich Train Station

Nutella Stand, Munich Train Station

We’d made reservations to stay at the H+ Hotel, located in the neighborhood south of the

train station. We’d stayed in this area before, and had found it to be more affordable than

some and within walking distance of all of the transportation options to be found at the

Hauptbahnof. On the way to the H+, we noticed some changes that had happened since our last

visit. There was a much greater concentration of Middle Eastern restaurants with their

interesting but non-Germanic aromas, and the people in the area seemed to be speaking a

language that was neither German nor English. Some news stories of recent years occurred to

us – stories about a civil war being fought in Syria, with refugees looking to move to

places that were less dangerous, and stories about Germany agreeing to take in a fairly

large number of these refugees. We never found out for sure, but it seemed possible that

this may have become a neighborhood of Middle Eastern refugees. We were a little nervous,

as we weren’t sure where the neighborhood had been transplanted from, or how they felt about

Americans, but as it turned out we didn’t have any problems of that sort.

South of the Hauptbahnhof

Once we’d checked in, though, we found we had a different sort of problem – we were

running out of clean clothing. We checked online and found a laundromat that was within

walking distance, and I was sent out to reconnoiter (find the place, see what kind of

shape it was in and how crowded it was, see how the system worked, etc.) while Nella and

Connie sorted the laundry. I found the laundromat without too much trouble, and it

looked suitable – modern, clean, not too many people, clear instructions posted in

German, English and probably Arabic. I returned to the hotel and found that Nella and

Connie had sorted and suitably arranged the dirty laundry in one of our suitcases. We

all went off to the laundromat and started the wash cycle without any difficulty.

At the Laundromat

Except for boredom, that is. On the way, we’d noticed a church that looked like it might

be interesting. It turned out to be the Paulskirche (St. Paul’s Church), and we gave

it a quick visit while the laundry was in progress.

The Paulskirche is a large Catholic church that was built between 1892 and 1906 in the

neo-Gothic style. We didn’t know it at the time, but the church is located a short block

north of the Theresienwiese, where the Oktoberfest is held each year. The church

has a tall 318-foot tower at its east end and two 249-foot towers at its western end,

which are the features that attracted our attention.

Tower, St. Paul's Church

South Side of Church

A Gargoyle

North Side of Church

Statue of St. Paul

Bob and Connie and Church Door

The inside of the church in some respects looked relatively modern when compared to the exterior.

Layout of Church

Inside the Church

Baptismal Font

Organ Loft in Left Transept

(New) Main Altar

St. Joseph Altar

Church from Main Altar

Bob with Rose Window and 2017 Easter Candle

2017 Easter Candle

Pulpit

Nella Lighting a Candle

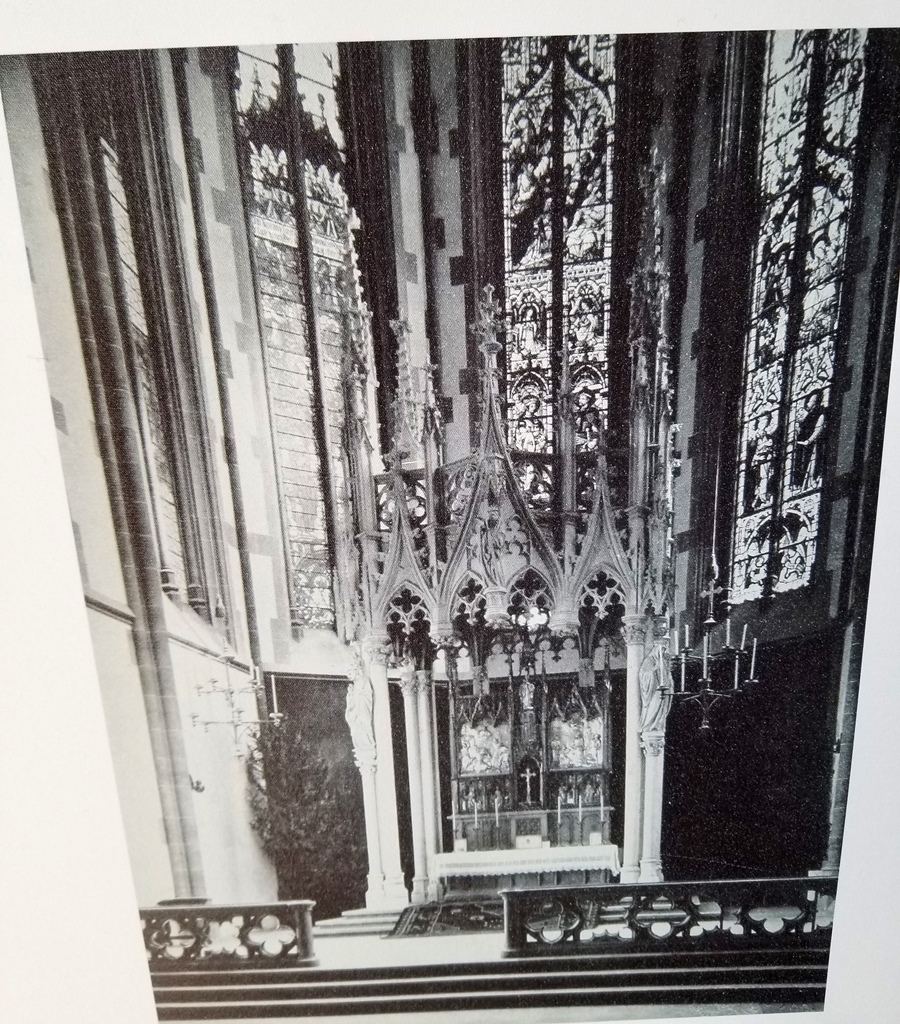

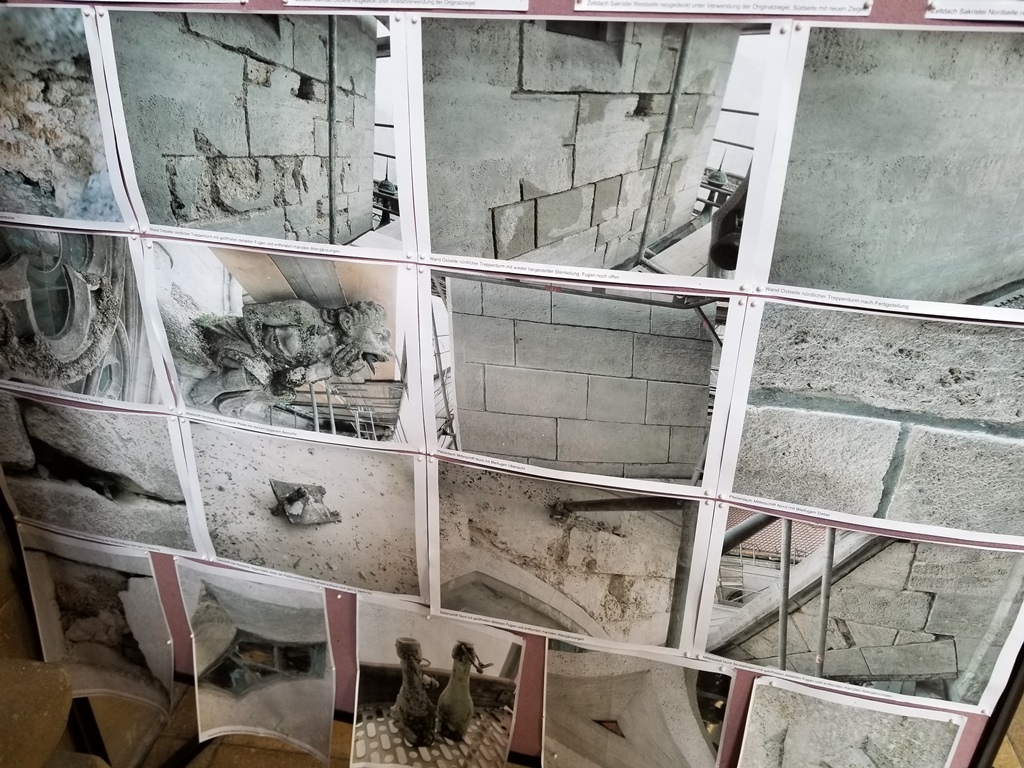

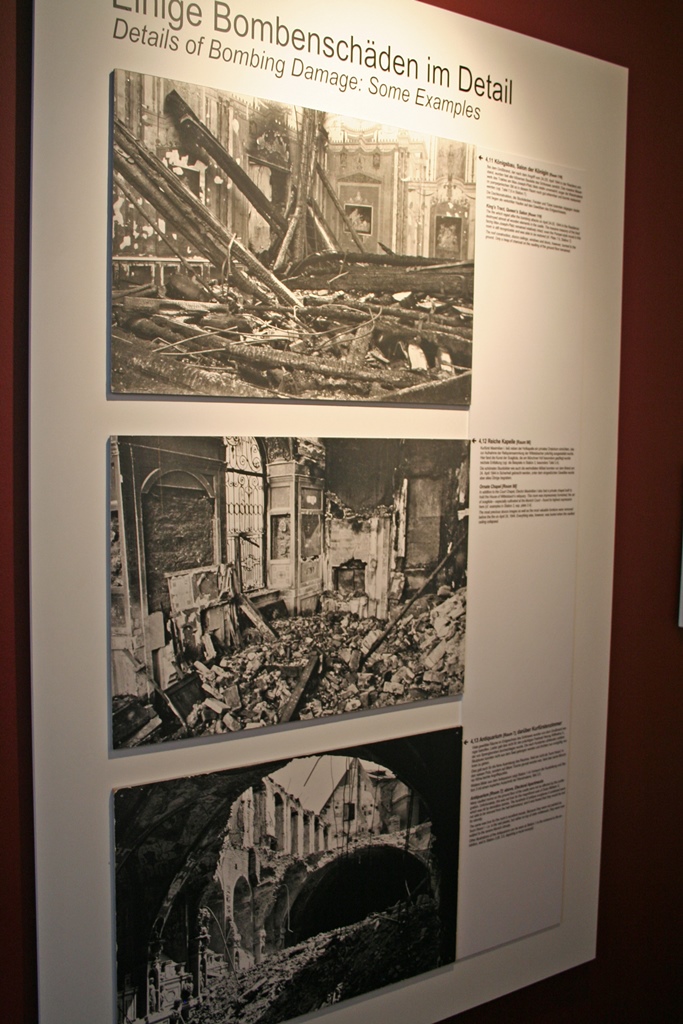

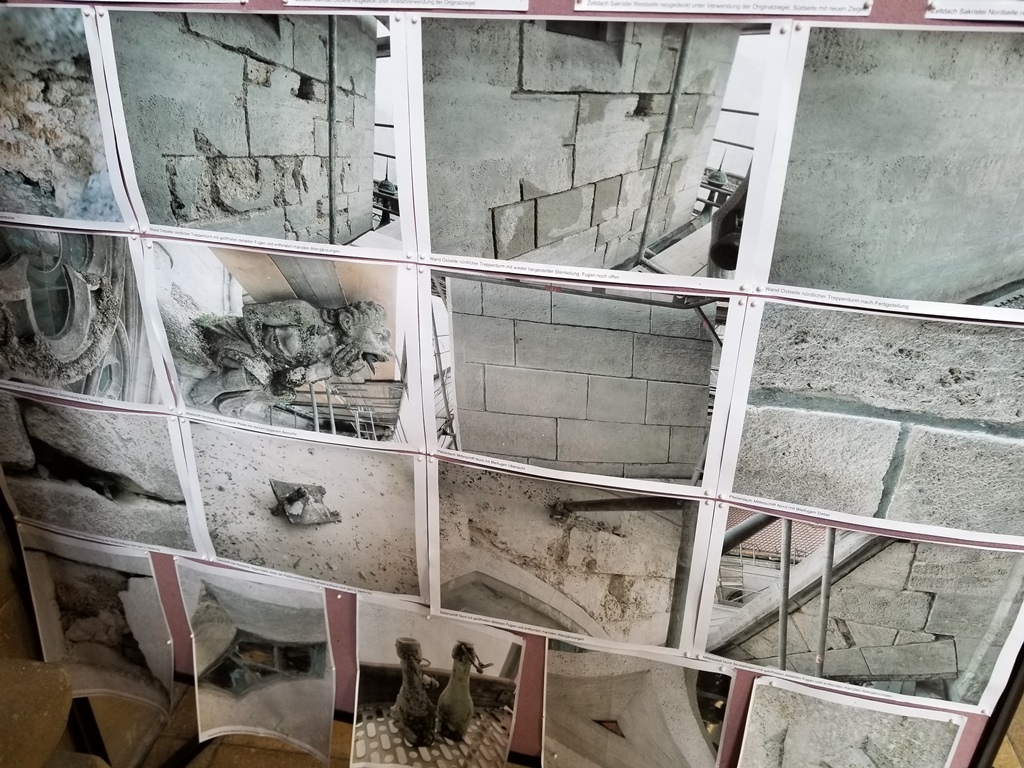

The church was badly damaged during World War II, mainly by bombing raids in October

and December of 1944. The main altar and the organ were destroyed, in addition to many

other interior furnishings and features. Much was restored in the 1950s, but in the style

of the time because of the available resources. The organ was finally replaced in 1964.

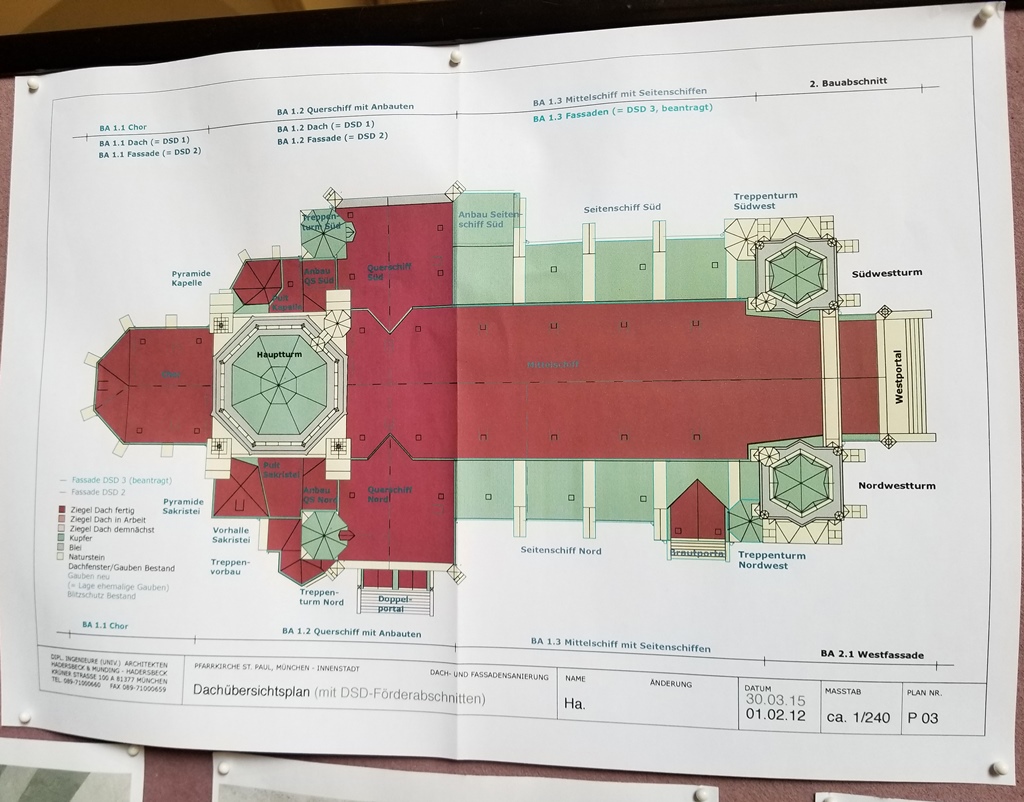

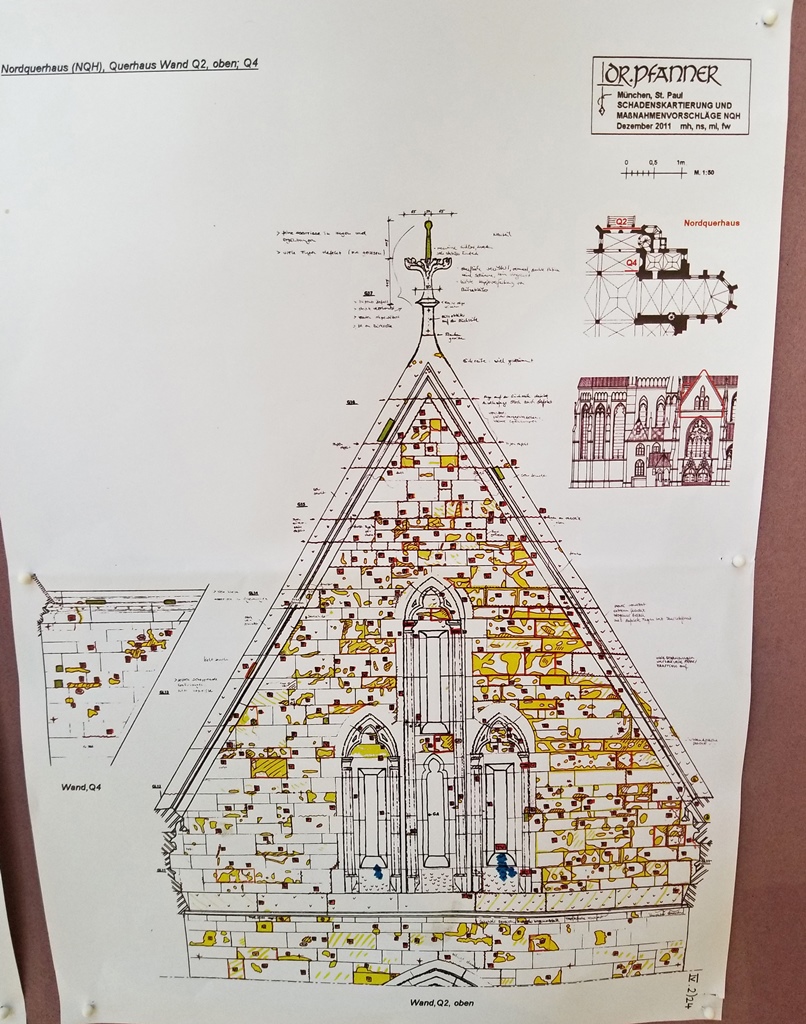

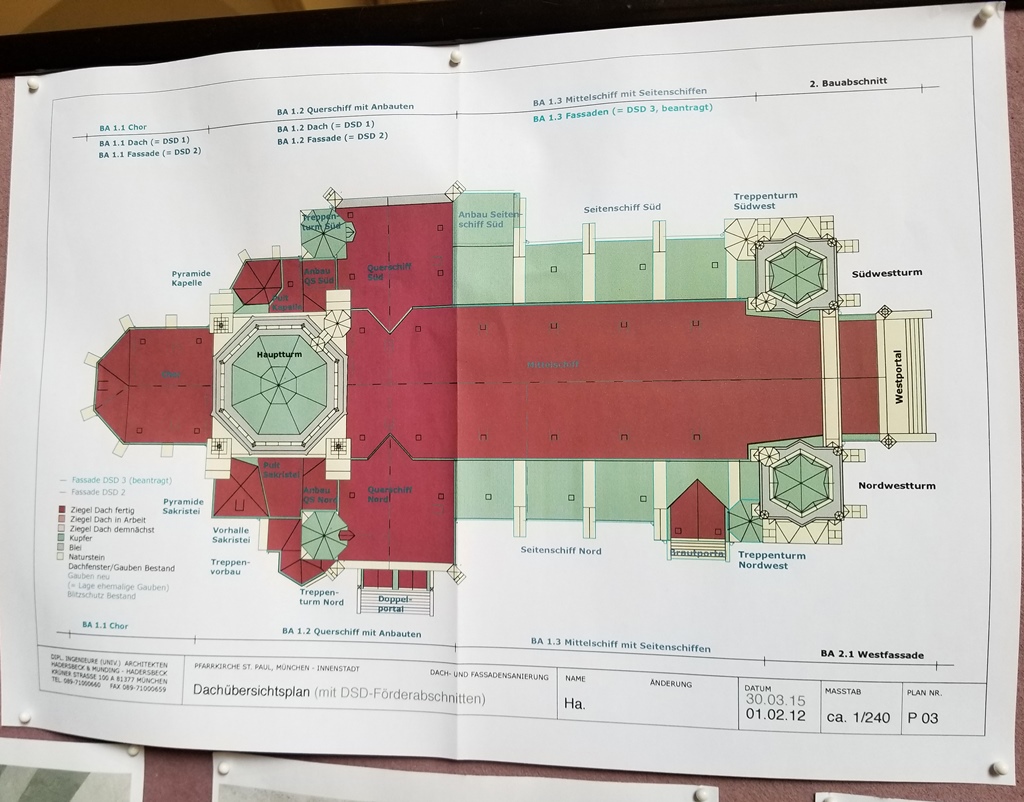

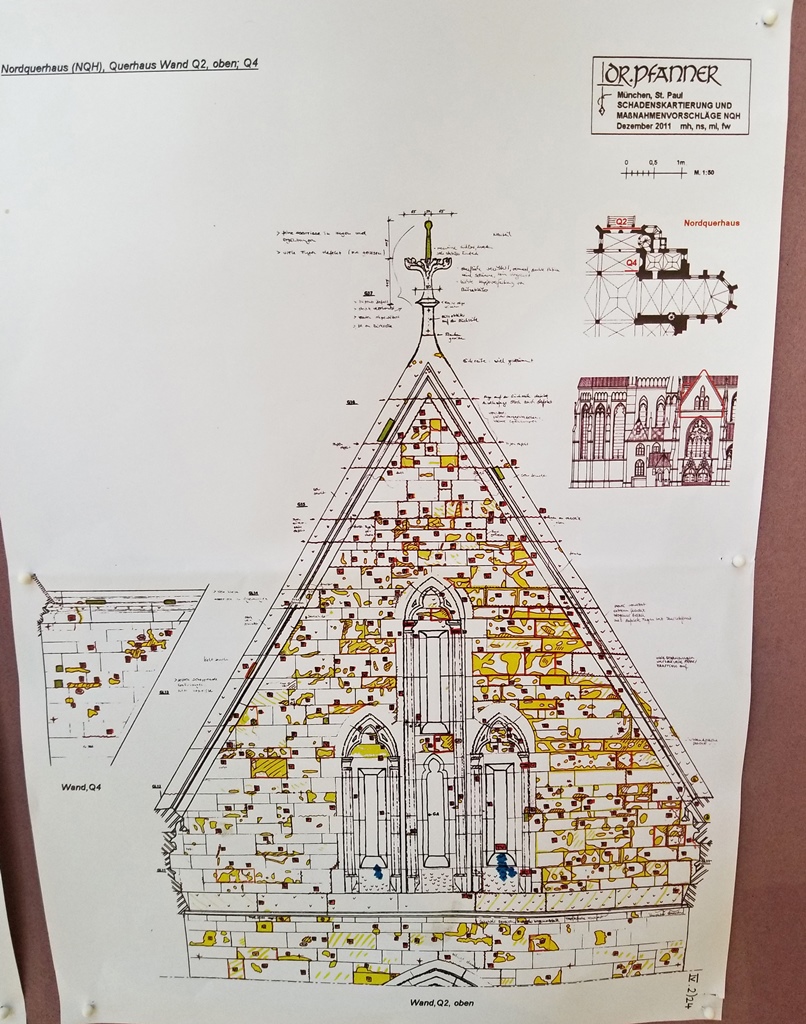

Though the church was restored enough to function as a church, much work remains to be done,

and detailed plans were posted in the church, along with a request for donations.

Bomb Damage

Original Altar

Church Features Needing Repair

Detailed Diagram of Repair Plans

After our once-over of the church, we returned to the laundromat and submitted our

clean-but-wet clothes to the drying process, which also finished successfully. We

dragged it all back to the hotel and took a break until we got hungry for dinner.

The main tourist attraction of Munich (when Oktoberfest isn’t going on) is the Old Town,

or Altstadt, which also has several restaurants. Our hotel wasn’t in the Altstadt,

but was in walking distance. We didn’t feel like doing that much walking, so we walked

the shorter distance to the train station, where we found the subway, or U-Bahn

(Untergrundbahn), which took us to the center of the Old Town. Other public

transportation options include the commuter train, or S-Bahn (Stadtschnellbahn),

buses and a number of trams. For our purposes, the U-Bahn was perfect, however.

After a couple of stops, we got off the U-Bahn and popped up in the Marienplatz

(marine-platz, or Mary’s Square), in the middle of the Altstadt. The Marienplatz is

dominated by the Neues Rathaus, or New Town Hall (it’s not really all that new,

but it’s not as old as it looks either; more on the Marienplatz and surrounding buildings

in a future page).

The Munich Altstadt

Bob and Neues Rathaus, Marienplatz

Neues Rathaus, Marienplatz

Bob and Nella and Neues Rathaus

Sticking to our pattern of not eating German food in Munich, we found dinner at a

Japanese restaurant.

Japanese Food for Dinner

Near the Marienplatz we found another square, the Frauenplatz, largely occupied

by the symbol for the city, the tall, twin-towered cathedral known as the Frauenkirche

(Cathedral of Our Lady; more on this church in a future page). In front of the church there

is an interesting fountain called the Wasserpilz Brunnen, or Water Mushroom Fountain,

which was installed in 1972.

Frauenkirche

Wasserpilz Brunnen

The main pedestrian thoroughfare in the Altstadt is a street called the Kaufingerstraße

and the Neuhauser Straße. The street has two names because the name changes halfway

between the Marienplatz and the boundary of the Altstadt. At the spot where this name change

occurs, there is a museum called the German Hunting and Fishing Museum. We’ve never actually

visited this museum, but in front of it there are some bronze sculptures it’s impossible to

avoid taking pictures of.

Bob and Connie and Bronze Boar

Giant Bronze Catfish

Before Kaufingerstraße/Neuhauser Straße was pedestrianized in 1972, it was one of the

most traffic-congested streets in the city. When the cars and trams were routed

elsewhere, the local merchants complained that they would lose customers. The complaints

didn’t last long, however – it turns out that pedestrians do a lot more shopping than

people stuck in traffic. And a lot of pedestrians take this route. Including us. But

on this particular evening, the stores were closed because it was past 9, so all we could

do was window shop. But we would be back.

Mugs and Nutrackers in Store Window

Mugs

Cuckoo Clocks

Oberpollinger Department Store

The pedestrianization ended at a square called Karlsplatz, beyond which there was

an extremely busy roadway. On the other side of the roadway we could see the grand old

Palace of Justice, or Justizpalast.

Justizpalast

It’s possible to cross the street from this point (it’s actually a divided roadway, so

two crossings are necessary) using crosswalks, but it’s also possible to get out of the

traffic (and weather, if it’s bad) by going through an underground shopping mall which

eventually connects to the train station. We took the shopping mall route and eventually

passed through the station on our way back to our hotel. But we would be spending a lot

of time in the Altstadt on this trip, and our first stop the next day would be the

hyper-Baroque Asamkirche.