Stephansdom

Vienna's St. Stephen's Cathedral,

or Stephansdom, is the mother church of

the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna. It is also the symbol of the city and its

most-visited tourist attraction, with nearly three million visitors per year. It's

iconic enough that the Josef Manner company contributed to one of the cathedral's

restoration projects in return for the rights to use a small picture of the cathedral

on the packaging for its wafers (you can find these in the U.S. at import

stores – they're quite tasty).

Manner Wafers

The cathedral is in fact impossible for a tourist of any ambition to ignore, being

located in the center of the old town and being the most massive thing in the

vicinity. The cathedral also has many distinctive features, the two most obvious

probably being its 448-foot-tall gothic tower and its intricately-tiled roof. Most

of the roof has a multicolored zig-zag pattern, but a smaller section above the

main altar depicts Austrian coats of arms.

South Tower

South Tower

Coat of Arms on Roof

The cathedral is located in the middle of an open space called the Stephansplatz,

which is a natural place for people to accumulate – it's in the center of the old town,

both geographically and spiritually. This situation is exploited by salespeople of all

stripes. The square and its surroundings are a major shopping area, with many high- and

medium-end stores (though not much in the way of bargain places). Political evangelists

wield signs attempting to sway people to their way of thinking (or at least to get the

word out that they're more virtuous than you are). A queue of carriages waits on the

far side of the cathedral to take passengers on atmospheric (with a bit of eau de

horse) tours of the old town. And a gauntlet of vendors wearing baroque clothing

(and sometimes wigs and occasionally sandwich boards) sells tickets to classical music

concerts.

Stephansplatz

Concert Vendors Outside West Portal

Carriages North of Cathedral

Adding to the crowd, the square is also on top of a major U-Bahn station, where two

lines of the subway intersect. Nella and I crawled up out of this station,

oriented ourselves (the cathedral is pretty easy to locate), and headed for the

entrance. We had to dodge a few ticket vendors, but eventually we reached the

doorway, found in the western end of the church.

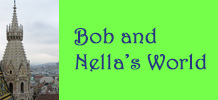

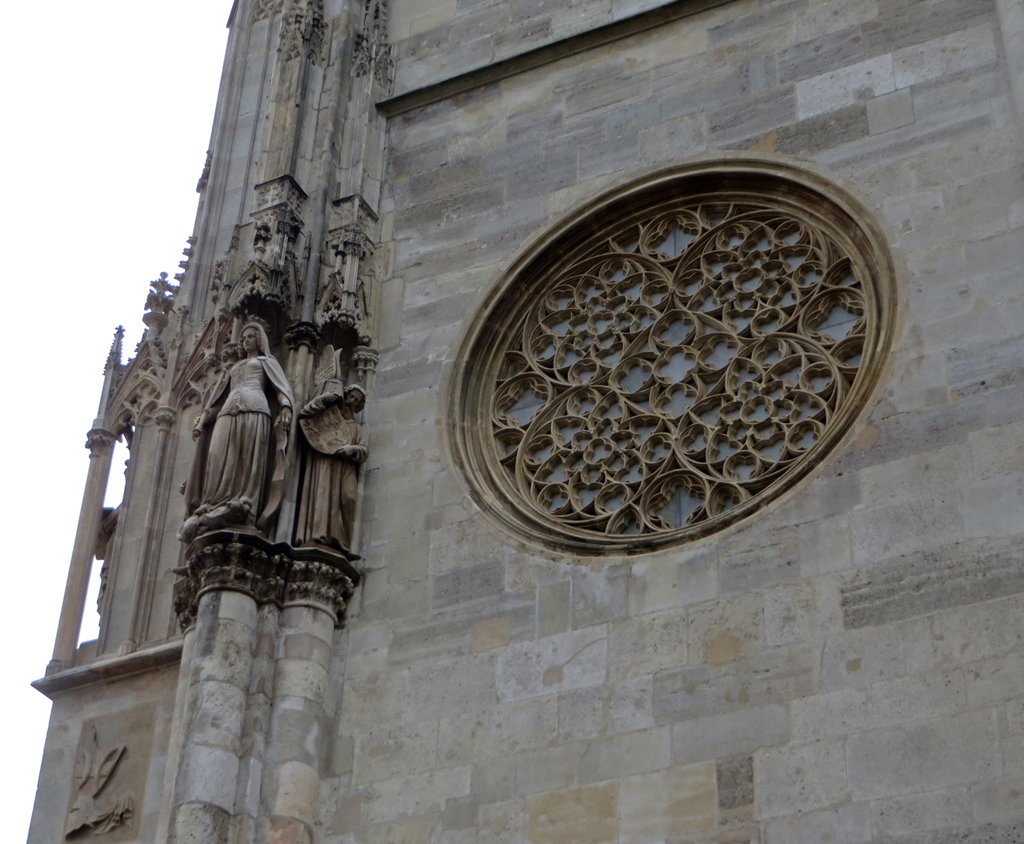

Western Façade

Katherina von Luxemburg Statue and Rosette Window

The western façade and towers are the oldest part of the cathedral, constructed as

part of a Romanesque church built in the 13th Century. In the 14th Century, a choir

was added to the east end of the church, in the newly fashionable Gothic style. The

choir was built to be as wide as the church's transept, making it wider than the rest

of the church. After the choir's completion, it was decided to widen the narrow part

of the church (also in the Gothic style) to match the choir. In order to avoid

disrupting services any more than necessary, the Gothic walls were built outside the

old Romanesque walls as services continued. After the outer walls were completed

(early in the 15th Century), the Romanesque walls were disassembled. At this time

the roof was added, being built with a steep incline to prevent accumulation of snow,

and with an internal wooden support structure that would last 500 years. Vaulting

and other work on the inside of the cathedral continued until 1511, when major

construction work came to an end. One consequence of this work sequence was a

mismatch of the cathedral's towers. The Gothic south tower of the cathedral (the

448-foot spire that survives today) was completed in 1433, and work began on a

matching north tower in 1450. But by 1511, the Renaissance was underway, and Gothic

was judged to be so 15th Century, so construction was halted. Later, a

Renaissance-style "cap" was added to the north tower (by this time about half the

height of the south tower), and the builders called it a day.

During most of this, the Stephansdom was not a cathedral. Vienna was part of the

Diocese of Passau, and St. Stephen's was considered to be a parish church. The

Viennese were not happy with this situation, and for many years asked succeeding

popes whether they could please have their own diocese. They were always turned

down, however, because of resistance from the Bishops of Passau. But this changed

in 1469, when Frederick III, the first Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, was able to get

agreement from Pope Paul II to form the Diocese of Vienna. And later, in 1722,

Charles VI was able to get Vienna a promotion to archdiocese from Pope Innocent

XIII.

Over the centuries, the Stephansdom supplied services to the famous of Austria,

including weddings (e.g. Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) and funerals (e.g.

Mozart, Antonio Vivaldi, Franz Joseph I, Kurt Waldheim). The cathedral has also

been a burial place, for the aforementioned Frederick III and for Prince Eugene of

Savoy (a great general who successfully led Habsburg armies for many years in the

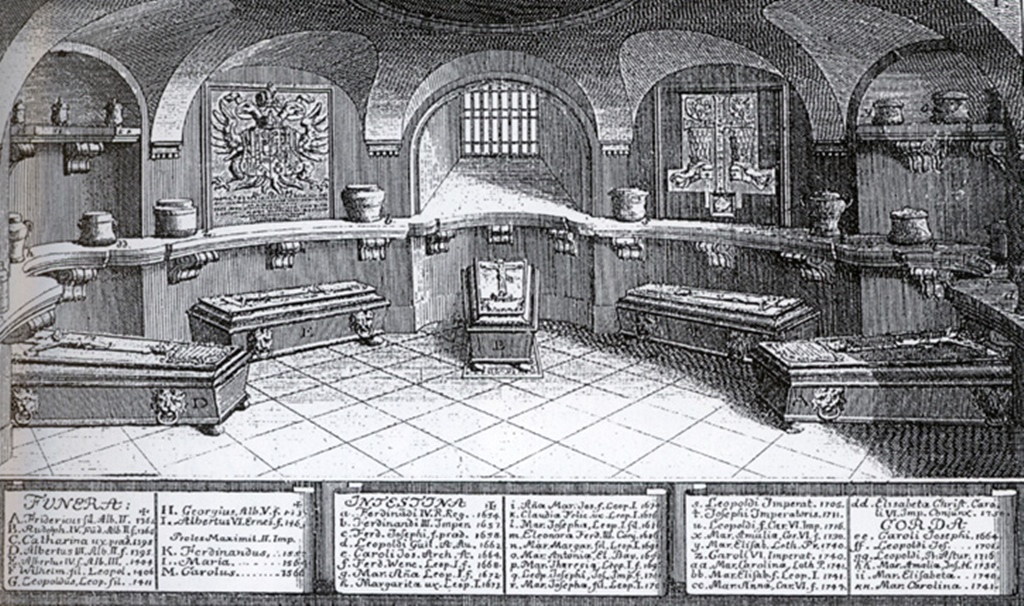

17th and 18th Centuries), among others, who have their own tombs. In addition,

many are buried in the Cathedral's crypt, some in coffins, and many who were

tossed into pits in the crypt during a plague epidemic in 1735 and at other times

(apparently there are the remains of thousands, many in piles of nicely-stacked

bones). An occasional burial (e.g. of a deceased archbishop) still occurs in the

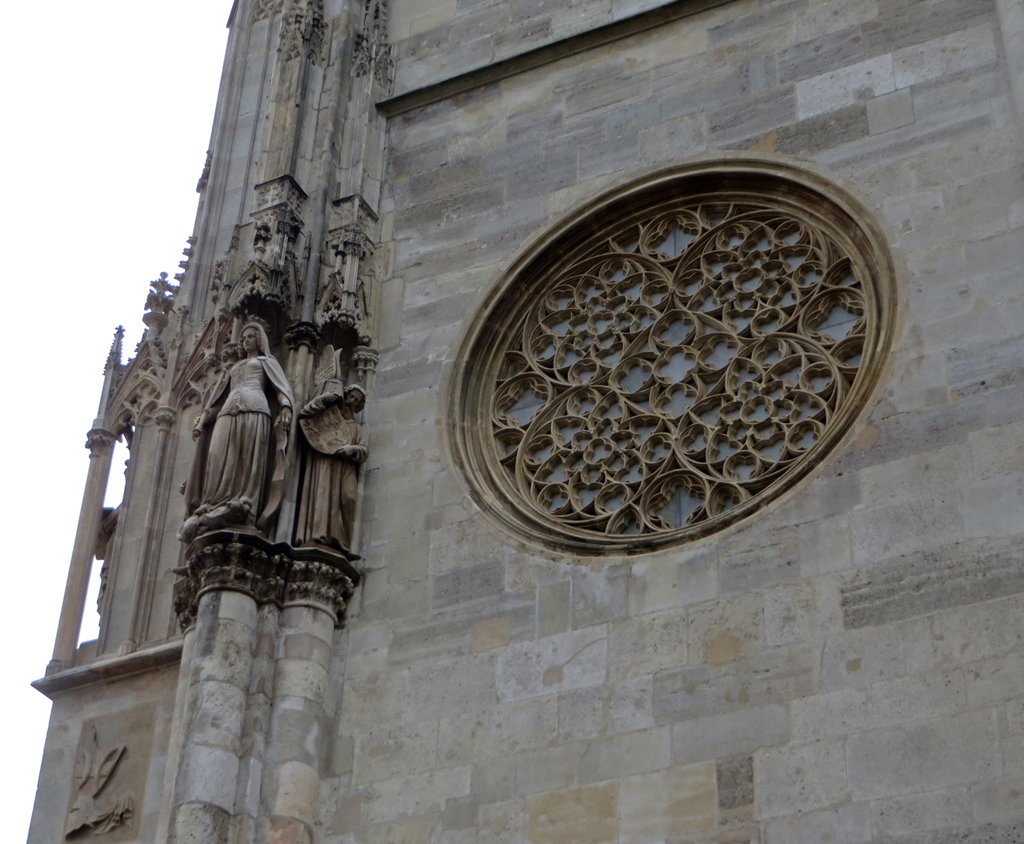

crypt. And in keeping with the Habsburg tradition of burying bits and pieces of

people in different places, there are more than 60 jars in the special ducal crypt

containing royal hearts and entrails. The gruesome-minded of you might be asking

yourself, "What would happen if one of these jars were to become unsealed?" You

don't really need to imagine this – the details are sketchy (one envisages a

member of the custodial staff being careless with a vacuum cleaner), but

apparently this very thing happened, not long ago. The result was a smell that

was so beyond description that no one could be persuaded to go down and fix it for

a day or two.

Ducal Crypt

But to continue with the history of the cathedral (and possibly regain some composure),

the Stephansdom was to stand, without major damage, until World War II. Toward the end

of the war, much of the city was targeted by Allied bombing, but not the cathedral.

As the Nazis retreated in the waning days of the war, there were orders to destroy the

cathedral on the way out (Nazis being Nazis, I guess). But the orders were disobeyed

by a German captain who thought this would be a horrible thing to do. So the

Stephansdom escaped typical forms of military destruction. Instead, it was damaged on

April 12, 1945 by a fire that had been started by looters in surrounding buildings.

This fire spread to the roof of the cathedral, causing its 500-year-old wooden support

structure (and the roof it was holding up) to collapse. Fortunately, the possibility

of some sort of collapse had been anticipated, and many of the immovable works of art

in the cathedral (some appearing below) were protected by brick structures that had

been built around them. But some damage unfortunately could not be prevented – notably,

a set of beautifully-carved 1487 choir stalls was lost.

Cathedral Without Roof

Reconstruction work on the cathedral started almost immediately. There was a limited

reopening in 1948, and a full reopening in 1952. The new roof was completed (with

a steel support structure) in 1950, a year commemorated in the tiles surrounding one

of the new coat-of-arms sections. Since the 50's the cathedral (particularly the

south tower) has continually been undergoing restoration work – there was some

scaffolding on the building's south side during our visit, but it was not intrusive

to our appreciation of the building.

Entry to the church is free, but most of the interior is only accessible to those who

buy tickets. There is a fence near the back of the church you can see through, but

full exploration of the church requires a ticket. Apparently most visitors do not

buy tickets, and are content to look through the fence, but we paid for admission and

found it to be well worth the price. There is a small ticket counter at the left end

of the fence, and there are different packages you can buy. We bought tickets that

included admission to the church, the Treasury and the north tower, along with

audioguides. There was much to see, and the requirement to buy tickets had the

welcome effect of reducing the crowd size to a level much more manageable than the

crush of people peering through the fence.

Once past the ticket counter, visitors are allowed to wander around the cathedral at

will and to photograph whatever looks interesting to them. Generally speaking, the

interior is on the dim side, but it's not difficult to get decent pictures of most

things. We first headed for the main focus of the church, this being the high altar

in the front. At 351 feet, the church is longer than a football field, so this was

something of a walk, but we planned on going to the front first and working our way

back. The main altar dates back to 1647, and the large painting on it depicts St.

Stephen being stoned to death outside the walls of Jerusalem. Not the most cheerful

subject, but probably unavoidable, given the name of the church. At the top of the

altarpiece is a statue of the Virgin Mary, and just below her is a small painting,

also of the Virgin Mary. The stained glass windows behind the altar are the only

surviving originals in the church.

Inside the Cathedral

Main Altar

Top of Main Altar

The Stephansdom has three naves. The one to the left of the central nave is

devoted to the Holy Mother (also called the Women's Nave), and the one to the

right is dedicated to the apostles. At the head of the Women’s Nave, to the

left of the high altar is the 1447 Wiener Neustädter Altar, which

depicts scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary. It was apparently

constructed using elements that were even older, and is thought to have been

constructed at the request of Frederick III. Frederick had a sort of

"trademark" he liked to have stamped onto various creations for which he was

responsible, this being the letters "A.E.I.O.U.", and these letters can be

found repeated twice in the detailed photo below, above the center "windows"

at the bottom of the altarpiece (the U looks like a V – this was the style).

Nobody is quite sure what the "A.E.I.O.U." is supposed to have stood for,

besides the obvious collection of vowels. The altar is named for the city of

Wiener Neustadt, from whose monastery it was acquired in 1884. To the right

of the altar there is an apparent marble tomb belonging to Duke Rudolf IV,

who died in 1365. But the duke and his wife are actually buried in the Ducal

Crypt, and the marble behemoth is a cenotaph.

Wiener Neustädter Altar (1447)

Wiener Neustädter Altar (detail)

Cenotaph of Rudolf IV

At the head of the Apostles' Nave, on the other side of the high altar, is an

actual tomb. This one is occupied by Frederick III himself. The tomb is sculpted

from red marble and is considered a masterpiece of late Middle Age sculpture. It

is covered with 240 sculptures, including many of small creatures, and was

sculpted over a period of 45 years, beginning 25 years before Frederick's death.

Also near the head of the Apostles' Nave is the choir organ, which, despite being

built relatively recently, is mechanically operated.

Tomb of Frederick III

Tomb of Frederick III

Choir Organ (1991)

From the Apostles' Nave, we headed toward the back of the church, as we wanted

to get a closer look at the cathedral's pulpit, located not far from the ticket

counter (it was built toward the back so more people could hear). Again, the

pulpit is considered a sculptural masterpiece of its period, which pretty much

coincided with that of Frederick III's tomb. In fact, recent thinking credits

it to the same artist, Nikolaus Gerhaert van Leyden, though there seems to be

some doubt about this (it was long thought to be the work of a sculptor named

Anton Pilgram). Depicted around the outside of the pulpit are the four original

Doctors of the Church (St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Ambrose, St. Gregory the Great

and St. Jerome), and the handrail of the staircase leading up to the pulpit is

decorated with small renderings of toads and lizards. Underneath the pulpit is

what appears to be a self-portrait of the sculptor, looking out of a window.

This unsigned self-portrait is fondly known as the Fenstergucker (window

gawker).

Bob Photographing Church

Central Nave

Pulpit

Pulpit

Pulpit Platform

The Fenstergucker

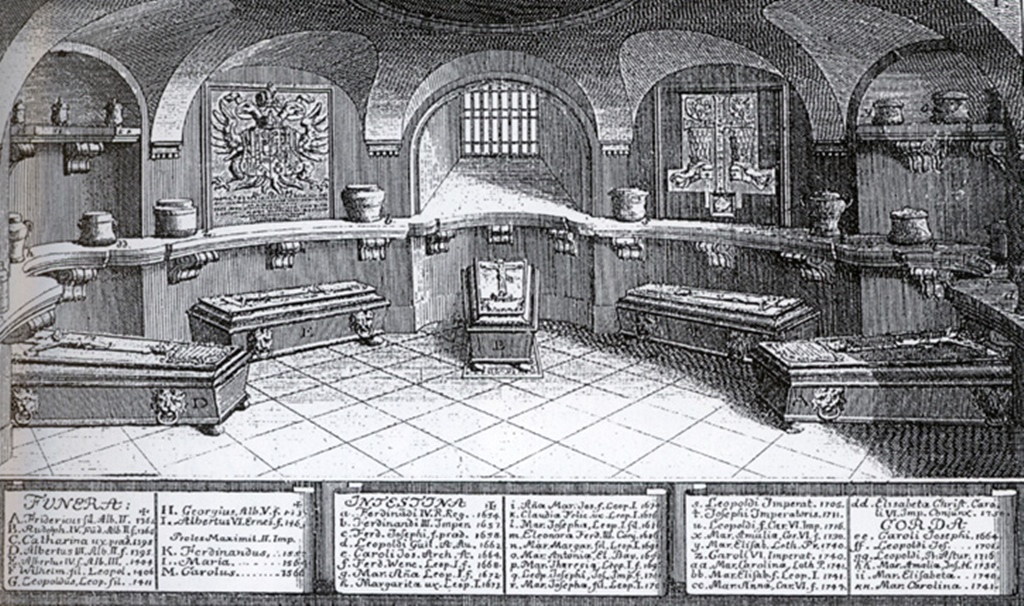

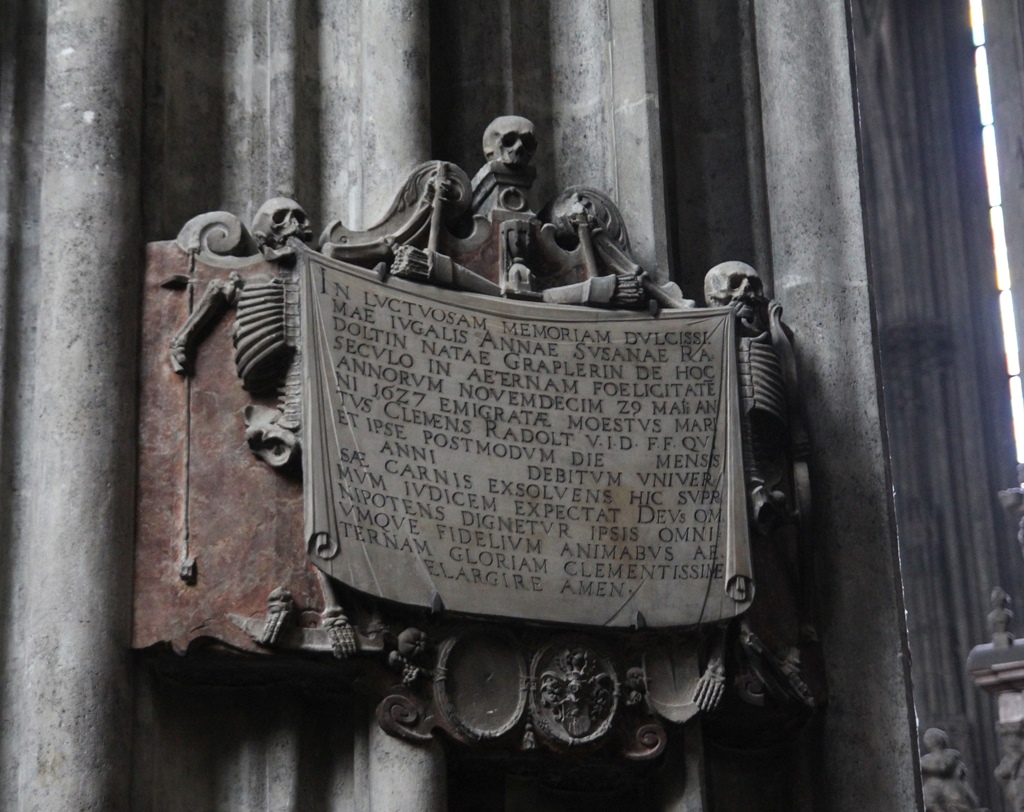

From the pulpit we walked through the naves, looking at the many altars and memorials

displayed. Some are along the outside walls of the cathedral, and some are attached

to the columns between the naves.

St. John the Baptist's Altar

St. Joseph Altar

"Old Woman" Altar (1693)

Trinity and St. Sebastian Altars

St. Januarius Altar

Statue of St. Anthony

St. Catherine Altar (1701)

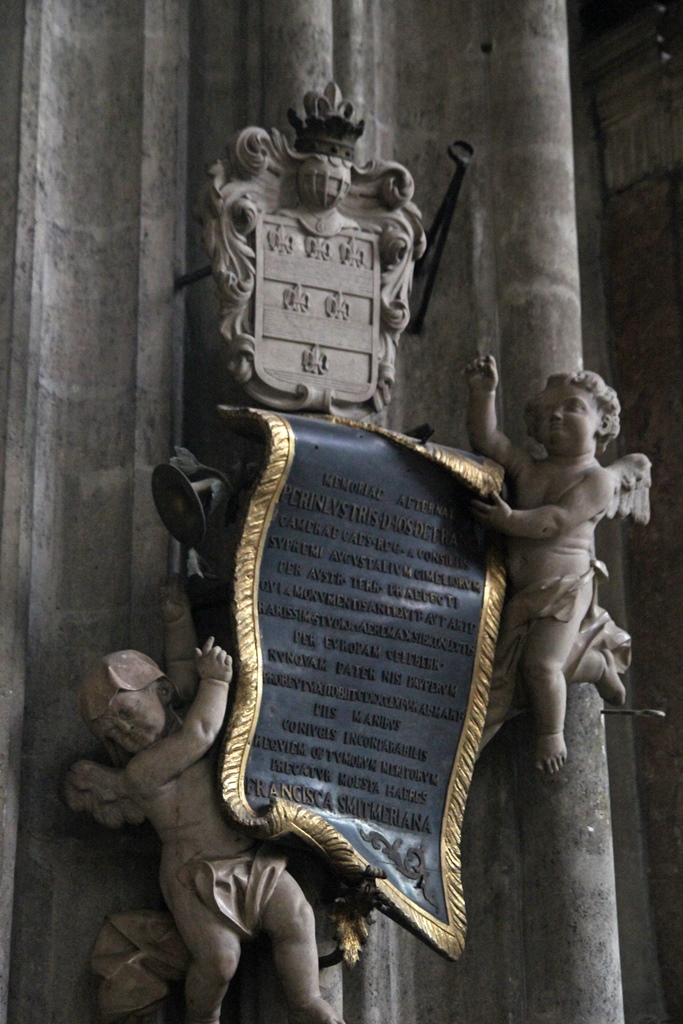

Memorial to Francisca Smitmeriana

Memorial Scroll

Part way down the Apostles' Nave there is an exit, in the base of the south

tower. But before getting to the door, there is another door to the left,

through which you can see into a small chapel known as St. Catherine's Chapel.

This is the baptismal chapel for the cathedral. In addition to an altar, this

chapel holds a baptismal font and a cover for it, both elaborately carved and

both from 1481.

Altar, St. Catherine's Chapel

Baptismal Font (1481)

Baptismal Font Cover (1481)

It's possible to walk part way up the south tower (no elevator), but you

need to have a ticket for it. Instead, we purchased tickets for the north

tower, which does have an elevator, so we headed for the elevator entrance,

off the Women's Nave. Even though the north tower is much shorter than the

south tower (223 feet vs. 448 feet), it seems quite tall when looking down

from the top and it does offer a fine view of the northern half of Vienna.

But looking south, you instead have a fine view of the cathedral's roof.

Cathedral North Tower

View West from North Tower

Roof from North Tower

Roof and Romanesque Tower

Stephansplatz from North Tower

Votivkirche from North Tower

Nella on North Tower

Rooves of Cathedral and Eastern Old Town

Chicken on top of Roof

South Tower from North Tower

View North from North Tower

Jesuitenkirche from North Tower

Nella on North Tower

Toward the north there is an amusement park called the Prater, and from

the north tower it's possible to see a Ferris wheel, known as the Riesenrad,

located at the entrance to this park. The Riesenrad was built in 1897 to celebrate

Franz Joseph's Golden Jubilee as emperor. At 212 feet tall, the Riesenrad was

quite tall for its time, but other Ferris wheels in Europe and the U.S. were taller.

But over time these other wheels were demolished (there was also a plan to demolish

the Riesenrad in 1916, but it proved to be too expensive), and by surviving, the

Riesenrad became the tallest Ferris wheel in the world in 1920, retaining that

status until 1985, when the Technostar wheel (279 feet) was unveiled in Japan. The

Riesenrad played a memorable part in the post-war movie The Third Man, when

a creepy Orson Welles looked down from it and remarked that the people below were

like "little dots", and that it would be insignificant if one of them "stopped

moving, forever".

Riesenrad from North Tower

The Riesenrad

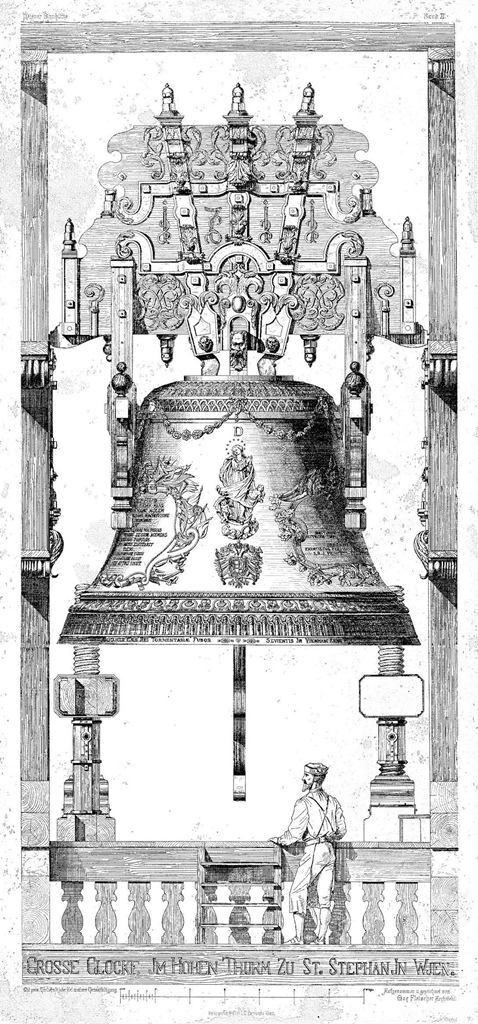

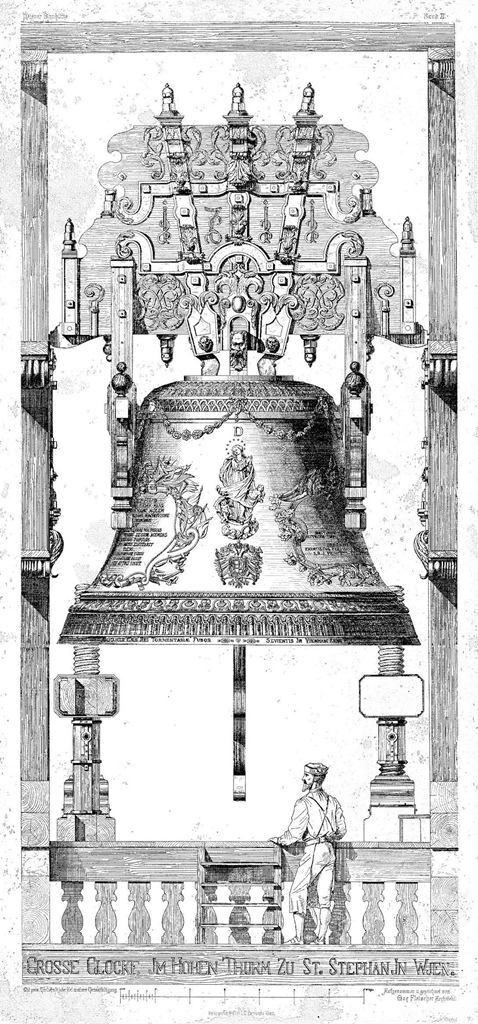

Another interesting sight from the north tower is much closer, this being a large

bell on the tower itself, called the Pummerin ("Boomer"). The Pummerin was

originally cast in 1705, using metal from Turkish cannons captured in the 1683

Siege of Vienna. The original bell was destroyed in 1945 in the fire that also

destroyed the cathedral's roof. It was recast in 1951 using metal from the

original bell, plus some additional metal from a few surviving Turkish cannons

that had been kept in a military museum. The new bell weighs more than 44,000

pounds, and is the third largest in Europe, after bells in Cologne, Germany and

Rovereto, Italy. It is only rung on high Catholic holidays and New Years' Day,

plus on days of state funerals.

The Pummerin

Bell Plaque, North Tower

Returning back down the elevator into the church, we headed for the Treasury,

reached via a stairway up to the gallery at the west end of the cathedral.

The Treasury was filled with beautiful, valuable and historical items, but

the first thing we noticed was the bird's-eye view of the entire church that

we could see from the balcony.

Apostles' Nave

Church from Base of Apostles' Nave

Central Nave

Women's Nave

Turning around to examine the Treasury items, we were first confronted by

gigantic organ pipes at close quarters, and were very thankful that nobody

was playing anything. The main organ of the cathedral was installed in

1960, financed by public donations to replace the old organ, which did not

survive the war. We also quickly came across the keyboard, which looked

complicated.

Organ Pipes

Organ Controls

We finally made our way to the Treasury, much of which is behind the organ

pipes. As is common among cathedral treasuries, many of the items on display

were either relics or containers for relics.

Fragment from Tablecloth of Last Supper

Reliquary of St. Leopold (1588)

Reliquaries

Maria Pòcs Monstrance

Sunburst Monstrance (1658)

Monstrance of the Nine Choirs of Angels (18th C.)

Monstrance for Feast Days (1754)

Another item in the Treasury was a painting known as the Maria Pòcs Icon. This

icon was painted in 1676 and was displayed in the church in the town of Pòcs in

Hungary. In 1696 the painting was reputed to have miraculous properties, with the

Virgin in the painting seen on occasion to be crying real tears. Emperor Leopold I

though the icon might be in danger in Hungary, as Turkish armies still controlled

much of the country, so he had it brought to the Stephansdom in 1697 for its

protection. The crying has not happened since, though a number of other

miraculous occurrences have been attributed to the painting. Eventually the

people of Pòcs wanted their icon back, but the emperor sent them a copy instead.

The people weren't happy at first, but the copy was soon seen to exhibit tears

and other miraculous properties, so they were happy enough. Back in Vienna, a

number of frames have been created for the icon, including a frame called the

Rosa Mystica, created on its arrival. This was the frame we saw in the

Treasury.

Maria Pòcs Icon with Rosa Mystica Frame

We also found other artworks in the Treasury, of differing types. One of them,

the Hutstocker grave monument, was created in 1523 but was largely destroyed in

1945. Some of the fragments have been reassembled for display.

St. Stephen's Cope of the Eleonora Vestments (1697)

Gothic Panel Paintings (ca. 1390)

Descent from the Cross (ca. 1320-30)

Pietà (early 16th C.)

Fragment of the Hutstocker Carrying of the Cross (1523)

After finishing with the Treasury, we returned to our hotel to rest. As usual,

we had ambitious plans for the following day. These included a day trip

upriver, to visit the town of Melk.