The Great Mosque of Córdoba, built through considerable effort and expense by the Moorish

Umayyad dynasty, has not in fact been used as a mosque since June 30, 1236. It was on this

date that Ferdinand III of Castile took possession of the city, a day after its formal surrender

ended a siege by the Christian forces. One of the first tasks addressed on this day was the

consecration of the celebrated mosque as a Christian cathedral, now formally known as the

Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption. Islamic practices have not been allowed in the

Mezquita ever since, with requests to end this policy having been turned down by the Roman

Catholic Church on more than one occasion. The Catholics' point of view is somewhat

understandable – it's their church, and other religions should practice in their own

facilities (there are functioning mosques in the area). But there are area Muslims who remain

less than content with this situation.

During the Reconquista, the repurposing of mosques as Christian places of worship was a

fairly common practice. The same thing was done in Seville when it was captured twelve years

later. But the Seville mosque/cathedral eventually deteriorated to a point where it had to be

rebuilt, while the bulk of the Córdoba mosque was retained, with the help of appropriate

maintenance. And improvements were made in Córdoba, though of an unmistakably Christian

character. Which we discovered as we wandered through this rather schizophrenic building. Some

were on the subtle side, or architectural in nature.

Philip in Gothic Corridor

Villaviciosa Chapel

Other improvements were more overt. Sprinkled liberally among the Moorish arches are many

altars and Christian accents.

Christian and Moorish Arches

Crucifixion Relief in Moorish Arch

Nella and Altar of St. Christopher

Altar of the Santísimo Cristo del Punto

Altar of Our Lady of the Pillar

Altar of Our Lady of the Sun

Altar of Santa María el Azul and Angel de la Guarda

Altar of San Isidoro, San Leandro and San Ignacio

Another theme consistent with other cathedrals we'd visited was the fact that Catholics

love their chapels. The many chapels of the Mezquita are mainly lined up along the

east, west and north walls of the building. This explains why many of the doors found

on the outside of the building don't go anywhere – there are chapels in the way. As in

many cathedrals, most of the chapels are behind gates, probably to protect them from

tourists who might poke at them. Taking pictures of them between the bars is usually

possible, though.

Chapel of Our Lady of the Conception

Chapel of Our Lady of the Conception, detail

Old Chapel of Our Lady of Conception

Chapel of San Simón and San Judas

Chapel of San Agustín and Santa Eulalia de Mérida

Chapel of Our Lady of the Snows and St. Vincent Martyr

Chapel of San Antón

Chapel of the Holy Trinity

Chapel of San Acacio and Companions

Altar of the Incarnation

Chapel of the Conversion of St. Paul

Ceiling, Chapel of the Conversion of St. Paul

Chapel of Ihesu Verde and San Nicolás de Bari

Chapel of Santa Marina, San Matías and the Baptistery

Chapel of San Juan Bautista

Capilla de Nuestra Señora de la Antigua

Chapel of the Angel of the Guard

Grille, Chapel of the Holy Spirit

Some chapels are more elaborate than others. One such chapel is the Chapel of St. Teresa,

which is actually open to visitors (partly because it's part of the Treasury, discussed

below). This chapel is octagonal, and contains a number of altars and paintings. The

two most prominent works in the chapel are probably the tomb of Cardinal Salazar and the

Monstrance of Arfe. The large tomb is made from both black and white marble and holds the

mortal remains of Cardinal Don Pedro de Salazar, who was Bishop of Córdoba from 1686 until

his death in 1706. During his lifetime he sponsored a hospital and a convent in Córdoba,

and conceived the idea for the chapel in which he is buried, which is also known as the

Chapel of Cardinal Salazar. The Monstrance of Arfe is impossible to miss, as it sits in

the center of the room and is nearly nine feet tall. The Monstrance dates back to 1518,

and no, it wasn't dedicated to someone's dog – it was created by a goldsmith named Enrique

de Arfe.

Chapel of St. Teresa - Salazar Tomb

Monstrance of Arfe

Monstrance of Arfe, detail

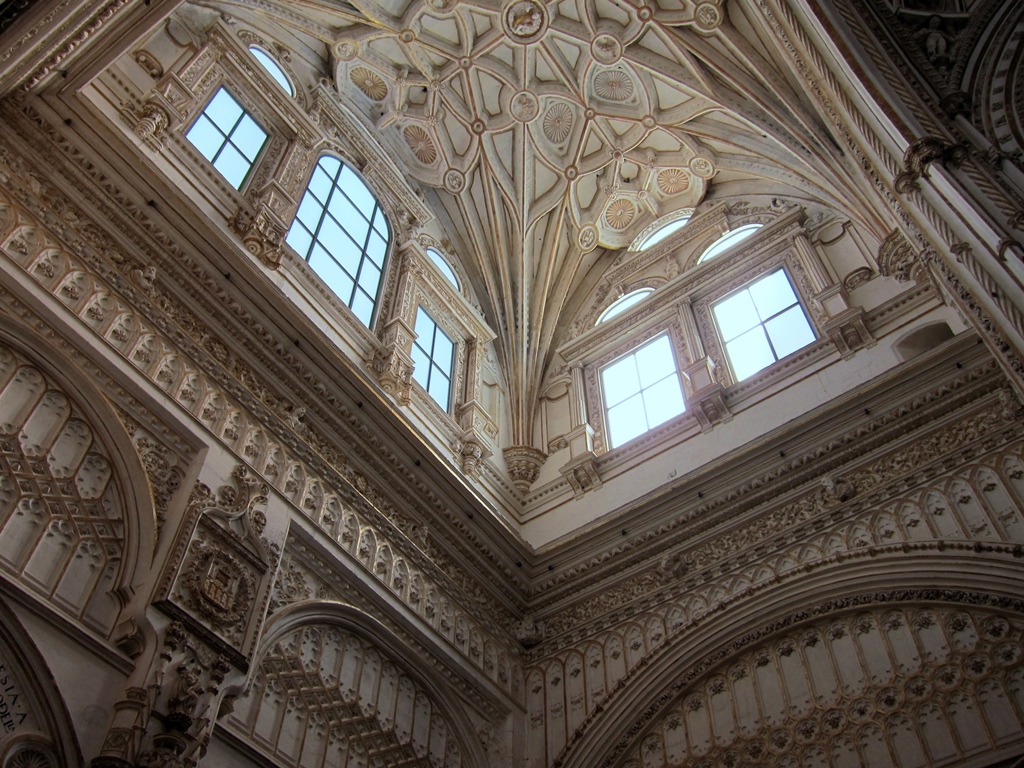

The largest chapel, located in the southeast corner of the Mezquita, is the 16th Century

Chapel of the Tabernacle, which could be a whole church by itself. It has three naves

and several rows of pews, and every square inch of the walls and ceiling appears to be

covered with artwork. We weren't able to get a very close look at any of it, though, as

the gate was locked and we had to peer through the bars. Apparently a number of bishops

are buried in this chapel.

Chapel of the Tabernacle

Chapel of the Tabernacle

Madonna & Child, Chapel of the Tabernacle

Chapel of the Tabernacle

Chapel of the Tabernacle

Another chapel of special significance is the Royal Chapel, which is named for the fact

that it once contained the remains of two kings, Alfonso XI (1311-1350) and Ferdinand IV

(1285-1312). The chapel was built during the reign of Henry II (1334-79), the son of

Alfonso XI (and grandson of Ferdinand IV). For those keeping track, this is the Henry

of Trastámara who gained the throne by stabbing his half-brother Pedro the Cruel to

death (as described in

the page for Seville's Alcázar).

Alfonso and Ferdinand were eventually moved to the Church of San Hipólito, elsewhere in

the city, so the chapel isn't as royal as it used to be. It's not possible to enter this

chapel, but there are openings through which some of it can be seen. The chapel is

decorated in semi-Moorish Mudejar style, and is presided over by a figure of Córdoba

conqueror Ferdinand III.

Royal Chapel

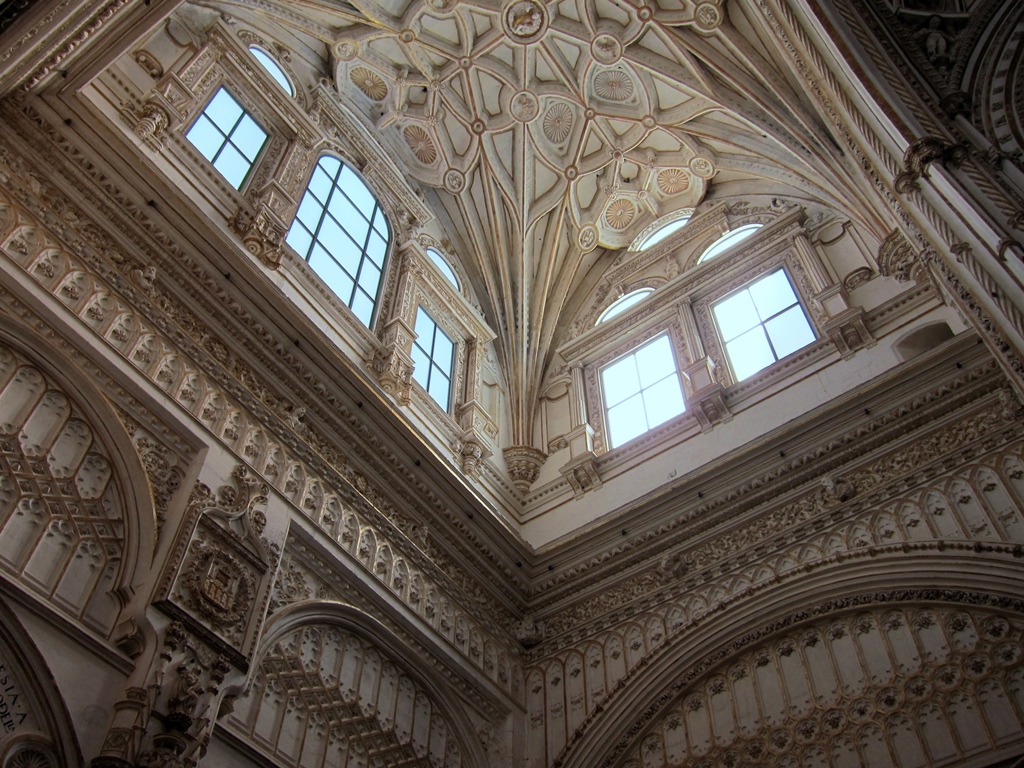

Centuries after the conquest of Córdoba, around 1516, the new bishop of Córdoba, Don

Alonso Manrique de Lara, embarked on a major initiative for the Mezquita. Up until

that point, Christian worship in the building had been centered in a Main Chapel which

was located near its western edge. De Lara felt that the main chapel should be in the

heart of the building, more toward its center. This developed into a major

disagreement between the clerics (many of whom actually disagreed with their bishop)

and the city council, who felt the Main Chapel should be left where it was. Things

became heated, with threats of violence from one faction and of excommunication from

the other going back and forth, until emperor Charles V intervened, telling everyone

to shut up and to let the bishop perform the construction he deemed necessary. The

construction began in 1523 and lasted until 1607, and the result has been called a

"cathedral within a mosque". This "cathedral" (not really an accurate name, as the

whole Mezquita is a cathedral) is visible from the outside as an apparent church

protruding from the top of the otherwise mostly flat building, and on the inside as

a tall, brightly-lit Renaissance church, with no architectural relationship to the

Moorish arch-forest surrounding it. It's said that the emperor revisited in 1526,

after construction was well underway, and expressed regret that he'd green-lighted a

project that "destroyed something unique in the world", and replaced it with

something commonplace (many are skeptical that this really happened, as admitting to

a mistake would have been very out of character for Charles V). But regardless of

one's approval or disapproval of the project, one would have to admit that a cathedral

sprouting from the middle of a mosque is actually pretty unique.

Mezquita with "Cathedral"

Entering the Great Chapel

Great Chapel

Ceiling and Windows

Pulpit and Great Chapel

Great Chapel

Ceiling

Top of Altarpiece

Lamp

Pulpit

Altarpiece "Temple"

Tomb of Bishop Mardones

De Lara didn't get a chance to micromanage the construction of his chapel, as he was

named Archbishop of Seville in 1523, when construction was beginning. This forced

him to relocate - maybe his superiors felt he had worn out his welcome in Córdoba.

But those working on the chapel seem to have done a spectacular job, even without

his help. The entire structure is quite tall and flooded with light (especially

when compared to the dimness of the rest of the Mezquita), with the chapel itself

housing a gigantic marble altarpiece. But the chapel isn't just a chapel. The

structure also has a transept and a nave (with a dome at their intersection),

giving it a Latin cross layout. Beneath the nave is a choir filled with beautifully

carved wooden choir stalls and flanked by two huge dueling pipe organs. But that

seems to be about it – in particular, there is nowhere to put a large congregation

of worshippers, as you would normally have in a cathedral. This makes it difficult

to know exactly what to call this 16th Century insertion into the Mezquita. Maybe

a chapel on steroids.

Ceiling and South Organ

Ceiling

North Organ

Episcopal Throne, Choir

Episcopal Throne, Detail

Choir Stalls, Detail

Cathedral Trascoro and Ceiling

The Mezquita is filled with valuable historical objects, mostly found in the chapels.

But some additional ones are found in the aforementioned Treasury, which includes the

Chapel of St. Teresa. Here are a few:

Treasure Room

Treasure Room - Figure of San Rafael

Ark of Holy Thursday

Processional Cross of Archdeacon Simancas

Bound Liturgical Volumes

Stained Glass

Having had our fill of the Mezquita, we left as we had come in, through a doorway on

the west side of the courtyard. Across the street from the Mezquita we noted a building

with an impressive doorway. This building turned out to be the Palace of Congresses and

Exhibitions, first built as a hospital between 1512 and 1516 on the ruins of the old

Umayyad fortress. Apparently there is an impressive cloister inside, but they seemed to

be closed for the day.

Philip and Palacio de Congresos y Exposiciones

Doorway, Palacio de Congresos y Exposiciones

So we went looking for somewhere to eat dinner. This turned out to be at a place down

the street from the hotel, and turned out to be pretty good if I recall correctly. The

pictures reveal a long, breaded thing with French fries and a plate

stacked with large fried anchovies. While many people like anchovies on their pizza,

Nella likes anchovies on her anchovies, so she must have been thrilled when she saw

this on the menu.

Nella and Bob at Dinner

Philip at Dinner

Breaded Object

Anchovies

After dinner it was finally getting dark outside, so we took a short stroll to see

how well Córdoba did their mood lighting. Pretty well, as it turned out.

Mezquita Bell Tower

Roman Bridge

Puerta del Puente

Returning to the hotel, we unpacked enough to get us through the night. We were

only staying one night – the next morning we would be boarding a train to take

us back northward, to the city of Toledo.