Note: A YouTube companion video for this page can be found

here.

Budapest's Metro is the second-oldest electrically-operated underground railway in the

world (the London Underground is the oldest). Three of its four lines opened in the

years since 1970, but its original line started operations in 1896. This line, now

known as Line 1, includes one station very near to St. István's Basilica, and another

very close to Budapest's Museum of Fine Arts. While the line's cars have been updated

since 1896, they couldn't be considered state-of-the-art, but they were more than

adequate to the task of efficiently conveying us between these two stations.

The Metro station near the Fine Art Museum is called Hosök tere, a name having

nothing to do with museums or art. It translates as "Heroes' Square", referring to a

large open area next to the museum filled with monuments and statues.

Heroes Square

Another Angle

Construction of the structures and figures in Heroes' Square was begun in 1896 to

celebrate the thousandth anniversary of the Magyar conquest of the region. The

principal structures within the square are a central column, a large rectangular

cenotaph in front of it, and two curved colonnades behind it. The cenotaph is

sometimes mistakenly referred to as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, but nobody is

buried there – it's a memorial to Hungarian heroes in general. At the top of the

column is the Archangel Gabriel, holding the Hungarian crown and an apostolic

double-cross. Bunched around the base of the column are figures of the seven

Magyar chieftains most instrumental in the conquest of the area. For the record,

these chieftains were Elod, Ond, Kond, Árpád, Tas, Huba and Töhötöm, with Árpád

(in the middle) considered to have been the most important.

Column and Cenotaph to Memory of Heroes

Bob and Base of Column

Magyar Chieftains

Chieftain Huba

Chieftains Elod and Ond

Not much is known about the seven chieftains, so most of the details in their

statues come from the imagination of the sculptor. Chieftain Huba's depiction looks

particularly interesting, with antlers having been attached to his horse's face.

This was no doubt intended to be fearsome, and in an actual battle maybe it would

have been, but I can’t help but be reminded of the hapless dog/reindeer in the

classic cartoon of the Grinch and Christmas.

The matching colonnades behind the column each depict seven figures from Hungarian

history, above reliefs that show them doing whatever made them great. The colonnade

on the left originally had statues of figures from the Habsburg dynasty, as it was

built when Hungary was part of Austria-Hungary. However, after the colonnade was

damaged during World War II, these figures were replaced with figures of Hungarian

kings. On top of the colonnades there are allegorical figures of chariot-driving

figures representing war and peace.

Right-Hand Colonnade

Peace Statue in Chariot

Man in Chariot with Snake

Nella in Heroes Square

On the right (southeast) side of Heroes' Square is the Kunsthalle Budapest, a

neoclassical building which houses temporary exhibitions of contemporary art,

and which has no permanent collection of its own. This isn't what we'd come

here for. Instead, we were interested in the building across from it, on the

left (northwest) side of the square, the Museum of Fine Arts.

Kunsthalle Budapest

Museum of Fine Arts

The Museum of Fine Arts first opened

in 1906, and was created to establish a place for the merging of multiple collections

which were distributed throughout the city. The museum houses an impressive collection

of antiquities, as well as a collection of paintings and sculpture ranging from the

Middle Ages through the 19th Century. Or rather it would house these collections if it

were not undergoing an extensive renovation. At the time of our visit in 2014, we were

able to see the collections, but the museum closed for the renovation in February

of 2015, and is not expected to reopen until autumn of 2018. In the meantime,

some of its works are on display at the Hungarian National Gallery in Buda Castle.

Below is some of what we saw. First, a few antiquities:

Campanian Terracotta Antefixes (ca. 525-475 B.C.)

Assorted Heads (Asia Minor, 1st-2nd C.)

Marble Relief, Battle of Actium (Roman, 31 B.C.)

Jewelry of the Roman Imperial Age (1st-4th C. A.D.)

Here are a couple of pre-Renaissance works:

Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Spanish Master (14th C.)

Triptych, Taddeo di Bartolo (1395)

Early in the Renaissance, painted subjects were becoming less two-dimensional:

Death of the Virgin, Hans Holbein the Elder (ca. 1491)

The Holy Family, Master of the St. Bartholomew Altarpiece (ca. 1485-1510)

Here are some more Renaissance works. Around this time, artwork subject matter

was starting to deviate from the strictly religious. The bronze of the Horse

with Mounted Warrior was judged in 1916 to be a work by Leonardo da Vinci, and

it is believed to depict King Francis I of France (though consensus is weaker

on this). Due to its lack of finish, it's believed to be a model for a (probably

larger) planned work which was never completed.

Rearing Horse and Mounted Warrior, Leonardo da Vinci (16th C.)

Portrait of a Young Man, Albrecht Dürer (ca. 1500-10)

The Death of the Virgin, Sculptor from Allgäu (1500-10)

Winged Altar, Jörg Lederer (ca. 1515)

There are a number of works by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a German Renaissance

painter who was an early advocate of the Christian Reformation movement, and

who was in fact a close friend of Martin Luther. The paintings of ill-matched

couples show two sides of the same coin, with the more attractive members of

each couple being mainly interested in the wealth of the less attractive ones.

Fortunately, people have outgrown this sort of behavior in the centuries since

the Renaissance.

The Ill-Matched Couple, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1520-22)

The Ill-Matched Couple, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1522)

The Lamentation of Christ, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1515-20)

Salome and Head of St. John the Baptist, Lucas Cranach the Elder (ca. 1530)

Artistic technique continued to evolve through the rest of the 16th Century,

both in northern Europe and in the south (mainly Italy). Roman mythology was

becoming a popular subject for artworks.

The Crucifixion, Anton Woensam (ca. 1540)

The Last Judgment, Jacob de Backer (16th C.)

Venus, Cupid and the Fleeing Envy, Agnolo Bronzino (ca. 1548-50)

Madonna and Child with St. Paul, Titian (16th C.)

The Marriage Feast at Cana, Giorgio Vasari (1566)

Christ on the Cross, Paolo Veronese (ca. 1580)

Hercules Expelling Faun from Omphale's Bed, Jacopo Tintoretto (ca. 1585)

Also represented at the museum is the Brueghel clan of the Habsburg Netherlands.

The first Brueghel to make a name for himself was Pieter the Elder, who is known

for "Where's Waldo?"-like paintings crowded with many small figures. The other

two Brueghels of note were his sons Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder. Pieter

the Younger's style was much like his father's, while Jan was more interested in

developing his own.

The Sermon of St. John the Baptist, Pieter Brueghel the Elder (16th C.)

The Blind Hurdy-Gurdy Player, Pieter Brueghel the Younger (ca. 1600-1610)

Landscape with Animals for Noah's Ark, Jan Brueghel the Elder (ca. 1613-15)

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, Jan Brueghel the Elder (1612-13)

The 17th Century was also a time when Spanish artists were making their mark, and

several of their works are also on display in the museum.

The Agony in the Garden, El Greco (ca. 1610-1614)

Holy Family with St. Anne, El Greco

The Virgin Immaculate, Francisco de Zurbarán (1661)

The Infant Jesus Distributing Bread, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1678)

Some rooms in the museum had both paintings and sculpture.

Hall with Artworks

Bob with Caritas Romana, Giusto le Court (17th C.)

Bust of a Fate, Middle-Italian Master (ca. 1600)

Justice Disarmed, Luca Giordano (ca. 1670)

Flemish/Dutch painting in the 17th Century was largely done for ordinary citizens,

and the subjects were usually portraits or scenes from everyday life.

Portrait of a Married Couple, Anthonis van Dyck (ca. 1617-18)

Arrival of the Boat, Bonaventura Peeters (1637)

River Landscape with Ferry, Salomon van Ruysdael (1644)

A Woman Reading a Letter by a Window, Pieter de Hooch (1664)

Merry Company in a Pergola, Jan Steen (ca. 1670)

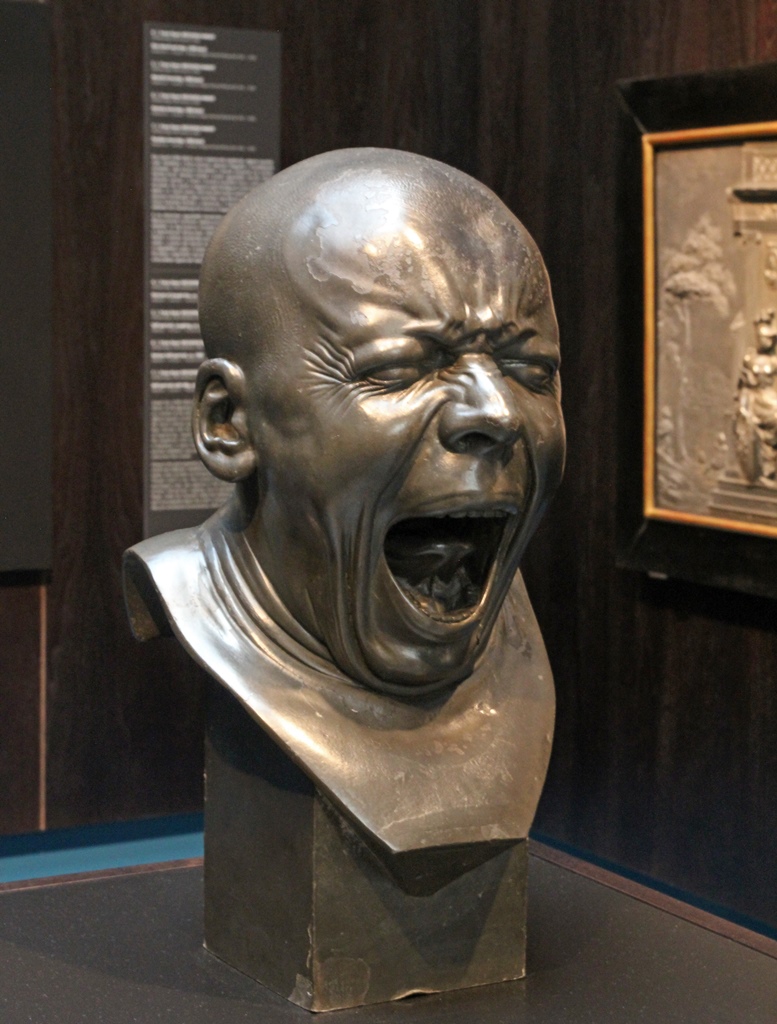

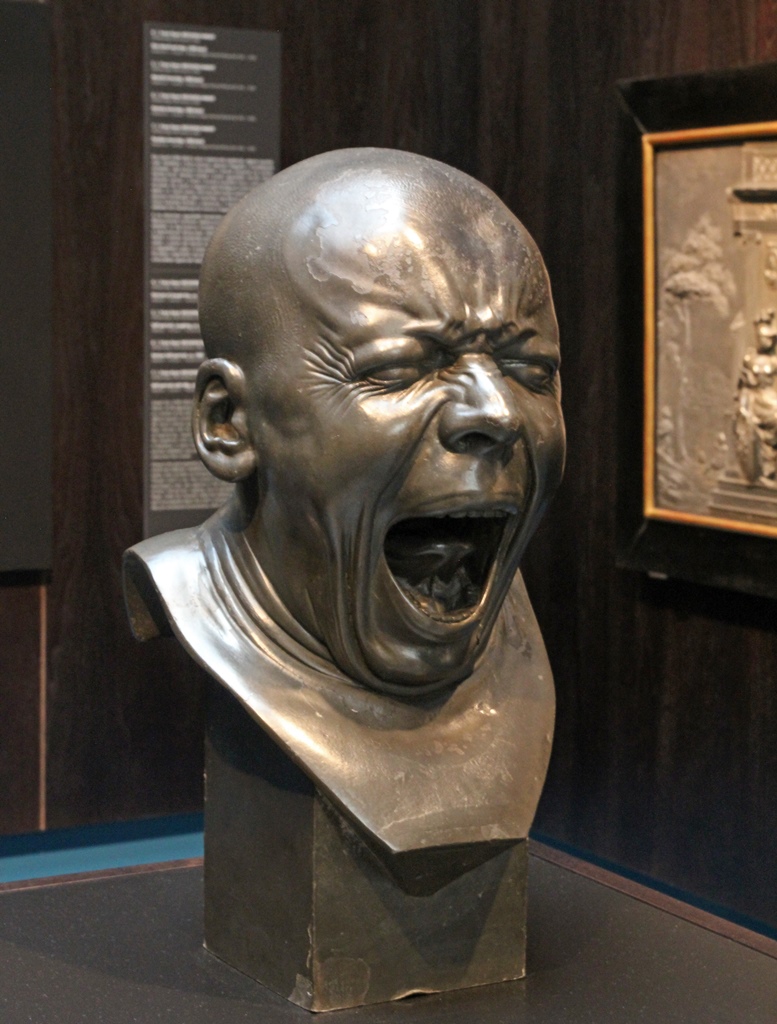

Here are some 18th Century works. Donner and Messerschmidt were German-Austrian

sculptors, and Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) was a Venetian painter, most

famous for his paintings of his hometown.

Judgment of Paris, Georg Raphael Donner (ca. 1735)

The Yawner, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1771-81)

The Piazza della Signoria in Florence, Canaletto (18th C.)

Works from the first half of the 19th Century include the following by the

Spaniard Goya and the Dane Thorvaldsen.

The Knife Grinder, Francisco José de Goya (ca. 1808-12)

Tobias, Bertel Thorvaldsen (1840-44)

Upstairs Gallery

Though Thorvaldsen and Canova would have their supporters, the most celebrated

sculptor of the 19th Century would probably be Auguste Rodin.

The Age of Bronze, Auguste Rodin (1876)

Eternal Springtime, Auguste Rodin (1884)

And no 19th Century collection could be considered complete without some examples

of French Impressionism.

Lady with a Fan, Edouard Manet (1862)

Three Fishing Boats, Claude Monet (1886)

The Black Pigs, Paul Gauguin (1891)

Dining Room at Grand-Lemps, Pierre Bonnard (1899)

Finally, the Swiss artist Arnold Böcklin was a painter of scenes with mythological

figures, influenced by Romanticism. Despite the gravity of most of his paintings (he

painted five different canvases called "Isle of the Dead"), he seems to have harbored

a somewhat goofy sense of humor. His "Centaur at the Village Blacksmith":

Centaur at the Village Blacksmith, Arnold Böcklin (1888)

After combing through the Museum of Fine Arts, we were ready for a break, being

still pretty jet-lagged, so we headed back to the hotel for some rest. But we were

not retiring for the day – we had an appointment for dinner, at which we would be

sampling both the food and the culture of Hungary.