Melk is a town of about 5,300, located about 55 miles west of Vienna. It's

situated near the confluence of the Melk River with the Danube and has a lengthy

history. The Romans had a small fort called Namare at this spot, and there

is evidence of human habitation even before this time, with Stone, Bronze and Iron

Age artifacts having been found on a rocky promontory now located above the town.

This promontory has played an important part (probably the important part) in the

town's history, being home to the immense Melk Abbey, which has occupied the spot

since 1089. While the town is a pleasant and historical place to spend some time,

the abbey (known as Stift Melk to the locals) is the main attraction for

visitors, not just of Melk, but of the entire surrounding area. The many

attractees included us, who got there by taking an hour-long train ride from

Vienna's Westbahnhof.

Melk Train Station

Abbey from Melk

Nella and Abbey

In addition to us and a number of Holy Roman Emperors, well-known visitors to

the Melk Abbey have included Charlemagne, Napoleon Bonaparte (twice), Maria Theresa

(three times) and the author Umberto Eco, who did research for his book The Name

of the Rose in the abbey's library (and gave Melk a mention in the book). But

the abbey wasn't always an abbey. At the time of Charlemagne's visit, in 791, it

was a defensive fortification on a hill, and during the time of the Babenbergs it

was upgraded to a castle and became their headquarters for about 100 years. It

would also become the favorite burial place of the Babenbergs. In 1014 they

decided that the presence of an actual saint would make the castle a suitable

burial place. All the saints of old were already spoken for, so they opted for St.

Coloman, an Irish pilgrim who had recently been martyred in Stockerau (in

northeastern Austria), in 1012. The saint's remains were brought to Melk and

buried in the castle church. Over the next hundred years, Coloman was joined by a

succession of deceased Babenbergs. Then around 1040, the Babenbergs acquired a

splinter of the true cross and had this sent to the castle as well, where it was

encased in a jeweled gold container that came to be known as the Melk Cross. By

1089, Austria had expanded enough that Melk was no longer of value as a frontier

fortification, and the presence of the saint and the Melk Cross led to a decision

to transition the castle to fully religious purposes. This was accomplished when

Leopold II turned the castle over to the Benedictine monks of Lambach Abbey,

located about 80 miles to the west, who sent over a contingent to take possession.

Benedictine monks have been present at the abbey, performing their monastic duties,

from then to the present day.

Over the centuries the abbey has had its ups and downs, among them periods of poor

harvests (the abbey's principal funding came from agriculture on lands that it

owned), the transition from Babenberg rule to Habsburg rule, and a catastrophic

fire in 1297 which forced the rebuilding of the abbey's church and library. But

despite all their problems, the abbey rose to become the most culturally and

spiritually influential abbey in the region, with its influence extending well

beyond the boundaries of Austria. The Reformation, though, was not kind to the

abbey. Protestantism proved to be attractive to many in Austria, and the monastic

population dwindled until only a few monks remained. But the abbey was saved by

an influx of new blood from southern Germany toward the end of the 16th Century.

In 1700, new Abbott Berthold Dietmayr proposed a renovation of the church and a

sacristy, as the high chancel was in danger of collapsing. The project was

approved for obvious reasons, and work began in 1701. Shortly after the start of

work, in a sequence of events familiar to many who've had the experience of

replacing a bathroom towel rack, someone said, "Maybe we can just rebuild the whole

church!" There was a little more pushback on this proposal, but it was ultimately

approved as well, with resulting increases to the cost and the schedule. Ten years

later, in a pronouncement that may sound familiar to some of those who have dealt

with contractors, someone said, "The new church is heavy baroque and doesn't match

anything else! We're gonna have to redo the whole abbey complex!" As should

probably be expected, there was considerable resistance to this idea, and formal

complaints were lodged with both the emperor and the papal nuncio. But the plan

was upheld by both parties, and work on the abbey continued until 1736, when the

now elderly Abbott Dietmayr could anticipate the completion of the work. At this

point there was another catastrophic fire, this one destroying the roofs and

several rooms. Dietmayr groaned and authorized the necessary repairs, but did not

live to see their completion. The repairs were not simple, but they were

eventually completed, and the new church was consecrated in 1746. The abbey at

this point was essentially the one that is seen today.

Model of Town and Abbey, ca. 1701

Model of Present-Day Abbey

The abbey survived through World War I reasonably well, but it came through the war

badly in need of renovation work. With the post-war economy being horrible, these

renovations were financed through the sale of some of the abbey's cultural

possessions, such as its Gutenberg Bible, which was sold in 1925 (it's now owned by

Yale University's Beinecke Library). World War II brought additional challenges.

After the Anschluss with Germany in 1938, most of the abbey was taken over

by the state and used as a school. The monks, however, were allowed to continue

practicing in a small corner of the abbey. The town of Melk was enlisted into the

Nazi cause, with a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp being installed

there. Mauthausen and its subcamps were originally devoted mainly to political

prisoners, who were systematically worked to death. As the war continued, the

varieties of prisoners admitted to the camp increased, as did the varieties of

methods by which they were exterminated. Toward the end of the war, the Melk

subcamp held approximately 10,000 inmates, making it the fourth most populated

subcamp. The site of the subcamp is now a museum (housed in the subcamp's former

crematorium) and a barracks center for the Austrian Army.

The abbey has largely returned to its original monastic purposes, but a

considerably larger source of funds has been added to its traditional sources of

income (agriculture and logging), in the form of tickets sold to visiting

tourists (like us).

Getting to the abbey from the train station took a little walking, but since the

abbey is such a gigantic landmark, getting totally lost was not really possible.

Heading toward the abbey from the station took us down into the town center, and

signs posted there took us to a stairway that led up the hill, leading us to the

abbey's main entrance, where 1716 statues of St. Leopold and St. Coloman welcome

visitors.

Bob on Stairway to Abbey

Nella and Abbey Front Gate

Entering through the portal took us into a courtyard called the Gatekeeper's

Courtyard. The ticket office is found in this courtyard, and to the far right

one can see a white, cylindrical tower which is one of the few abbey structures

that date back to the Babenberg version of the abbey. But straight ahead there

is a large building with another portal leading through it. This is the outer

wall of the actual abbey, and the doorway into it.

Bob and Abbey's Eastern Façade

Eastern Façade detail

Passing through the doorway leads into another courtyard, surrounded by walls

and windows and home to a smallish fountain. This is the Prelate's Courtyard.

The dome of the abbey church can be seen protruding above the western face of

this courtyard. Small modern frescoes can be seen at the top of all four

surrounding walls of the courtyard. These frescoes were added between 1988

and 1990 by artist Peter Bischof and represent the four cardinal virtues

(prudence, temperance, justice and fortitude). The fountain was brought in

from another monastery in the early 19th Century to replace another fountain

which had been given to the city of Melk during the 18th Century rebuild

(this fountain is now in front of the town hall).

Prelate's Courtyard

Church Dome and Prudence Fresco

Fountain, Prelate's Courtyard

Bob in Prelate's Courtyard

Clock and Justice Fresco

In the southwestern corner of the Prelate's Courtyard there is a small archway

which leads to a walkway between the church (on the right) and some rooms on

the left. We'll get to the church, but first we took a left turn to visit what

were once called the Imperial Rooms, but which are now the exhibition rooms of

the abbey's museum. The rooms are upstairs, and are reached via the Imperial

Staircase.

Walkway Between Museum and Church

Imperial Staircase

Statue, Imperial Staircase

There is a long corridor parallel to the museum rooms which features several

portraits of the Austrian royal family. We weren't too interested in these,

as we were more focused on the museum itself, but here's a portrait of Maria

Theresa.

Maria Theresa as Queen of Hungary (ca. 1741)

On display in the museum are many small objects, the most valuable of which

is probably the 14th Century Melk Cross. The original Melk Cross was created

in the 11th Century to hold a splinter of the true cross, as described above,

and is not normally displayed. This version was commissioned by Duke Rudolph

IV in 1362.

The Melk Cross (1362)

The Melk Cross (1362)

Here are some more of the objects displayed in the museum. The Coloman

Monstrance was built to contain the lower jawbone of St. Coloman. Ulrich's

Cup was originally fashioned from a squash peel and is thought to have been

used by St. Ulrich in the 11th Century. The silver lining was added in the

14th Century.

Coloman Monstrance, Joseph Moser (1752)

Ulrich's Cup (mid-14th Century)

Relic Cross (ca. 1510-20)

Crucifix (ca. 1200)

More items were found in a room with mirrored walls:

Room of Goblets and Monstrances

Gilded Figure of St. Anne

A Chalice

A Chalice

Monstrance, Polish (ca. 1780)

Treasure Chest and Locking Mechanism (17th C.)

There are also vestments on display:

A Miter

Crozier

Berthold Vestments

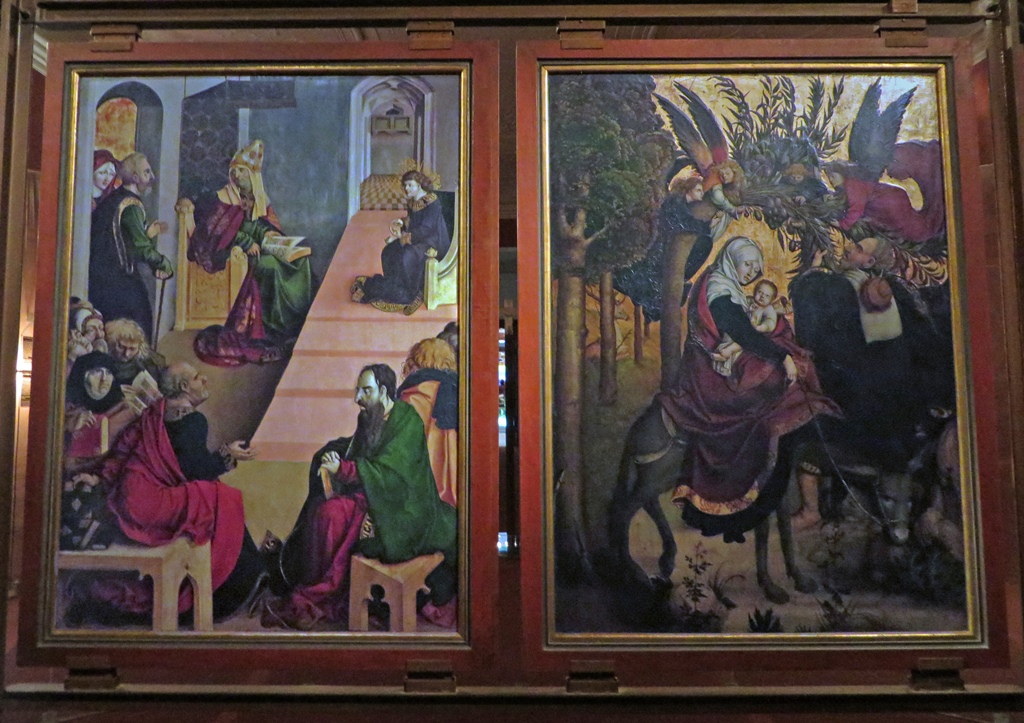

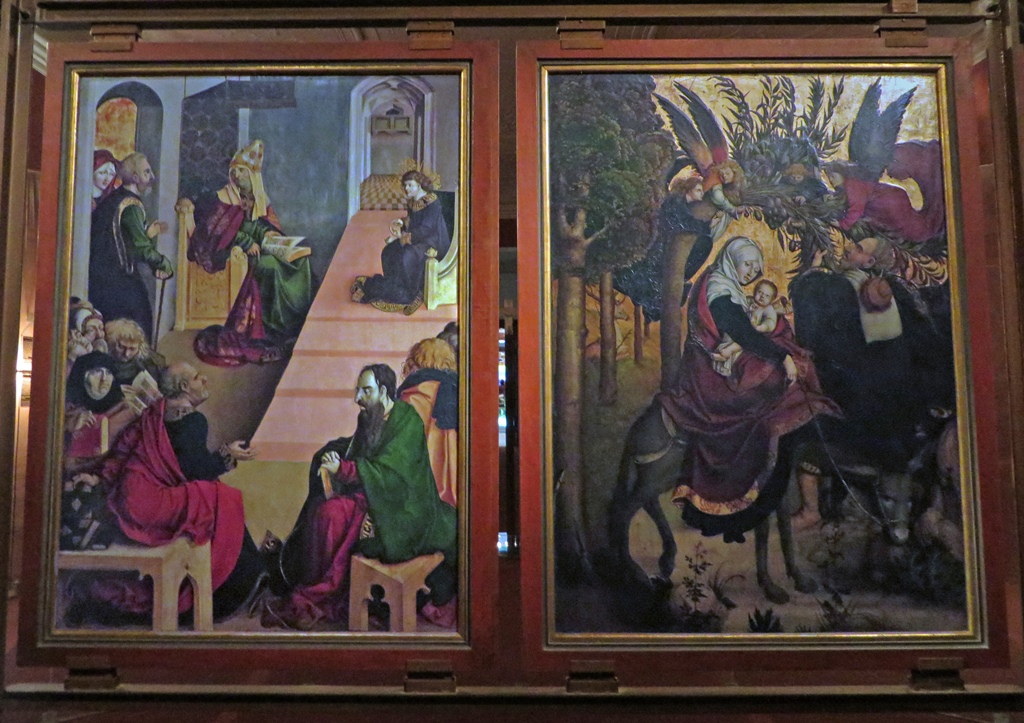

Another room is devoted to the Breu Altar, a winged altarpiece with sixteen

panels (eight on the front, eight on the back), created in 1502 by Jörg Breu

the Elder. Here are some of the panels:

Breu Altar (front side), Jörg Breu the Elder (1502)

Christ on Mount of Olives and Scourging of Christ

Breu Altar (back) - St. Paul and St. Florian

Jesus in the Temple and The Flight to Egypt

Leaving the museum, the visitor route leads to a large, thoroughly baroque

room called the Marble Hall. It was used for festive occasions, particularly

those involving the Imperial court. I'm not sure if they rent it out (e.g.

weddings, graduations, frat parties, bar mitzvahs; well, probably not bar

mitzvahs), but it would certainly be a cool place for a party. The name of

the room is something of an exaggeration – the only real marble is around the

entrance and exit doors; anything else that looks like marble is simulated.

The allegorical ceiling fresco was done by Paul Troger in 1731 and has a lot

going on.

Marble Hall

Bob in Marble Hall

Marble Hall Ceiling Fresco - Paul Troger (1731)

Marble Hall

Above Doorway, Marble Hall

From the Marble Hall we were routed to a terrace, from which there were

splendid views of Melk and the valley in which it's situated, and of the

façade of the abbey church.

Church Façade from Balcony

Church Towers with Christ Statue

Church Façade (detail)

Melk from Balcony

Melk River with Bridge

Melk River Connection to Danube River

Following the terrace, we were routed back indoors, into the abbey library. The

library is also amazing to look at, and houses many thousands of invaluable

volumes, but unfortunately photography was not allowed in the library. Here's a

public domain picture off the Internet:

Melk Library

From the library a stairway led us down into the main attraction, the abbey

church. The church can only be described as over-the-top baroque, with a

special emphasis on gold.

The Church

The Church

Looking at some of the common elements of Catholic churches, we began by

looking at the main altar, which is anything but common. The altar was designed

by Giuseppe Galli Bibiena, and is quite complex, being covered with life-sized

figures of saints, prophets and angels, surrounding an immense crown of victory.

This is mostly done in gilded wood, but there is also marble (which is not

simulated).

Main Altar

Crown of Victory, Angels, God with Moses and Aaron

Main Altar

Choir Stalls

At either end of the transept there are two large altars, devoted to St. Benedict

(this being a Benedictine abbey) and St. Coloman (this being the Melk abbey).

Both altars have sarcophagi, but the one in the St. Benedict altar is empty

(Benedict is buried in Italy). The St. Coloman sarcophagus, however, contains

the venerated remains of the saint himself.

St. Coloman Altar

St. Coloman's Sarcophagus

St. Benedict Altar

The dome, situated above the intersection of nave and transept, contains a

fresco (by Johann Michael Rottmayr) that is crowded with figures which are

difficult to pick out from ground level. Apparently there are the Father,

Son and Holy Spirit, plus Mary, the apostles, a host of saints and even a

heavenly version of Jerusalem. And this doesn't even include the ceiling

figures that surround the dome.

Dome

Shell Pattern, Base of Dome

The fresco above the nave, also by Rottmayr, is a multi-paneled depiction of the

ascension of St. Benedict to heaven.

Ceiling Fresco - "The Triumph of St. Benedict"

Returning to ground level (almost), the pulpit, also designed by Galli Bibiena,

apparently depicts the casting of demons of unbelief into the depths (of Hell,

no doubt).

Pulpit

In the back of the church there is an organ that was built in 1970. It has

three keyboards, 45 stops and 3553 pipes. It's up in the choir, and

underneath the choir there is yet another fresco.

Organ, Ceiling and Side Chapels

Organ

Fresco Under Choir

Along the sides of the nave, as in many Catholic churches, there are side

chapels, and above the chapels there are several balconies.

Balcony

Balconies

Side Chapels and Balconies

Side Chapels and Balconies

There are only six side chapels (three on each side), but they are well worth a

look. Two of them feature lavishly bejeweled skeletons, both of them anonymous

"catacomb saints" (from under the Stephansdom in Vienna?). But they have been

given names by the monks of Stift Melk – the skeleton of St. John the Baptist's

altar has been called "Friedrich", and the skeleton of St. Michael's altar has

received the name "Clemens". Both were gifts (something special for the abbott

who has everything?) – Clemens came from the Viennese nuncio in 1722, and

Friedrich was donated by Maria Theresa in 1762.

St. Sebastian's Altar (Troger, 1746)

St. Nicolas's Altar (Troger, 1746)

Epiphany Altar (Rottmayr, 1723)

St. John the Baptist's Altar (Rottmayr, 1727)

St. Michael's Altar (Rottmayr, 1723)

St. Leopold's Altar (Bachmann, 1650)

Having seen enough of the church, this concluded our visit to the Abbey of Melk,

and we returned back down the stairs up which we had come. We found a late

lunch in town, and we returned to the train station for our trip back to Vienna.

Nella and Archway on Stairs Back to Town

Bob and Orange Soda

Nella and Orange Soda

Melk Train Station

On returning to our hotel, we took some time to rest and to begin packing.

This was to be our last evening in Vienna. Maybe we should have commemorated

the evening by eating something distinctly Viennese, but we weren't that

ambitious, ending up at McDonald's instead. But we did take the time to walk

around among some of Vienna's landmarks one last time (until our next visit!).

Dinner at McDonald's

Stephansplatz

Graben

Pestsäule

Peterskirche

We returned to our hotel on Tiefer Graben, noting the Wipplingerstrasse

overpass which had confused our taxi driver on our arrival (on a map, it

looks like an intersection).

Nella and Wipplingerstrasse Overpass

Hotel das Tigra and Tiefer Graben

We packed what we could and went to bed in anticipation of the journey we

would be taking the following day. Another day, another country (or

another two countries, as it would turn out). Our plan? Zürich,

Switzerland.